The Novel and the Author

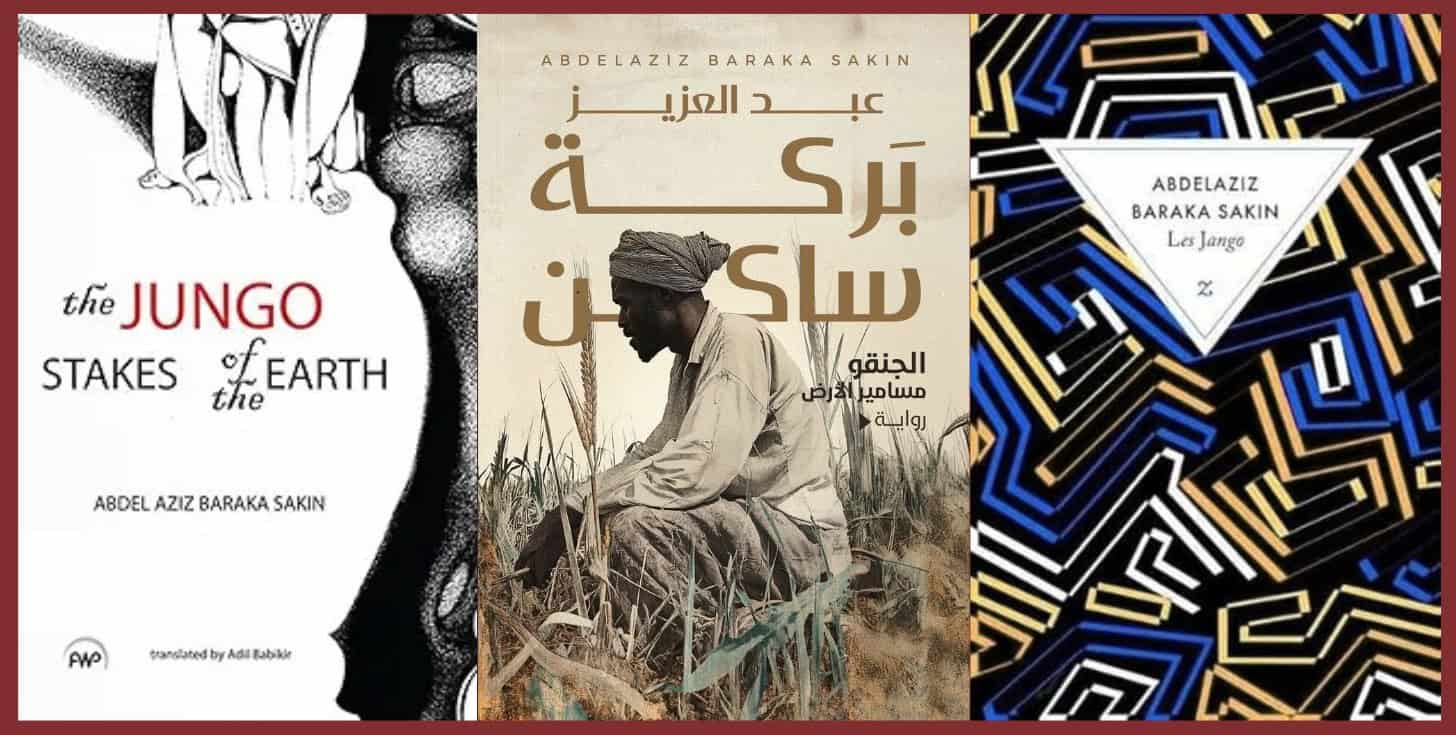

The novelist Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin, widely regarded as one of the most prolific and internationally acclaimed Sudanese writers, achieved broad recognition with his novel The Jungo: Stakes of the Earth (2009) (الجنقو – مسامير الأرض), which has been widely read and translated into several foreign languages because of its thematically controversial content. The novel exposes unspoken and suppressed social fractures within Sudanese society and powerfully destabilizes entrenched moral and political certainties by addressing thorny issues of marginalization, sexuality, political polarization, and social consolidation.

The word Jungo is originally derived from Jungora, referring to people from western Sudan who migrated eastward to work in agricultural projects. The word also carries an implicit derogatory connotation, suggesting worthlessness or social inferiority. Etymologically, it is associated with torn or ragged garments, a description that came to be applied to these seasonal socially non-engaged people because of their harsh working conditions and rugged appearance.

First published in 2009, the novel won the prestigious al-Tayeb Saleh Award, marking a significant moment in the author’s literary career. Set within the paradoxical reality of agricultural workers, The Jungo: Stakes of the Earth traces the dire behavioral and daily lives of those deprived of their rights within their own state. It provides an account of an unbearable existence within Sudanese social and economic relations that are astoundingly similar to the age of feudalism and enslavement.

By no means a manifesto of workers’ rights, the novel is instead rich in vivid narrative imagery that encapsulates the nuanced life of a particular community and its struggle within the interactive contexts through which it is socially and economically defined—and continually redefined. Moreover, it does not foreground racial tensions beyond those embedded in economic and labor relations: the divide between Jungo (workers) and Jalaba (owners), between those who have and those who do not, a social structure in which discrimination undeniably exists. This is a sphere of life in which human obsessions surface only faintly, expressed through varied and unsettled existential responses.

As the novel seeks to incorporate, both narratively and logically, the processes through which such a social unit has been formed and fermented, these dynamics permeate its characters, charting a realist story populated by men and women of tangible, lived presence—figures driven by both moral and immoral impulses alike. The narrative structure, underpinned by an array of seemingly ordinary fictional characters, is powerfully dominated by an omniscient narrator who guides events while allowing the participation of key figures such as Wad Amona and al-Safia the eccentric heterosexual, jailers, wine sellers, religious charlatans, and others.

Among the many figures in the narrative, Alem Gashie emerges as the character closest to the narrator. Their dramatic relationship, unfolding across the novel, powerfully reveals a profound human connection that transcends race, religion, and entrenched social boundaries. Although she occupies a prominent position within the evolving plot, the author simultaneously insists on a decentralized narrative structure. Rather than privileging a single protagonist, the narrative allows every character—including Alem Gashie—to participate meaningfully in shaping the novel’s overall form and vision.

Together, these characters not only endow the text with rich narrative vitality, but also construct a mosaic of folkloric, anthropological portrayals of marginalized lives and their unfulfilled dreams.

Through its translation into English by Adel Babikr and into French by Belgian Xavier Luffin, the novel has captured the focus of international journalism. This global visibility led to significant honors, including the 2020 Prix de la Littérature Arabe and Baraka’s 2023 appointment as a Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters (Ordre des Arts et des Lettres) by the French Ministry of Culture.

Remarkably, this novel elevated its author to an iconic status among Sudanese writers and secured him wide recognition beyond Sudan, where he has been widely celebrated by readers, critics, and international audiences. Yet this very success also marks a decisive shift in the political life of the text. More broadly, the novel’s title has entered everyday Sudanese discourse, circulating even among those who may never have engaged with the work itself. The term Jungo has thus detached itself from its dense narrative and socio-historical context to become a floating signifier in popular speech, designating in a simplified manner the rugged world of Sudanese lower-class labor.

In this process of popularization, the novel’s critical force is both extended and partially neutralized. On the one hand, Jungo gains unprecedented visibility as a symbol of marginality and exclusion; on the other, its transformation into a colloquial label risks emptying it of its analytical depth, reducing a complex social formation to a cliché of poverty and roughness. What circulates socially is no longer the novel’s sustained critique of economic relations, racial hierarchies, and structural injustice, but a condensed emblem that can be easily appropriated, sentimentalized, or even depoliticized.

In this sense, the novel’s success participates in a paradox of cultural recognition: the very mechanisms that canonize a work of resistance may also domesticate it. By turning Jungo into a popular metaphor, public discourse converts a narratively constructed site of protest into a manageable cultural token, one that signals awareness of marginality while potentially displacing the more unsettling questions the novel originally posed about power, class, and the historical production of exclusion

Since its publication, the work has generated intense controversy. It was banned by the former Sudanese regime, which condemned it for violating social taboos and exposing what it considered moral “obscenity” and politically unwelcome truths. In reality, the ban reflected the regime’s anxiety toward a narrative that laid bare the hidden violence, exclusions, and hypocrisies embedded in the social and political order. In this sense, Jungo stands as both a literary and political intervention, revealing how fiction can become a site of resistance against censorship and authoritarian control.

For the most part, the rejection of the novel’s content has stemmed from religious, moral, and cultural backgrounds that claim purity and the preservation of social tradition. The objections raised are closely linked to the novel’s thematic concerns, particularly its portrayal of characters who are narrated within their lived social realities rather than idealized or morally sanitized representations. At times—if not consistently—the narrative foregrounds reality in defiance of dominant dogmatic public discourse.

In this respect, Jungo is not exceptional. In al-Tayeb Ṣaliḥ’s Season of Migration to the North, the village setting similarly includes frank and sensitive sexual descriptions, most notably in the stories of Bint Majzoub, along with other elements that may be socially interpreted as immoral. Such narrative strategies underscore a broader literary commitment to representing lived experience, even when it unsettles prevailing moral norms.

Among Baraka Sakin’s other narrative works, particularly Messiah of Darfur, the novelist turns to a subject that had long remained aesthetically underrepresented in Sudanese fiction. In this novel, he addresses the world of the Jungo—a group of seasonal laborers who belong to socially stigmatized and hierarchically degraded tribes, often described in public stereotypes as non-Sudanese, non-Arab, or even semi-slave populations. Originating from regions politically and geographically classified as marginalized, especially in western Sudan and other peripheral areas, the Jungo occupy a liminal social space defined by exclusion and invisibility.

Narrative and Critical Scope

Realistically, Sudan’s marginalized groups consist of a wide array of social classes and communities, including many who remain sociologically invisible and rarely incorporated into any formal classification. These include street children (shamasha), the disabled, the homeless, beggars, and other neglected groups that fall outside both political representation and scholarly categorization. What Baraka Sakin has achieved narratively is not the depiction of marginalization as an abstract political category, but the realistic documentation of a specific community of seasonal workers whose lived condition reflects a constellation of unresolved social crises. Through this focused portrayal, the novel opens onto a plurality of silenced issues that have long fueled heated debate within Sudan’s restless political and cultural discourse.

Perhaps the most compelling comparison to be drawn in this regard lies in the urgent passion of Baraka Sakin’s writing and its unselfconscious intensity, despite the gravity of its critical subject matter. There is an eloquence in this prose that resonates across his broader narrative project, binding The Jungo to his other works through a shared ethical and aesthetic commitment. Through a painstaking exploration of multiple social strata within the wretched world of the Jungo, the novel unfolds with a distinctive narrative force that is both expansive and precise.

In this sense, The Jungo emerges as a lucid epic of documentary fiction, one in which the novelist rises to chart the vast, rolling tides of Sudanese society while simultaneously descending into the minute details of inner consciousness and everyday life. This dual movement—between the collective and the intimate—is executed with equal and remarkable mastery, affirming Baraka Sakin’s ability to render social totality without sacrificing the texture of lived experience.

The novel offers a powerful critical portrayal of their precarious and fragmented lives, depicting with remarkable narrative intensity their vulnerability, their predetermined social fate, and a wretched existence that often culminates only in death. Through this representation, Baraka Sakin not only humanizes a silenced social group but also exposes the structural violence rooted in Sudan’s social hierarchy.

Like Fanon’s colonized subject in his The Wretched of the Earth, the Jungo inhabit a world in which labor does not lead to dignity, mobility, or political incorporation, but only to the endless reproduction of dispossession. Their seasonal movement, economic replaceability, and proximity to death embody what Fanon described as the colonial economy’s most violent truth: a system that lives by exhausting human bodies while denying them historical agency.

Yet Baraka Sakin departs from Fanon in a crucial way. Whereas Fanon’s revolutionary horizon culminates in the possibility of redemptive violence and collective liberation, Jungo suspends such teleology. The novel offers no cathartic rupture, no revolutionary subject in formation, only a slow accumulation of wasted lives. This narrative choice radicalizes Fanon’s diagnosis by stripping it of its eschatological hope: domination here is not a prelude to liberation but a closed circuit of social death. In doing so, Jungo transforms Fanon’s political anthropology into a tragic realism, where the “wretched of the earth” are not on the threshold of history, but trapped in its blind trajectory.

Background of the Sudanese Narrative of Marginalization

A pioneering moment in the history of the Sudanese novel can be traced back to the early 1960s with Khalil Abdullah al-Haj’s They Are Mankind, a work that broke decisively with prevailing literary conventions by bringing into representation a “blind” social category drawn from the underground worlds of a Sudanese city alley. Historically, the novel has been regarded not only as one of the earliest published Sudanese novels, but also as a foundational experiment in social realism, inaugurating a narrative attention to marginal lives that had previously remained outside the literary realm.

Since then, and particularly during the boom of Sudanese fiction in the 1990s, an expanding body of narrative works has continued to revisit and rework these social zones of exclusion. Novels such as Rania Mamoun’s Son of the Sun, Imad al-Balak’s Garsila, and others testify to a sustained engagement with the fractured social fabric of Sudanese society. What emerges across this tradition is not a sporadic interest in marginality, but the gradual formation of a novelistic discourse that has persistently confronted the contradictions, hierarchies, and hidden social and political of Sudanese life.

In this sense, the Sudanese novel has developed less as an autonomous aesthetic project than as a sustained critical practice, one that situates narrative form at the intersection of social inquiry and historical diagnosis. The continuity between al-Haj’s early realism and the later experimental fictions of the 1990s suggests that the concern with society and its complexities is not an episodic theme, but a constitutive trait of the Sudanese novelistic tradition itself.

Yet Jungo is not an isolated case. Other Sudanese novelists, such as Mansour El-Souwaim in The Memory of a Bad Boy, similarly centered marginalized figures and historically excluded communities. More recently, a new generation of Sudanese novelists has revisited the country’s social history with a renewed critical sensibility. Their writing does not merely seek to enrich the pleasures of narrative but to experiment boldly with new literary techniques that break away from traditional modes of representation. Through this audacious turn, they attempt to penetrate the darkest layers of social reality, not to escape it, but to confront it with unprecedented narrative honesty.

Despite the fact that Jungo achieves a remarkable narrative climax by elevating the worlds of the socially lowest strata with exceptional skill—through a carefully constructed novelistic architecture centered on targeted characters and emblematic events—it also opens a wide field of unresolved questions, both literary and political. In doing so, the novel does not merely represent marginal lives, but transforms them into a space of dialogue, interrogation, and critical unease, where narrative achievement and political controversy remain inseparably intertwined.

From a theoretical and critical perspective, the novel invites a reading that resonates with the Marxist tradition and, more specifically, with Georg Lukács’s conception of realism. In Lukács’s understanding, the realist novel does not propagate ideology directly, but reveals the objective structures of social life through the concrete destinies of ordinary characters embedded in determinate relations of production. In this sense, the Jungo approaches what Lukács called the representation of “typical characters in typical circumstances,” where individual suffering becomes a window onto the totality of social relations.

While the narrative can be read analogously to Marx’s analysis of the mode of production and exploitation, it resists becoming an ideological novel. Instead, it remains faithful to the realist vocation of unveiling how economic structures silently govern everyday existence. Human suffering and existential vulnerability thus replace doctrine as the central organizing principles of the narrative, aligning the novel with a critical realism that exposes social truth not through slogans, but through lived experience.

Clash of visions

As Jungo provoked a wide spectrum of critical debates and public reactions, many of these responses remained strikingly detached from any serious literary or critical hypothesis. Rejection, where it emerged, was largely articulated in moralistic terms, expressing less an aesthetic objection than the repressive desires of a society structurally deprived of basic human freedoms. In this sense, the controversy surrounding the novel reveals more about the anxieties and pathologies of the social order than about the text itself. The novel’s unsettling power lies precisely in its refusal to mediate reality according to the expectations of dominant moral and political discourses; it offers, instead, a translation of social life as it is lived, not as ruling groups would wish it to appear.

The official response followed a familiar pattern. The authorities classified the novel as a subversive attack on state policy, particularly on its eco-agricultural arrangements that systematically favored large landowners and entrenched economic interests. This political reading was then deliberately fused with ethnic and social anxieties embedded in Sudan’s fragile social fabric. The result was a campaign of repression: the banning of the novel and the harassment of its author. Paradoxically, these coercive measures did not silence the novel but amplified its symbolic narratives. The state’s attempt to suppress Jungo confirmed its status as a politically dangerous narrative and, in doing so, transformed the novel itself into a public indictment of the very power structures it sought to expose.

What has brought Jungo back into the center of critical attention is not only its intrinsic literary power, but the violent historical conjuncture through which it is now being reread. The current bloody conflict in Sudan has retrospectively charged the novel with a new and unstable political meaning, as if the text itself were anticipating the present catastrophe. This retrospective appropriation has been further complicated by Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin’s own public positioning. His unequivocal condemnation of the war, articulated in a series of widely circulated statements, has paradoxically been interpreted by some as a tacit alignment with the government’s narrative of “necessary war” rather than an advocacy of sustainable peace. In this polarized context, the writer’s moral voice has become politically legible, no longer as an autonomous ethical stance but as a sign to be absorbed into the logic of wartime alignment.

This instrumentalization becomes even more visible when Jungo is read alongside The Messiah of Darfur. In that earlier novel, Baraka Sakin anatomized the Janjaweed as an eccentric, identity-less community driven toward sabotage and destruction, a representation that was originally celebrated as a daring exposure of a hidden social pathology. Yet under the conditions of the present war, this narrative image is increasingly mobilized as retrospective “evidence,” invested with a quasi-prophetic authority that appears to confirm and even legitimize the state’s discourse of extermination. What was once a critical demystification of violence risks being converted into a justificatory archive: a narrative repertoire through which not only armed actors but entire social roots are rendered eliminable.

Context and Narrative Discourse

In this sense, the contemporary rereading of Jungo reveals a decisive shift in the politics of literature itself. The novel no longer circulates merely as a critique of marginalization, but as a text exposed to what might be called wartime hermeneutics, a regime of interpretation in which literary representation is subordinated to strategies of moral authorization. The danger here is not misreading in the narrow sense, but the transformation of critical literature into an alibi for sovereign violence: a process by which narrative, stripped of its ethical ambiguity, becomes a tool in the management of death.

Indeed, the novel has received the critical recognition it deserves within established methodological and theoretical frameworks. Its early reception was largely governed by literary criteria: narrative technique, thematic audacity, and its contribution to the representation of marginality in Sudanese fiction. Yet beyond this institutional critical realm, another kind of effect has gradually been taking shape—an effect that belongs not to criticism but to the unstable domain of political reception and public controversy.

The current devastating internal conflict in Sudan, in which long-standing doctrines, loyalties, and moral certainties have been violently shaken, has drawn Jungo into a new field of debate. In this polarized atmosphere, the novel is no longer read primarily as a literary intervention but as a politically charged document, inseparable from the controversial public positioning of its author and from the fragmented alignments of Sudanese intellectuals themselves. What is at stake here is not merely a disagreement over interpretation, but the transformation of the novel into a symbolic site where the crisis of the intelligentsia is being played out: a space in which literature is compelled to carry the burden of political adjudication.

In this sense, Jungo now circulates between two regimes of meaning: one governed by critical methodology, and another by the urgencies of war, suspicion, and ideological fracture. The tension between these two regimes marks the novel’s present condition and defines the limits of any purely aesthetic reading under conditions of civil catastrophe.

The novelistic form does not merely yield to the empirical; instead, it mediates reality via a dialectic that may diverge significantly from the author’s conceptual framework. Consequently, the author bears no responsibility for subsequent hermeneutics—whether the text reinforces ethical boundaries or destabilizes the “favored orientations” of the public psyche.

Political Misinterpretation

When it comes to Baraka Sakin’s narrative works, which have often been described as combining realist and surrealist modes in both characterization and narrative structure, to read them primarily through the lens of his presumed position for or against war propaganda constitutes an analytically flawed judgment. Such a reading collapses the distinction between the aesthetic logic of the text and the contingent political positioning of the author, and in doing so reduces literature to a mere extension of political allegiance.

Although the novel does not politically articulate the misery of the Jungo, it nonetheless opposes authority through multiple modes of critique. It exposes the hypocrisy of an authority that adopts and perpetuates dominant cultural and economic biases rooted in racialized and discriminatory frameworks. Ultimately, the Jungo are socially and economically confined to predetermined paths, within which they are perpetually treated and classified as a fixed working class.

In other words, although it is impossible to detach any writer entirely from the historical and moral horizon within which he writes, it is equally untenable to subordinate the literary work to a single political standard of loyalty or betrayal. The writer’s expressive texts do indeed convey a humanistic vision through the resources of narrative imagination, but this does not license their retroactive conversion into political statements in the narrow sense. Traditionally, and precisely in critical theory, writers have been understood as exercising a form of soft power against the hard power of authority: a symbolic and ethical intervention that resists coercion not through alignment, but through ambiguity, complexity, and the unsettling of dominant certainties.

Political engagement cannot be entirely evaded, as the novel addresses issues deeply shaped by social and economic strain. Although the Jungo are not politically organized within formal political entities, they nonetheless appear as a potential site of political consolidation. Political constellations are implicitly present through multiple references: the armed rebellion of the Jungo, mentions of Sudanese rebel movements, and the maneuverings of politicians, among others.

At the level of narrative construction, the novel’s settings are immersed in political circumstances that have produced a form of social enclosure—almost a colonial condition—harshly imposed beyond explicit political classification, even if such identification remains unstated. Nevertheless, this does not amount to a fully articulated political judgment through which the novel could be analyzed exclusively within a narrowly political framework.

The conflict between the Jungo and the Agricultural Bank offers a revealing glimpse of a latent class struggle, demonstrating how authoritative economic power assesses the value of the Jungo primarily as laboring bodies—human beings whose worth persists only so long as they remain productive.

To read Baraka Sakin’s fiction as pro-war or anti-war propaganda is therefore to misunderstand the very function of narrative realism itself, which does not legislate political programs but exposes the fractures, contradictions, and violences that political discourse seeks to conceal. In this sense, the demand that the novel declare a clear political allegiance is not a critical demand, but a symptom of a wartime culture that seeks to discipline literature into obedience.

An overall assessment of the recent debates surrounding the Jungo and The Messiah of Darfur, and the ways in which these debates are shaped by the ongoing conflict, should open onto new questions and a more visionary mode of dialogue. Such a discourse must move beyond Sudan’s recurring and unresolved impasses concerning identity, social structure, and political complexity. Placing the novel at the center of these divergent interpretations offers a healthier and more productive means of navigating Sudan’s current intellectual crossroads, allowing literature to function as a space of critical mediation rather than ideological confrontation.

Baraka Sakin’s The Jungo: Stakes of the Earth, often regarded as his magnum opus, remains a vast narrative and anthropological exploration that boldly emerges from the depths of Sudan’s social underclass. It gives literary form to lives forged within a brutal social cauldron where human values are systematically eroded and rendered invisible. In doing so, the novel transcends immediate political alignments and affirms the enduring capacity of narrative to document, interrogate, and humanize conditions of structural oppression.

Nassir al-Sayeid al-Nour

February 2026

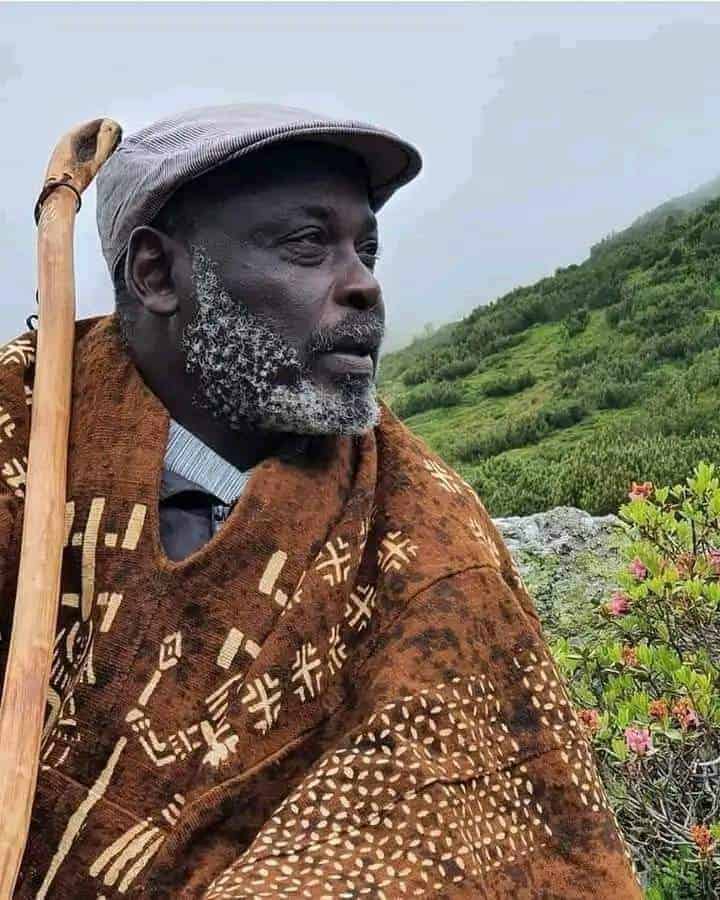

About Baraka Sakin, author of The Jungo: Stakes of the Earth:

Baraka Sakin was born 1963 in Kassala city in Sudan. Considered to be a prominent Sudanese novelist, short-story writer, journalist and activist with international fame and recognition, he is well known for his creative works which have been translated into many international languages. Over the past years, he has been awarded a number of prestigious literary prizes including: Tayeb Salih Prize at the Khartoum Book Fair for his novel The Jungo – Stakes of the Earth, and recently the Ministry of Culture at France awarded him Grade de chevalier dans l’ordre des Arts et Lettres 2023. In 2016, his novel The Messiah of Darfur was published in a French translation, followed by Les Jango in 2020. In France, he also published children’s books as a multilingual edition in Arabic, English and French.

Baraka’s works have been a source of controversial debates about power and social problems. Many of his books were confiscated by the Sudan government where he openly monitored and spoke about political and social taboos. He lives in exile in Austria where he has been nominated in Graz city for their artist-in-residence award.

As an influential figure, Baraka has engaged in many cultural, international events across the globe. He’s written several novels and short story collections which have provided him with acclamation and acknowledgement in the world at large.

Nassir al-Sayeid al-Nour is a Sudanese critic, translator, and author.