The phrase “When God created Sudan, He laughed” is widely circulated within Sudanese society or by foreigners who are related to Sudan in one way or another. Whether attributed to a specific writer or functioning as a form of popular irony, the expression powerfully encapsulates the country’s deeply paradoxical and tragic condition. It serves as a collective mode of social critique—blending dark humor with despair—to illustrate the persistent contradictions, misfortunes, and structural failures that have shaped Sudan’s history, public social culture and political experience.

A Fragile Country & a Forged Identity

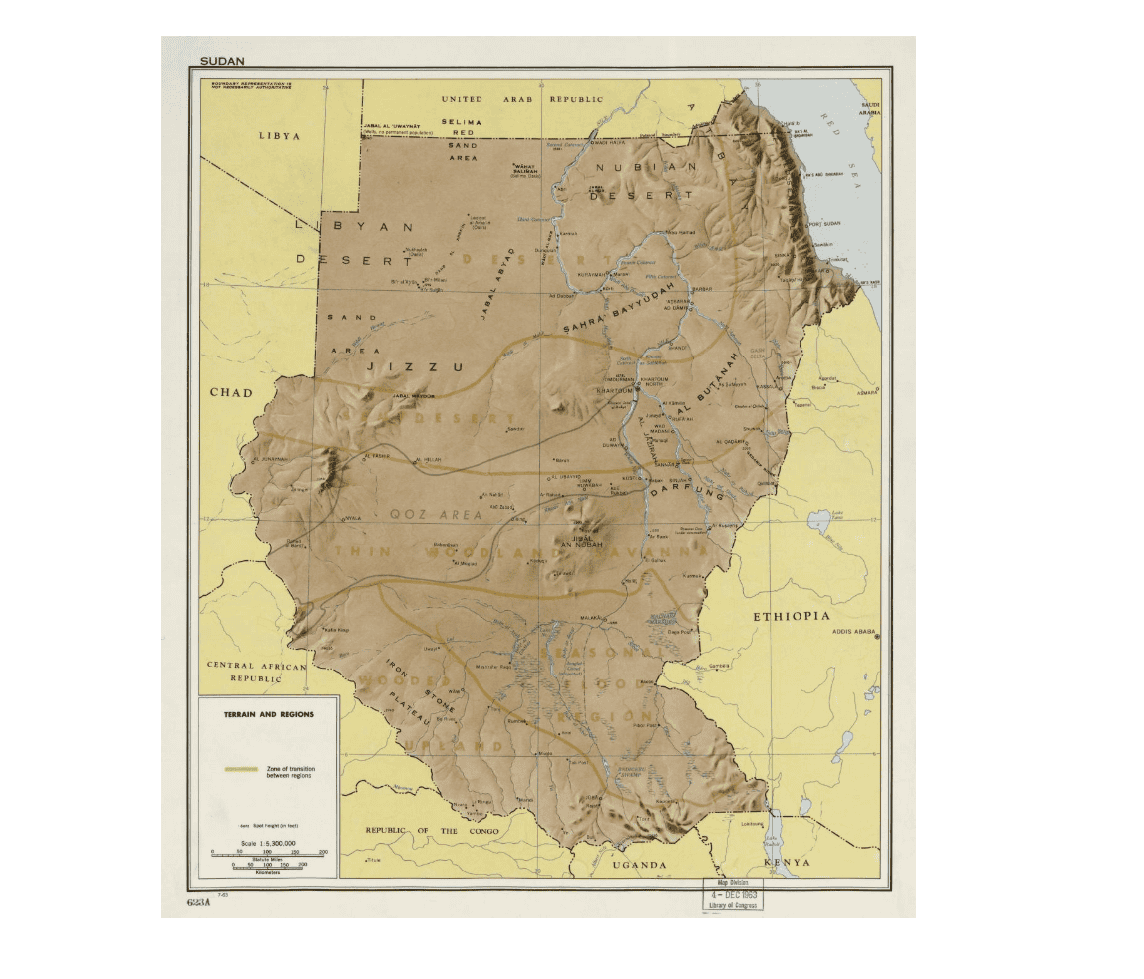

Sudan has indeed been engulfed in war and adversely ravaged by it since its independence from Anglo–Egyptian rule in 1956, a political imperial formula known as condominium, a rare kind of occupation by two states on one country. The result is that the country of Sudan has been torn by recurring internal and tribal conflicts. As a sub-Saharan state, Sudan occupies a unique geographical and cultural position, fluctuating between Arab and African identities, a complexity deeply embedded in its multiethnic and multitribal social fabric. Given its vast natural resources and other natural wealth and potential resources, Sudan could have emerged as a leading Arab–African country on the African continent. In the words of former Minister of Foreign Affairs and prolific writer Dr. Mansour Khalid, Sudan’s political leadership suffered from profound political myopia, a short-sightedness that prevented the state from recognizing the depth and consequences of its structural crises.

Unfortunately, both the state and its people have endured prolonged suffering, trapped in cycles of uninterrupted violence and human devastation. Sudan’s condition exemplifies the fragile state model frequently associated with many Third World countries, particularly within African and Arab contexts, where governance crises persist. These structural failures are evident in the lack of basic human needs, the absence of democratic institutions, widespread corruption, and profound political decay.

Such a state can only be meaningfully analyzed within the framework of the failed state concept, using developmental and political criteria. While a failed state is often defined by dysfunctional institutions and systematic chaos, the Sudanese case reveals a crisis far deeper than an abstract theoretical classification. The roots of this failure lie in the very formation of the state itself, which bears significant responsibility for transforming diversity from a potential source of unity and social strength into a persistent structural problem. What could have served as a foundation for national cohesion instead became fragmented into disintegrated elements that continue to generate instability and conflict.

Sudan’s identity is interpreted from different perspectives, simply because identity has been playing a crucial role in some Sudanese proposals of identity, especially the dominant groups in the Middle and North Sudan who claim to be Arabs and Muslims. Other marginalized groups think differently. They see themselves non-Arab, non-Muslim, and culturally opposed the state that represents the dominant-groups’ view. The dichotomy of Arabism and Africanism has been raised from different platforms, from fighting fields to academia to the general public discourse.

In literary discourse, identity as an elite-driven narrative was articulated by the Sudanese poet and academic Muhammad Abd al-Hai in his work Conflict and Identity.

He argued that a new national consciousness could emerge through a search for the shared roots of Sudanese culture and heritage, grounded in collective symbols capable of transcending ethnic pluralism. From this perspective, Sudan’s rich cultural and historical diversity was envisioned not as a source of division but as a foundation for nation-building based on inclusive national principles rather than tribal or ethnic affiliations.However, this intellectual project remained largely confined to academic and literary circles, as such voices were marginalized and ultimately ignored by entrenched military and political elites who monopolized power and shaped the state according to exclusionary logics.

The Sudanese novelist Mansour El-Souwaim conducted a significant study during the war entitled Narrative as Social Action in Sudan’s 2023 War: Anatomy of Novelistic Discourse and Manifestations of Collective Consciousness. In this research, he critically examined a wide range of creative works, both short stories and novels, in order to analyze how the ongoing conflict has been represented from a narrative perspective. Through a close reading of literary texts produced during the 2023 war, he argued that the persistence of violence in Sudan is sustained by a wounded cultural memory embedded in these narratives. At the same time, he maintained that such literary representations possess a transformative potential: by reworking collective memory, they can contribute to the construction of a new Sudanese identity beyond exclusionary and imagined frameworks. Mansour emphasizes that literary production creates a space of recognition through which women, marginalized groups, and vulnerable communities can articulate their experiences and participate in the construction of a shared national narrative.

The problem of Sudan’s identity dilemma possesses multiple and interlocking layers, a reality powerfully articulated by the South Sudanese diplomat and sociologist Dr. Francis M. Deng, whose intellectual contributions are widely regarded as among the most important writings on Sudanese identity and the cultural and political roots of the national crisis. Through his compelling body of work, Deng demonstrates how the unresolved question of identity profoundly impaired Sudan’s unity and prospects for national progression. He addressed with unusual frankness the hidden and often unspoken factors that rendered coexistence between the Arab-Muslim North and the Christian-African and indigenous belief systems of the South increasingly untenable. In his analysis, the failure to construct an inclusive national identity transformed cultural difference into an irreconcilable political division, thereby making unity not merely difficult but structurally impossible.

In Francis Deng’s formulation, particularly in War of Visions, identity is understood as a relational process: a function of how people define themselves and how they are defined by others in terms of race, ethnicity, culture, language, and religion. In his doctoral dissertation on the question of identity in Sudan, he further specifies this point with striking clarity: “But although the North is popularly defined as racially Arab, the people are a hybrid of Arab and African elements, with the African physical characteristics predominating in most tribal groups.” Through this insight, Deng reveals that Sudanese identity is not a fixed or homogeneous essence, but the product of a historically distorted imaginary: one that oscillates uneasily between claims of Arabness and the undeniable African substratum. In this sense, Sudan’s identity crisis emerges not from diversity itself, but from the persistent misrecognition and politicization of that hybridity.

Killing, Not Debating

The response of the central state in Khartoum to dissenting voices and rebellious regions was not dialogue or political negotiation and recognition, but systematic repression exercised through excessive use of force. This approach resulted in grave human rights violations, including mass killings, genocide, ethnic cleansing, and other widespread atrocities. Such violence disproportionately targeted non-Arab communities in the South, Darfur, and the Blue Nile—regions long classified as marginalized within Sudan’s political geography and political discourse. This marginalization was reinforced by entrenched social stereotypes that ranked ethnic identities along a hierarchical scale, assigning inferior status to certain groups and legitimizing their exclusion and persecution using the state apparatus.

It is fundamentally inconsistent to imagine that the Sudanese identity question could ever be resolved through political or, even worse, military means. In reality, the very formation of the modern Sudanese state has, in many ways, shared responsibility for producing a condition in which violence appeared as the only available exit—a path repeatedly pursued by successive governments. The failure to recognize the “different other,” particularly those outside dominant groups, was not merely a social challenge but a structural problem embedded within the state itself. Official political thinking operated within this exclusionary vision, giving rise to a form of tribal governance in which citizens were not treated as equals—not only before the law, in the conventional authoritarian and hierarchical sense, but through what may be described as a system of silent apartheid.

Historically, Sudanese political parties and movements themselves emerged from sectarian and tribal formations that had long been politicized. As a result, tribal modes of thinking gradually infiltrated modern political institutions, transforming the very concept of power into one structured by racial, tribal, and exclusionary favoritism. Indeed, the manipulation of tribal identities is not unique to Sudan but has deeply marked many pre-state and postcolonial societies in Africa and the Middle East. As the American professor of Yale School of Law and writer Amy Chua observes in Political Tribes, “In many parts of the world including the regions of greatest national security interest… are not national, but ethnical, religious, sectarian, or clan based.”

In Sudan, political polarization and affiliation have long been structured along tribal lines, through which identity itself has been formulated and hierarchized. Certain tribes—particularly those claiming Arab or pro-Arab lineage in northern and central Sudan, especially along the Nile Valley—historically monopolized political power and economic resources, while simultaneously producing a dominant racialized public discourse that legitimized their privileged position. This profoundly unequal distribution of power generated, on the opposite side, deep and enduring historical grievances among marginalized tribes and peripheral regions that experienced systematic exclusion on a tribal basis.

In the modern nation-state, however, tribal affiliation cannot serve as a consensual foundation for nationalism or collective identity, especially in the absence of an inclusive civic consciousness. Yet in Sudan, the traditional unit of the tribe was politically consolidated and instrumentalized by successive regimes without regard for its destructive long-term consequences. As a result, power ceased to be organized around the principle of equal citizenship and was instead redistributed through sectarian and tribal patronage networks, transforming large segments of society into political subjects defined by semi-racial and tribal discrimination.

From an anthropological perspective, the tribe can be understood within the framework of the historical evolution of human societies as a social form of organization. It cannot, however, provide a legitimate basis for modern political authority—although, in practice, it has repeatedly been manipulated as such. In Sudan, this manipulation hollowed out the very meaning of citizenship and entrenched a system in which belonging was determined not by rights, but by lineage.

The Road to the War

In effect, state policies implicitly treated certain populations as if they were undeserving of life itself. These policies reshaped Sudan’s geographical and social landscape in irreversible ways. In 2011, Southern Sudan seceded to become the independent state of South Sudan, following one of Africa’s longest internal conflicts, during which nearly two million people were killed. All previous attempts at integration had failed to render national unity a viable or desirable option. Yet a crucial lesson remained unlearned by political elites: the legitimate rights and lawful claims of marginalized communities were consistently ignored, even as an alternative and irreversible destiny was already taking shape.

Likewise, all other marginalized regions in west and east were a field to implemented the mentioned polices and the result the same. Additionally, the culminating moment of the imbalance of intentional developmental policies was erupted in the ongoing brutal war in 2023 between the Sudan Army represented the legitimate central government and the Rapid Support Forces a para-militia established mainly to oppressed the insurgence armed movements in Darfur and Sudan’s elsewhere restive regions.

The overlapping social, historical, and political competitions over power created the conditions for Sudan’s prolonged descent into a devastating war. Although war is not a new narrative in Sudan’s political memory, the current conflict represents a qualitatively different rupture—one that is unprecedented in both its nature and its consequences. Its logic, scale, and patterns of violence remain deeply disturbing and, in many respects, difficult to comprehend.

This rupture must be understood against the background of the turbulent period following the December Revolution 2019, which led to the demise of Islamic regime but was soon followed by the reassertion of military dominance over the transitional civilian government. The collapse of the fragile civil–military partnership transformed political rivalry into open armed confrontation, thereby converting a contested transition into a full-scale war that has fundamentally altered the trajectory of the Sudanese state.

Islamization of Power

The crisis of Sudan’s identity question reached its peak when the Islamic Movement seized power through a military coup in 1989, abruptly interrupting the democratic evaluation and launching unprecedented political mobilization on ideological grounds. This marked the emergence of a new and deeper dimension of crisis, one that further devastated an already fragile nation struggling to rise under the weight of its contradictions. Over three decades, Sudanese society was subjected to a doctrinal project that imposed an unprecedented political orientation and a new legal order claimed to be grounded in Islamic rule. In this process, core Islamic rituals and practices were transformed into a rigid political ideology that ultimately served the interests of a narrow elite gripping power in absolute terms.

Despite its religious claims, the Sudanese Islamic Movement, as a political project seeking domination, exercised power in ways that led the country into a perilous condition that gravely threatened national unity. This dynamic corresponds closely to what the political thinker Hannah Arendt observed: “When a movement, international in organization, all-comprehensive in its ideological scope, and global in its political aspiration, seize power in one country, it obviously put itself in a paradoxical situation”.

The regime systematically restricted religious freedoms and stubbornly denied the deep diversity of Sudanese society in its religious, linguistic, and cultural expressions—diversity that the Islamic Movement deemed incompatible with its conception of “pure” Islamic rule. Consequently, the definition of Sudanese identity as a multiethnic and multicultural nation became increasingly vague and hollow, replaced by an expansive and abstract Islamic identity in which national borders and local histories lost their significance. In the Sudanese social context, this effectively meant imposing an Arab-Muslim normative model upon populations who neither belonged to it historically nor culturally, thereby deepening exclusion and intensifying the crisis of national belonging.

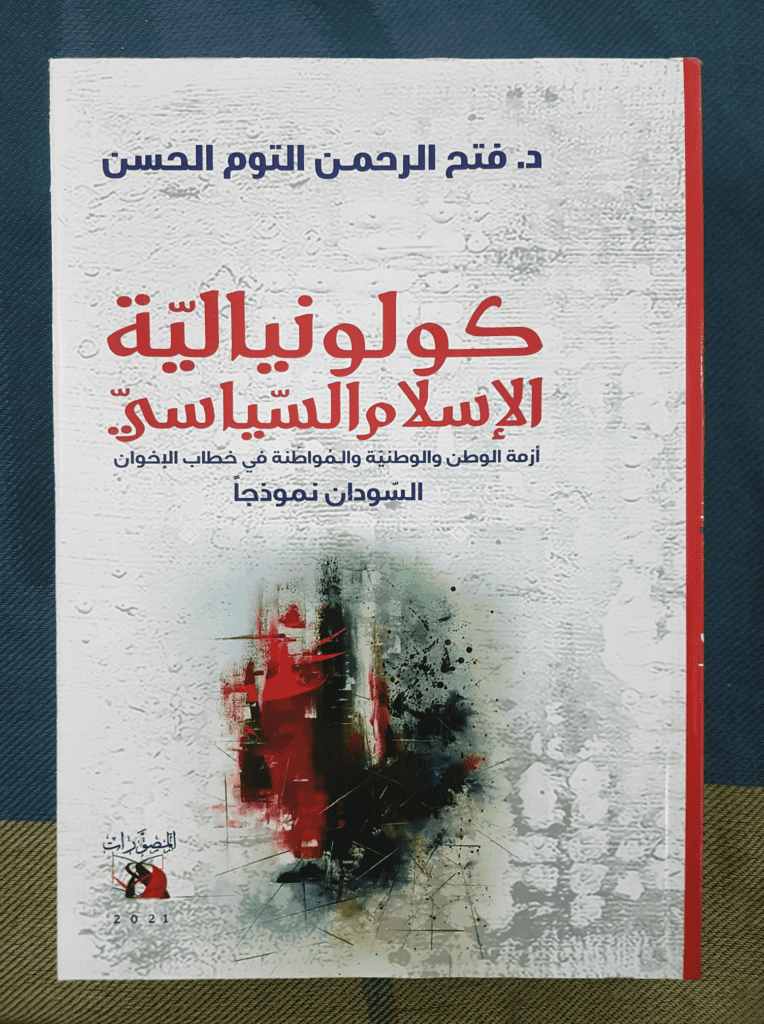

Sudan experienced a form of political theology accompanied by systematic repression that ultimately contributed to the partition of the country into two separate states and to the perpetration of grave human rights violations against its population. The Sudanese professor of philosophy Dr. Fatahalrahman El-Toom Hassen offered a penetrating critique of this controversial ideology in his important work Colonialism of Political Islam, in which he provides a profound analysis of the crises of nationalism, citizenship, and state formation within the framework of the Muslim Brotherhood movement, using Sudan as both a field of investigation and an analytical model.

by Dr. Fatahalrahman El-Toom Hassen

In this study, he excavates the intellectual and moral foundations of the theocratic state that the Islamic Movement sought to establish in Sudan. He argues that this project was fundamentally unqualified to claim moral or religious legitimacy, as the widening gap between ideological slogans and political reality exposed the concealed interests and material advantages that were secured under the cover of religious pretexts. In this sense, political Islam functioned less as a moral order than as a strategy of domination, instrumentalizing religion to consolidate power and exclude opponents.

In common practice, Islam in the Sudanese context has historically taken the form of a synthesis between folk religious traditions and Sufism, deeply rooted in and underpinning popular religiosity. This Sudanese version of Islam was generally characterized by tolerance and moderation, and it readily absorbed popular cultural and artistic expressions without coming into conflict with official or orthodox forms of religious authority. Through this accommodative tradition, religion functioned less as a rigid legal system than as a lived social culture, integrated into everyday life and collective identity.

The British scholar Spencer Trimingham highlighted in his classic study Islam in the Sudan the decisive historical influence of Sufi shaykhs on Sudanese society. He observed that “they found a fertile soil among the sedentaries in Sudan and easily won the hearts of the intellectually backward masses with their devotional fervor and miracle-mongering”. Trimingham further emphasized that their authority extended beyond the spiritual sphere into the political domain, where Sufi leaders often mediated power, loyalty, and social order. Through this tradition, a culture of religious tolerance and social accommodation guided Sudanese society for centuries—until it was rapidly destabilized by the advent of modern political Islam, which replaced this pluralistic religious ethos with an ideological and coercive project of domination.

Where to go from here?

Remarkably, Sudan stands as an exceptional case in the region in its repeated popular demands for democracy and its persistent overthrow of military dictatorships in the post-independence period. Three major civil uprisings—in 1964, 1985, and 2019—successfully dismantled authoritarian regimes; yet each democratic opening was soon followed by the return of military rule. Despite this cyclical pattern, popular resistance has never ceased. The intertwined complexities of violence and identity have continuously driven Sudan’s uncertain future toward an unpredictable destiny. The ongoing war has reshaped the country on multiple levels—fracturing the social fabric, redrawing geographical realities, and entrenching new political polarizations—to such an extent that Sudan will never return to its previous form.

The consequences of war have also generated a new Sudanese narrative of exile. As a result of mass displacement and forced migration, more than twelve million Sudanese have fled the country, producing a vast diaspora in which new forms of nostalgia, loss, and longing are being articulated. This emerging exilic consciousness has become an integral part of contemporary Sudanese identity.

When a country is submerged in a bloody conflict and its international image is disfigured by genocide, mass rape, and systematic brutality, there can be no moral exoneration for its political and cultural elites. Responsibility is not solely political. It is also profoundly cultural and intellectual. Segments of the educated elite have, through discourse and justification, contributed to sustaining the logic of war, regardless of the claims under which it was waged. Instead of forging a unified ethical discourse that rejects violence on human grounds, war entrepreneurs succeeded in reshaping intellectual spaces to serve their political interests, thereby normalizing destruction and silencing alternative visions of peace.

Conspiracy theory is widely invoked as a framework for explaining the hidden causes behind Sudan’s tragedy. In political terms, this often refers to the role of foreign states that support rival domestic actors in order to pursue their own strategic interests in the region, reducing Sudan to little more than a testing ground for competing agendas. Yet the reality is more complex. External intervention has not created the conflict from nothing; rather, it has operated upon deep internal fractures already embedded in Sudan’s political and social structures—fractures that were historically shaped by patterns of exclusion, inequality, and divisive state formation. In this sense, foreign involvement has amplified and exploited internal differences whose very foundations were laid upon an enduring logic of division.

The war cannot be justified by cultural or social claims, nor can it be elevated as a struggle to attain a non-existent identity sustained only by irrational and fabricated historical conceptions. Rather than expressing an authentic quest for belonging, the conflict reflects a profound failure to confront the realities of Sudan’s plural society. Across generations, Sudan has passed through repeated experiences of failed state-building, unable to transform the collapse of one dream into the revival of another that might sustain a viable national life. Instead of moving from the death of illusion toward a renewed project of citizenship, the country has remained trapped in a cycle where each shattered vision gives birth only to a new form of crisis.

Nassir Al-Sayeid Al-Nour

February 2026

Nassir al-Sayeid al-Nour is a Sudanese critic, translator and author.

Featured image: Sudan : terrain and regions. United States. Central Intelligence Agency. Created / Published [Washington, D. C.] : [Central Intelligence Agency], [1963]