“President Bush announced that we were landing on Mars today … which means he’s given up on Earth.” – Jon Stewart, The Daily Show

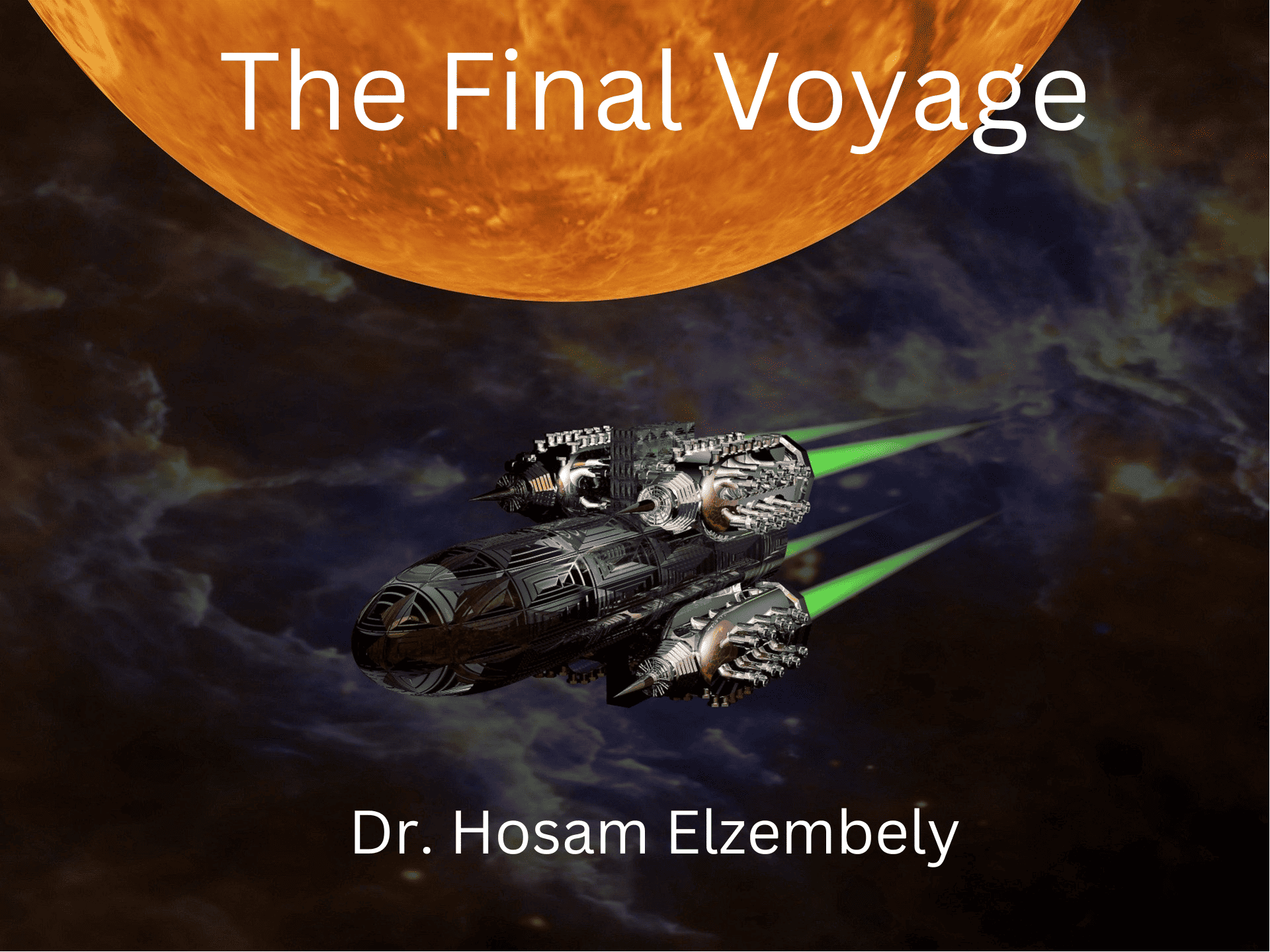

This is a study of The Final Voyage (2023), a soon-to-be-published YA novel by Dr. Hosam Elzembely, the director and founder of the Egyptian Society for Science Fiction (ESSF). It won the Sci-Fi award in the National Academy of Science and Technology 2022 in Egypt. The story is set on Mars after a natural disaster has befallen Earth, with the crust of the planet fracturing and spewing out lava, forcing the whole of humanity to leave in a frantic craze. The last of these trips to the unknown is the focus of the story as seven individuals recount their own tales of daring do and how their lives brought them to where they are now. And it’s not just humans who have stories to tell, or things to do.

Needless to say, comparisons have to be made to fully comprehend and appreciate the contribution this story can and is making to the corpus of sci-fi literature on such a hackneyed topic as Mars. The red planet has been a running obsession of scientists (from astronomers to botanists), romantic futurists and authors – West and East alike – from 1877 with the supposed discovery of canals on Mars. Out of this cauldron of hopes and dreams, and nightmares, came classics like War of the Worlds, Invaders from Mars, Stranger in a Strange Land, A Princess of Mars, The Martian Chronicles and most recently the novel and movie The Martian and also The Space between Us. Not to forget Aleksey Tolstoy’s Aelita and a less well known Soviet movie Battle Beyond the Sun (1959). We Muslims have a running love affair with Mars too, certainly as Arabs and Egyptians. Cairo, Al-Qahira or The Vanquisher, is the old Arabic name for Mars.

So, how does a ‘Muslim’ Martian story differ from a European appraisal, as the bulk of those who have written about the red planet have come from a Christian culture? Russia is part of the Christian world, even in its communist phase, and the only other two non-European exceptions I can think of are Huihu’s Chinese SF novel Remembrance of Mars and Israeli author Lavie Tidhar’s Martian Sands. (There’s also Mehdi Bonvari’s Rivers of Mars, if it ever sees the light of day, in English or Farsi). From the briefest glance at Dr. Hosam’s novella, I can sum up the answer in a single phrase – the playground of the soul. That’s what the Final Voyage is all about, from start to finish. It’s about religion and spiritualism and finding yourself. But this is more a race awareness than individual revelation. One of the first ever Arabic SF stories set on Mars, Ahmed Raef’s play The Fifth Dimension, has human explorers finding an intelligent species on Mars that worships God and have their own sharia and rule based on consensus, an Islamic maxim. The fifth dimension, incidentally, is the dimension of the spirit. And the human travelers went to Mars specifically to get away from the Cold War threat of nuclear annihilation.[1]

There are other things in Final Voyage of course, such as prospecting for water and coming into contact with a non-organic alien species and fighting off future threats, AI robots working on their own volition, and the storytelling format. It’s a science-heavy book, and a small explosion of a book – the first of a trilogy, leaving you with many an unanswered question – but it all tracks back to the same thing: The soul and how it relates to everything beyond it, whether it be other people or the environment or God or even itself and its moral and emotional evolution. You can see this in the penultimate scene where two of the protagonists – a young couple – proudly proclaim that they’ve changed Mars forever. It’s not the red planet on account of the god of war anymore but the planet of romance, the colour of the heart.

We’re quite a romantic bunch, you’ll be surprised to know. But we understand romance differently than in the West, for instance, the English expression out of sight out of mind. The Arabic equivalent is what is far from the eye is far from the heart. In English, you admonish someone for acting before thinking, while we in Arabic say what’s on my heart is straightaway on my tongue. The heart is understood in intelligible terms, as a thinking as well as feeling entity that energizes the mind and guides you down the right path. The great Sufi scholar Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali (1058-1111 AD) famously posed what it is that makes the heart happy. He said the nature of something determines what makes it happy. For the eye, it is seeing beautiful things. For the ear, lovely melodious sounds. For the heart, it is knowledge of God. The analogy he then used was chess – once you learn the basic rules you become obsessed and won’t rest till you become the best at the game. He then adds that if you met a government minister, a man of high stature responsible for so many important things, you would feel honoured at the opportunity. Imagine then what would happen if you met God, the person of the highest status by far and responsible for everything, such as the air that you breathe. Imagine how happy you would be? Ghazali finishes off by saying that what makes the soul happy is what makes the body happy, animalistic pleasures, but these pleasures die with the death of the body. The heart however embraces death because it means being freed from the shackles of the body and leaving the world of darkness and entering the world of everlasting light.[2]

You’ll also notice that words like heart and soul and the mind or psyche are being used interchangeably, an affliction of the Arabic language. Again, they all track back to the same thing. Playground of the soul, playground of the heart, the spirit, etc. Dr. Hosam’s novel, while in the 22,000 words range, is a mental riot.

The key to understanding the book is really the flashback sequences that we are introduced to through the vehicle of storytelling. There is more to this than meets the untrained eye. Growing up, Dr. Hosam was a big, big fan of The 1001 Nights and he even wrote a draft novel as a kid modeled on it. Even in his science fiction he frequently incorporates fantasy elements, such as solving riddles to go to the next stage of the story – a common literary technique in folklore and Arabic storytelling.[3] As scientific as he is – an eye surgeon and university professor, and human development expert – his instincts are still grounded in oral storytelling from Arabic and Islamic history. Flashbacks and flashbacks within flashbacks are common fare in the Western novel, true enough, but they don’t tend take on the form of folklore and fantasy epics. That’s a very distinctively Oriental trait, and in mainstream SF this is downgraded even further. In The Postman you have a charlatan who tells entertaining tales to eke out a living, and then he creates the greatest lie of all – that there’s a new central government and Union and that he’s a representative. Campfire stories are told in a post-apocalyptic setting, as if it’s a badge of dishonor. Just take a look at Battlefield Earth, where campfire stories are literally meant to keep man primitive, and not challenge the will of the gods/alien invaders. Similar corollaries are to be found in the Philip K. Dick stories “The Great C” and “A Surface Raid”, or the old Planet of the Apes TV series. For us, the great storytelling epics – Shahnameh, 1001 Nights – were written down specifically at the peak of our civilizational prowess. Consequently, we make fond associations and go back to them, every now and then, for inspiration and moral instruction.[4]

The first story recounted in the novel, interestingly, is by a Christian named Michael, and you get a distinctly uncharming portrayal of him as a cynic and skeptic. It’s only by the end of the novel that he regains his faith and finds true love with a fellow Christian woman. In the meantime, he has adventures on the red planet, with a Muslim crewmember and they bond as comrades in these prickly, life-threatening situations.

For the benefit of the Western audience, this is a common technique used in Egyptian literature and cinema, the national unity motif, just like in American cinema where you have a white and a black cop or soldiers in a foxhole together who again are a white and black duo, or a Jewish person and an Italian American. Another one of the recounted tales, by a Muslim woman, begins with a flashback of the hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca. But then she lets the cat out of the bag. At one point in time, she was a member of a – shock, horror, disbelief – UFO cult!

Turns out that humanity was in a sorry state on Earth, even before the earthquakes and volcanoes consumed the land. A microbial pandemic had spread like wildfire on the planet – some suspect it was bioweapon or a harvested virus that escaped the laboratory – and it attacks the brain to the point of turning humans into Stone Age cavemen. In this horrendous context, a UFO cult rises to power that promises salvation, through flying saucers, but also claims that it can unite mankind under a single banner.[5] That’s why their preachers wear beards like Muslims and use the Cross and Stars of David at the same time. And they exploit the primitive cavemen to boot.

Being on Mars is a kind of homecoming for her, a chance to redeem herself. You also get the distinct impression in this chapter that human beings have outstayed their welcome on Earth and that mother nature was getting its revenge against mankind through the plague. Once this epidemic was sorted out, but humanity still didn’t reform itself with its insanity and pollution, you find the Earth’s crust rebelling. And so the voyage to Mars, by extension, is a chance for the crew and humanity to redeem and remake itself.

In the here-and-now storyline, a baby girl named Sarkha (Scream in Arabic) is kidnapped, the first child born on Mars, and the crew in various adventures trying to find her and figure out who could have done such a thing on an empty planet. In the process, they come across alien life forms that are crystalline and yet perfectly sentient and capable of marshaling their forces against human intruders. That’s when a higher intelligence comes to play, a mysterious entity simply known as the Mother Intelligence. She warns them that while humanity is a dying breed it still has so much destructive potential in it. In their not-too-distant past humans made a startling genetic discovery that could produce a whole new breed of hostile life forms and the Mother Intelligence desperately needs their help to prevent this from happening.

There are clear allusions here to environmentalism and notions of mother earth or nature, something that shows up frequently in SF penned by Arabs and Muslims. Iraj Fazel Baksheshi’s novella A Message Older than Time has an older sentient species leaving a message to the future inheritors of the Earth, mammalians and ape-men, of the meteorite that killed off the dinosaurs and put an end to their dominion. But in a flashback you find the scientist who made the recording saying that the selfishness and petty disagreements between the different city-states of their species prevented them from destroying the meteorite early on with a coordinated missile attack. And even without the meteorite they were a doomed species, deforesting the planet and using up its life-giving resources. They’d lost their birth right to their mother, Earth, lest the human inheritors do the same thing the next time a meteorite comes our way. I have a story, “Cat’s Paw”, that I won a prize for from the ESSF where an inventor uses trees as lampposts – natural solar power. His inspiration for this, and my inspiration for the story, was seeing a cat scratching its claws on a metal lamppost thinking it was a tree. When I put pen to paper I then recollected a friend of the family telling us how nature is always better – a common Muslim sentiment – giving the example of a tree. It protects from the sun better than a roof does, because it has several layers of branches and leaves, and lets in the wind so you don’t get choked. We can add, and I did in the story, that its’ a habitat for birds and insects and adds beauty to the world through chirping, not to mention a source of food for cats.

But to fully understand this episode in Last Voyage you have to look at one of the earlier flashback sequences. In chapter 4 “The Robot Maker”, my personal favourite, you have a female crewmember talking about her father the robot inventor. He’s also a genius mathematician who believes he’s found the secret to creation – located as it is in the human soul and expressed in what he calls ‘Floating Mathematics’. Why would he look for it there? Because of Quranic verses and religious sayings talking about how God breathed his spirit into the clay body and made it sentient. He adds however that his maths isn’t enough because you can only unlock these secrets if you engage in riyadat al-nafs (exercises of the soul) and jihad al-nafs (doing jihad or war with the self), all explicit Sufi terminology. Knowing the secrets of the universe means having access to incredible power, and you can easily misuse that power or be corrupted by it and blow yourself up if you can’t discipline your desires and primordial instincts first. (Recollected Al-Ghazali from above).

To put his maths to the test, he programs his robots to override Asimov’s three laws. He is aware of the risk he’s taking since gifting them with self-awareness and individual pride and jealousy could make them destructive and rebel against their creators. Even so, he decides the risk is worth taking. It’s at this penultimate scene that someone asks the crewmember recounting the story if the robots went on a murderous rampage. She laughs it off instead. They did mess up the apartment, each blaming the other for the mess, but no more. With time they evolve morally and one asks his inventor if he has a soul and if he should worship him. The man says absolutely not. God is the creator, not me. And the robot says he will pray to a creator of his creator, and hope that God will grant him a soul in answer to his prayers.

Two of the robots do in fact rebel, but in a benign way and head off to Mars, before the human crew, and do a better job prospecting for water than the humans. Interestingly one is called Abqarino, from Arabic abqari which means genius. The other is Bahlul, the Arabic name for court jester. Arabic SF is quite enamoured with robots and we often have robots who learn to be human.[6] Not always but frequently. In the case of Dr. Hosam, there’s a religious angel. In his first published novel, The Half-Humans, you have a female biological android (she’s battery power, however) who shows tremendous gumption and ingenuity to the point that the hero begins to fall in love with her. In a talk about the novel Dr. Hosam explained that she, essentially, has a soul and that he’d always been inspired by verses in the Quran that say everything worships God – even animals and plants – and that everything, even inanimate objects, have a kind of residual consciousness to them. (Hence, the crystalline aliens). Sufis, needless to say, love these interpretations of the Quran. Venturing out into space to recapture your lost humanity is another theme pursed by Dr. Hosam Elzembely, such as in his dystopian novella America 2030. The USA, once the bastion of liberty, becomes a dictatorship – behind the scenes – and devises a doomsday device to defeat the other blocs of states trying to stop its repeated aggressions. The heroes, a multicultural crew, can’t stop the tide of the war however and what’s left of humanity has to leave the planet in search of a new home, but united together as a single human race. Even Americans join the mother ship before it departs.

So, finally, to tie everything together the Mother Intelligence explains that while a creator of life it does not know who its creator is and suspects there is an ultimate creator in the universe – what human beings call God. The Mother Intelligence adds that the floating equations are in fact the keys to the secrets of the universe and will defend mankind, and the universe, from the aforementioned manmade biological theat. (I presume in the sequels). They can also be used as a universal lingo. Remember that the crystalline entities were just protecting their home turf and meant no disrespect. (Muslim authors often have a United Nations ruling the Earth in the future, or a United Nations of the Galaxy – see Iraj Fazel Bakhsheshi’s short story “The Beginning of Life” and his novella Guardian Angel).

The message of The Final Voyage, apart from national unity, is that we’re all human at the end of the day. We all want the same things. To be in love, and to be happy. And religion allows for that if not insists on it, and gives you the tools for the job. Happiness and love here aren’t understood in a hedonistic or utilitarian fashion. Sex is not confused with love and love here means commitment as well as passion. That’s certainly what Sufism is all about, a la Ghazali. Nobody converts to Islam in this novel, you’ll notice, and in Arabic usage, Sufism means mysticism and is used to describe other mystical cults or traditions in other religions.

That at the end of the day is the distinctive Muslim contribution to sci-fi stories set on Mars. If you want to turn the red planet green, and that’s what the heroes of the story are hoping to do, you have to sow the seeds of love on the planet of war. And that means doing war with your base instincts to redeem yourself and so earn the right to set down roots on the so-called red planet. Mars, in Muslim eyes, is the playground of the soul.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Dr. Hosam Elzembely for providing me with an early copy of his novel, answering my queries and reviewing this paper in draft form.

[1] Please see Jörg Matthias Determann, Islam, Science Fiction and Extraterrestrial Life: The Culture of Astrobiology in the Muslim World (London: I.B. Tauris, 2020), 89-90.

[2] See Muhammad Abd Al-Munim Khafaji, Literature in the Heritage of Sufism (Cairo: Dar Gharib, 1980), pp. 117-118.

[3] Please see an earlier review of mine of Dr. Hosam’s works, “Better Late than Never: The Transmutations of Egyptian SF in the Work of Hosam El-Zembely”, Foundation: The International Review of Science Fiction 131, vol. 47, no. 3, Winter 2018, pp. 6-14.

[4] You see this wherever you go. My friend, SFF author Ahmed Salah Al-Mahdi, became captivated by writing at an early age because of the fairytales and epics he learned as a child from his family. (Please see “Islam and Sci-Fi interview of Ahmed Al Mahdi”, Islam and Science Fiction, 17 June 2017). And much Arab SF writing as a consequence is borderline fantasy, given our heritage. As for 1001 Night, we have Mehdi Bonvari’s in his own Mars novel, since he has a brother and sister team who are separated at a young age only to become reunited, almost on opposite sides of the fence. I recognized this feature straight away from the 1001 Night and queried him on it and he confirmed it. I even made a point about this in my presentation “Cyberpunk Traditions Outside the United States – Panel” with Hirotaka OSAWA and Valentin D. Ivanov, at Chicon 8, 1 September 2022. We regularly blend our myths into hard sci-fi settings and Mars it seems is no exception.

[5] Once again, see Determann, Islam, Science Fiction and Extraterrestrial Life, pp. 37, 101, 103-104, 105-113, 115, 117, 120-126, 128-137, 171-172. I’m a member of the RACS network myself (Religion and Astrobiology in Culture and Society) and you find amazing commonalities between UFO cults in the West and in the East.

[6] Please see Ahmed Salah Al-Mahdi’s [translated] short story “The Naked Robot”. The robot in question, a human-looking android, doesn’t like being stripped of its work clothes when older mechanical models take its place. Later he steals the overalls of human, knocking him out to be sure, but doesn’t harm him. And that after the android workers broke their programing and began to kill each other to steal their power units.

Hope you guys all like this. In the meantime, here’s my sci-fi website: https://emad-sci-fi.my.canva.site/

And my newspaper column, also on SF: https://theliberum.com/category/unconventional/emads-sf/