In A War of Colors: Graffiti and Street Art in Postwar Beirut Nadine Sinno explores the graffiti and street art of the city of Beirut after the Lebanese Civil War. She describes how the revolution and other subjects shaped the art in the city and how the philosophy of graffiti artists works. In this conversation, she tells us more about the work on A War of Colors and what difficulties she came across while working on the book.

When did War of Colors become a book project?

This is a long and complicated story. I had moved to the US in 2001 to pursue higher education. Every year I would go to Lebanon. I remain connected to the region for personal and professional reasons. Every time I would walk around Beirut in the summers, I would notice some new graffiti or street art pieces that did not exist in my prior visits. I was intrigued and moved by what struck me as different unprecedented types of graffiti and street art. This included things like portraits of singers or poets, cartoon characters, or simple stencils. As you might know, I was born and raised in Lebanon during the war, so my memories and perceptions of graffiti used to be limited to logos of militias, sectarian slogans and dehumanizing slogans between different political factions in addition to, of course, the occasional casual doodling. By summer 2014, I became convinced that this innovative type of graffiti was resembling a substantial corpus of work, and it wasn’t just isolated pieces here and there. I was very intrigued on the professional level and on the personal level. I was touched by the efforts of young people who were transforming the city. Initially, I was committed to writing a peer-reviewed article. I didn’t have a book in mind. When I submitted the article, it came back with some very valid critiques that suggested that, you know, maybe I was all over the place because it included way too many different types of graffiti and street art. The blind reviewers indicated that maybe I was trying to cover too much, that I was a little bit too ambitious. So, I revised the article and narrowed it down. I only included murals, and the article came out in 2017. But, there was a part of me that always knew there was a lot more. I had taken way too many pictures that were not discussed in the article. And then I started to present my graffiti-centered research at conferences. I also continued to take pictures every summer. So, eventually, I had thousands of pictures, and I was presenting at conferences and different mentors and kind colleagues said, “You know, Nadine, this deserves to be a book.” And in summer 2020, I would say, is when I seriously committed to turning all this research into a book. There was the pandemic. So, I also had the time and the space to sit down and just consistently work on writing the book.

When you took photos of the street art and graffiti, what was the most striking street art for you while doing fieldwork for the book research?

I think different graffiti and street art pieces struck me as surprising or exciting for different reasons and at different times in my life. So, for example, because I had only seen the huge posters of Arab leaders on the walls of the city my entire life when I started seeing the murals of artists and poets, and specifically the portraits of Fairouz and Sabah and Mahmud Darwish, I was astounded, right? So those pieces were for me very striking. I was really excited that they were being commemorated. But then also I would see the murals of cartoon characters like Bomberman and Grendizer, and those too made me smile and pleasantly surprised me because they reminded me of my childhood and the cartoons we used to watch as kids. Other graffiti, like the tags, were surprising in their own way because I was thinking, you know, how amazing that the artist managed to reach really high or hidden places and to produce such meticulous work. I was also struck by more crude types of scrolls that referenced the Lebanese Civil War and the sectarian system. And I thought, oh my God, these scrolls are really daring. They really showed a strong presence of anti-sectarian activists who wanted to remind people that the Lebanese Civil War had not truly ended. The gender and sexuality graffiti surprised me as well because I thought, you know, these conversations were happening now on the streets. I feel like graffiti pieces are like different songs that resonate with us at different times in our lives, and they remind us of different memories, some traumatic, some pleasant, and so the different pieces struck me as unique for different reasons.

“Grendizer” by Ashekman. Photo by Nadine Sinno and William Taggart.

You mentioned you look at difficult questions concerning aesthetics and style, as well as topics like homosexuality and these kind of issues. When did you know that you wanted to look at these specific topics in your book?

In terms of how these topics emerged, I do look at different, and difficult questions, including ones yes, related to gender and sexuality, as well as ones related to political corruption and environmental devastation. And in many ways, this is something I like to give my husband William Taggart a lot of credit for because he was always persistent in reminding me that I should let the data speak for itself and let the data determine the questions and the topics.

At the first stage, I decided to focus on collecting as much graffiti and street art as I could. And I would take informal notes about the graffiti that I saw. Also, I would record my feelings or my impressions, and I would talk with colleagues and friends and family about them. I remained open, as I just amassed tremendous amount of data, thousands of pictures, really. And then later, I was able to group them under recurring topics and subtopics until I finally narrowed them down to the few general themes and research questions that you see in the book.

And can you tell us a bit about what the street art pieces are trying to tell us? What are the stories behind them, and what are the characteristics maybe?

Sure. I think, again, as I always say, the different pieces tell us different things. So for example, in the case of the graffiti that focused on portraits of singers, journalists, and poets, the graffiti makers were likely telling us these creative individuals deserve to be our role models. These are the people that are not as highlighted in the Lebanese public sphere as much as they should in part because political leaders and their slogans and pictures have always been there on the wall. So it’s time to honor other types of role models. The graffiti that focused on gender and sexuality tell different stories about the desire of people with minoritized identities to also become more included in the Lebanese public sphere. On the other hand, if you think about the graffiti about the environment, these are activists or people who care about the environment saying, we need to stop. We need to stop neglecting the environment, and we need to reclaim green spaces. They should be open for everybody. And then of course, there is the revolution graffiti, which was about the protests and the aftermaths of the Beirut Port blast. These are telling us, you know, the political system has to change and everybody should be part of this project, and we should unite as opposed to being divided as a Lebanese people.

And the artists that you talked with about your book, how did they react to your inquiry and how did you approach them about your work? Like, was it difficult to get access to them, or were they willing to talk with you about their own work? So how was it, maybe you can give a bit of insight about this aspect of your work.

For the most part, the artists that I was able to identify and contact welcomed me warmly. They were excited because they were very passionate about their work. And I believe they appreciated that I was putting in the work to track down the graffiti, to photograph it, and reach out to them. I was taking it seriously. I believe that the artists that had included their signatures and were part of the graffiti scene felt comfortable talking to me about their work. And they’ve talked to journalists about the graffiti pieces, about their philosophies, about their take on street art and graffiti, and about their motivations. And so, giving them an additional space to share their stories and struggles made, I think, for a richer narrative, and it was mutually beneficial: For me, it personalized the project as well. I’m a cultural studies person, so the work for me is the center. It felt important to reach out to the graffiti makers that I was able to reach out to. And their courage, their analysis, everything propelled me to persist, and some of them also suggested I talk to others. So that was useful. I would have loved to talk to every single graffiti-maker, if you ask me, but that wasn’t feasible. Also, you know, the pandemic and other personal issues disrupted my fieldwork. So that was hard. I regret not being able to talk to more people, particularly, the graffiti makers behind the revolution graffiti. But I was lucky. I was able to find a lot of information through Lebanese newspapers and websites.

How do the graffiti and street art vary among artists? Like they are reacting to the political events in Lebanon, of course, but are they similar in terms of the artistic themes that they’re using? Or are they different from each other?

I think they’re both similar and different. I think they converge and diverge in different ways, right? So, the portraits are similar in the sense that sometimes the graffiti makers are commemorating the same artists. There are, you know, numerous Fairouz portraits. Sabah is also someone who shows up more than once. Also, all the portraits obviously focus more on depicting faces. The portraits of famous cultural icons were also common during what I consider a more stable time in Lebanon. So, in general, there was some political stability early in 2014 and 2015. But then if you look at the graffiti that was dedicated to the protests, you see that that kind of graffiti is focused more on the struggles of people, on the desire for freedom, on maintaining hope, and on transcending political divides. The artists have different personal styles, I think, but at, at the very least, some of them are similar in the sense that they address topics that run across different individual artists.

“Sabah” Mural by Yazan Halwani. Photo by Nadine Sinno and William Taggart

And, you are looking at the Lebanese Civil War as well. How is it still present in the art, and why is it still a topic for the graffiti artists?

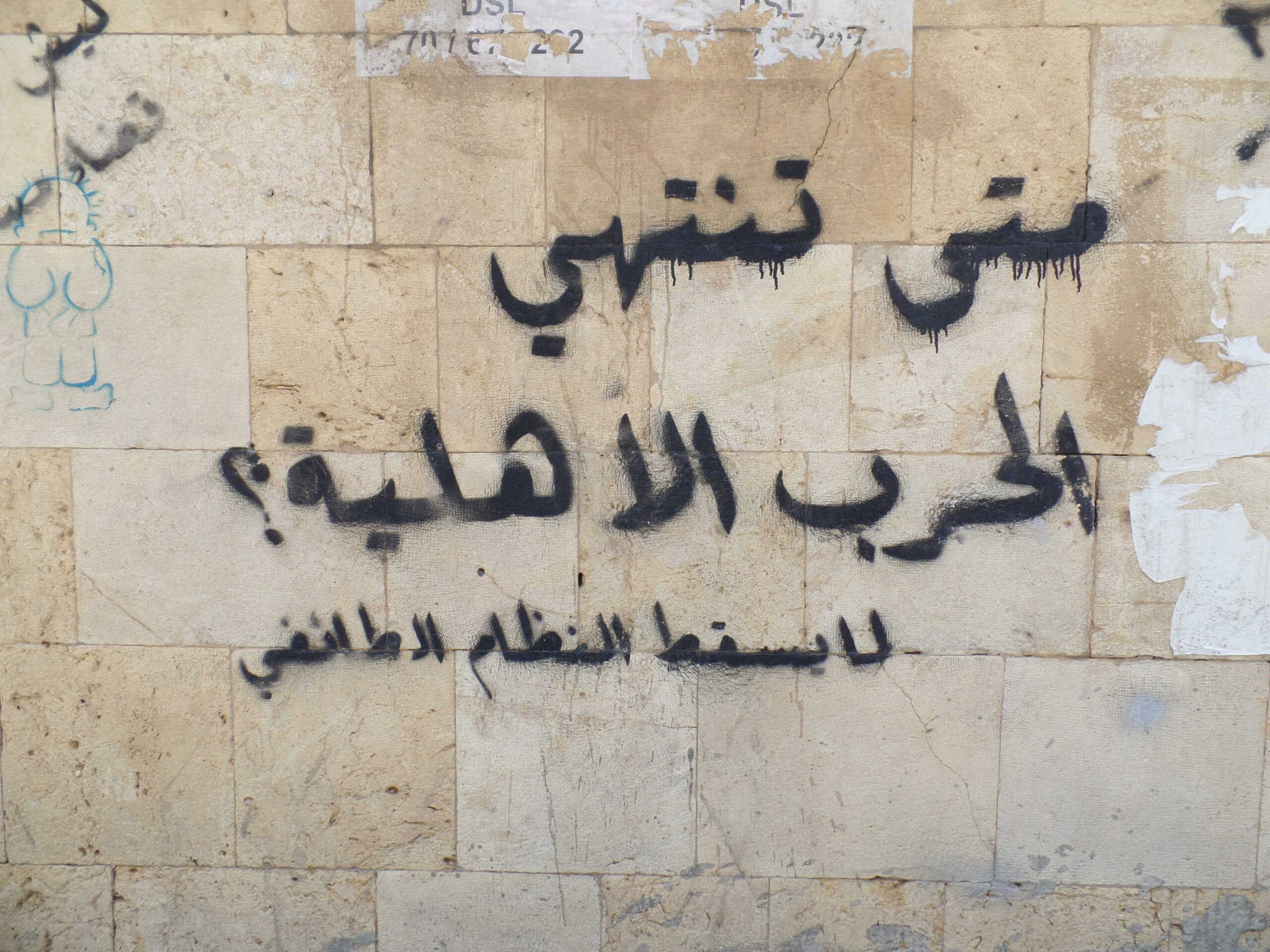

I really like this question actually, because I believe the Lebanese Civil War shows up, in both direct and indirect ways in “post-war” graffiti. So, for example, there are stencils that directly reference the Lebanese Civil War and the sectarian system- There are some stencils that ask, “Why is the electricity still out?– because of the sectarian system?” Or even, “When will the civil war end? –Well, when the sectarian system is ousted.” So these directly address the Civil War, and they invite us to consider that there is still political precariousness in Lebanon and that the Civil War has not truly ended in the real sense of the word, because the sectarian system is still enduring, but other stencils for me may not directly reference the war, but they still invoke war and violence. So, for example, there are playful stencils that feature little bombs shaped stencils or images of people kicking bombs instead of soccer balls. And, visual studies scholar Tanya Saleh who I cite in the book, talks about these bomb-shaped stencils, and she tells us that they were first spotted in the aftermath of the assassination of former Prime Minister Hariri. And, so for Saleh, these stencils kept fresh the tragedy in everyone’s minds, reminding people that violence in post-war Lebanon is still there. I agree with her and as I said, though, sometimes it’s indirect. So even like the murals of beloved singers and poets and musicians, when you interview the artists, or when you read some of their interviews, they very clearly indicate that part of the inspiration is the fact that they wanted to replace the posters of political leaders who thrived during the Lebanese Civil War. And so, this demonstrates how the Civil War is sneaky. It keeps showing up in different ways.

When Will The Civil War End? Stencil. Photo by Nadine Sinno and William Taggart.

Maybe we can come back to the title of the book, A War of Colors. Is that why you titled this as a book as well, or what did you mean by the title exactly?

Yes. I really couldn’t help but ultimately choose this title because it kept coming to my head every time I tried to think of different titles. I really did consider other titles that were just more academic and less vivacious, I think. I had first used the first part of the title, “A War of Colors,” in the journal article that I published back in 2017. I thought it was just really suitable for the book because it spoke to the book’s broader theme and its general ethos. And this is directly taken out of a graffiti by EpS and M3alim, which features a man actually wearing military camouflage and standing in front of the words “Harb Alwan”, in Arabic, which means a war of colors. And so, for me, it epitomized the dynamics of civic engagement that is rooted in competitive graffiti-making.

The title does not refer to any specific war, but rather to this ongoing alternative kind of war. The mural itself heralds an urban war of a different order. Maybe we can think about it as a battle for Beirut’s ornamentation through the production of street art. These warriors are armed with brushes and spray cans, and they strive to outdo one another by creating colorful street art. But they also challenge our minds in ways that are not just focused on aesthetics necessarily. So I liked the idea of using that title again, allowing, basically, the graffiti pieces to tell the story even through the title. Using the same logic, actually, each of the chapters also begins with a direct caption from one of the graffiti pieces.

Can you maybe characterize the landscape of the street art artists? Like are they mostly men or are there many female artists as well?

I would say it was predominantly male, particularly when I started first taking the pictures in 2014. But I think as the years went by, more women were taking to the streets. And that became clear with the graffiti of the Lebanese protests of 2019 and 2020. That’s when a lot more women took to the streets. That’s also when a lot of non-professional people took to the streets to also participate in creating graffiti. But women’s issues were also at their peak during that difficult time. And you see in the chapter on animating resistance that a lot of the street art was being done by new actors, particularly women from different art collectives or activists who were very excited to be part of this journey.

You write about this in the book as well, while you were in Beirut and took photos of the street art. How difficult was it for you to take them, and what other difficulties did you come across while working on the book in general?

As I say in the book, some days were really smooth sailing while others were a bit more challenging, depending on the area or, or the political moment in which I was taking pictures or even the people who were involved at different times. So, for the most part, I would say I was very fortunate in that I did not experience the type of harassment or surveillance that you might find in other Arab countries that are more authoritarian or where graffiti is unquestionably considered illegal. We don’t have that same sort of surveillance in Lebanon. So usually beyond pausing to check which graffiti I was looking at, most people ignored me and my husband and just went about their daily business. But there were times when members of the Lebanese army or the police would stop and, and ask, “Who are you affiliated with? Why are you taking these pictures?” Usually, I would say this is for my academic research, and it was fine, but at the same time, we were instructed not to take pictures in heavily policed areas that were considered security zones or potential targets of bombing. For example, you can’t take pictures near mosques or churches or headquarters of militias or homes of political leaders. In those areas, there’s definitely increased security and scrutiny actually. And, so, occasionally we were stopped and interrogated by either the police or members of militias. And I think I mentioned this in the book, that in one incident, we got questioned by neighborhood vigilantes who were not in uniform, and they started asking us, “Do you have a permit?” And of course, we did not have a permit to take pictures. And, there was a bit of going back and forth and me promising to delete the picture and promising not to come back to the neighborhood. And that was fine. It wasn’t pleasant, but it could have been worse. And I realized that when I was with my girlfriend, it was easier sometimes because I always say that the damsel in distress situation can have its advantages in a patriarchal society.

So, people either want to help you or let you get away with stuff. So sometimes that worked and people left me alone. With the more sensitive type of graffiti, it was harder. I also mentioned in the acknowledgments that my brother offered to take me on his moped to take pictures of the graffiti that was more political or more obscene and being on a moped allowed us to get in and out of neighborhoods more easily. It helped.

Phat2 tag. Photo by Nadine Sinno and William Taggart.

How did you choose the material that you wanted to put in the book? And you took so many pictures, how hard was it for you to leave some of them out, and what kind of other resources did you use for your research?

One more thing to add regarding the issue of difficulties I faced: I was revisiting a topic that emotionally affected me personally. At times, things reminded me of the traumatic Civil War, or I was dealing with material related to Lebanon’s economic collapse and the corrupt banking system and all this. So that was difficult for me emotionally. And then the selection process itself, as you rightly asked, is difficult. How do you choose what to include, what to exclude? And that process really took place over months, if, if not even years. In the end, I looked at how the data presented itself and, and how it came together organically. That is how each chapter took form.

Also, there wasn’t just one point in time where I said, “Okay, these pictures are in, these pictures are out.” Rather, I wrote a lot and I initially tackled a lot more images and included analysis of them, but some did not make it to the book. And, I think that’s the nature of scholarly work. I’m not special. I had mentors also look at the manuscript and help me determine what needed to stay and what had to be condensed because you need fresh eyes sometimes because you’re so immersed in the material, and I was feeling protective of every image and every paragraph, right? So what I tried to ultimately do is to include as many diverse artifacts as I could, and particularly focus on those that were sufficiently representative of the larger picture or the landscape as you refer to it.

Once you see recurring themes, discourses and conversations, you kind of know, okay, these are topics that really need to be included, alongside their corresponding graffiti pieces. In terms of other resources, I looked at Lebanese newspapers in Arabic, and I looked at websites. I’m not very good with social media, so thanks to research grants, I was able to hire students who had a better read on social media. They would say, “You need to check this out” if something caught their attention. Of course, also as an academic, you always want to make sure you contextualize your work. So, I wanted to learn more about the wartime graffiti. I’m very grateful for Maria Chakhtoura’s book which tackles the graffiti of the civil war. I also wanted to learn about wartime political posters because those came before the graffiti that I’m talking about. And it’s important to discuss not only background but genealogy and how things connect to one another. I’m very grateful for the amazing work of visual scholars who have worked on Lebanese political posters, such as Zeina Maasri, whose work focuses on wartime political posters. I also looked at Palestinian and Egyptian graffiti because it’s good to make connections. As a comparative literature person, you always want to look at convergences and divergences among different cultural practices and across periods.

Nadine Sinno: Interviewed by Tugrul Mende.

Nadine A. Sinno is an associate professor of Arabic and director of the Arabic Program at Virginia Tech, as well as a literary translator. She is the co-author of Constructions of Masculinity in the Middle East and North Africa.

Tugrul Mende holds an M.A in Arabic Studies. He is based in Berlin as a project coordinator and independent researcher.