Présenté au festival de Cannes 2022 dans la section « Un certain regard », Le bleu du caftan, le nouveau film de la réalisatrice marocaine Maryam Touzani, est sorti en salles en France au printemps 2023 après avoir été diffusé au Maroc en février (avec des restrictions d’âge). À Cannes, il a remporté le prestigieux prix de la Critique et a accompli depuis un beau parcours, glanant de nombreux prix ainsi qu’une nomination aux Oscars.

C’est une œuvre qui fera assurément date dans le cinéma arabe, à la fois pour sa mise en scène parfaitement maîtrisée et pour sa façon audacieuse d’aborder le thème de l’homosexualité. La réalisatrice a élaboré le scénario et les dialogues avec Nabil Ayouch qui est également producteur, le couple (ils sont mariés à la ville) ayant travaillé selon un schéma de collaboration déjà éprouvé sur leurs films précédents (Adam pour elle, Much loved pour lui).

Le film frappe d’emblée par son utilisation de l’espace, se déroulant en grande partie dans le volume confiné d’une échoppe de broderie au cœur de la médina de Salé, qui elle-même forme un labyrinthe de venelles tortueuses et intriquées.

C’est là que Halim (Saleh Bakri) et sa femme Mina (Lubna Azabal) confectionnent au fil des ans des caftans destinés à des clientes de la haute société marocaine. Même s’ils se sont bien réparti les rôles – il est le maalem (le maître-artisan) qui travaille patiemment les étoffes, tandis qu’elle gère les relations avec la clientèle et les fournisseurs, négociant fermement les prix et les délais, l’endroit peine à les contenir. Cette exiguïté conditionne les comportements (impossible de trouver une quelconque intimité) et les déplacements (il faut s’effacer pour laisser place à l’autre). La même contrainte vaut pour leur appartement situé non loin de là, qui paraît ne comporter qu’une chambre à coucher et un renfoncement où Halim se réfugie pour fumer. Tous ces espaces, éclairés par le jour naturel ou par des chandelles, donnent au film sa photographie somptueuse, toute de clairs-obscurs.

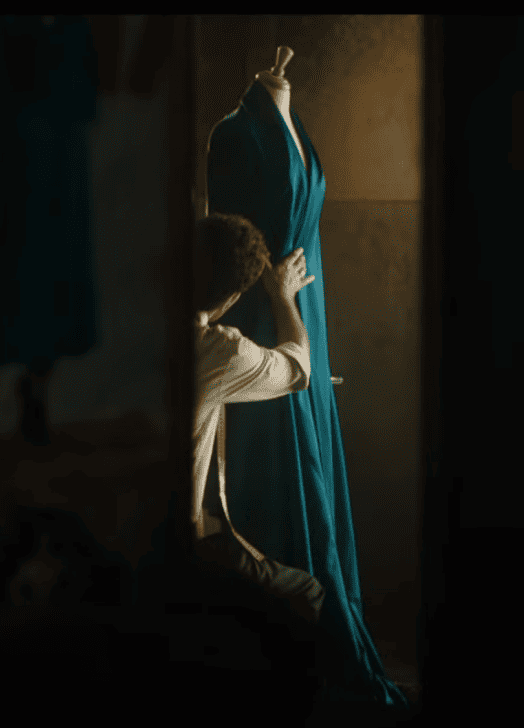

Dans cet atelier, on travaille exclusivement à la main, avec une exigence de qualité qui fait tout le prix de ces pièces uniques. Le film est une véritable ode à cet art exigeant et minutieux, dont chaque étape est importante : le choix des étoffes, appréciées dans leurs teintes, leurs textures et leur souplesse, la beauté du fil d’or qu’on doit enrouler et dérouler autour des bobines… C’est un art qui toutefois est en train de disparaître. A une femme qui apporte un somptueux caftan confectionné selon des techniques qui n’ont plus cours, Halim répond rêveusement : « J’ai connu un artisan qui les faisait, il avait appris auprès des Juifs… ». Cependant, cette exigence a un prix, et elle impose des délais de livraison extrêmement longs, d’autant que Halim est seul face à l’immensité de la tâche : chaque caftan est travaillé sur mesure, brodé selon les exigences de la cliente et en fonction de l’occasion où il sera porté.

D’où l’idée de faire venir un apprenti : ce sera Youssef (Ayoub Missioui), dont on assiste au recrutement par le couple. Malgré le talent naturel du jeune homme et sa bonne volonté évidente, Mina se montre circonspecte, persuadée qu’il finira par partir comme tant d’autres avant lui qui n’ont pas eu la patience ou la rigueur pour ce travail ingrat et ont préféré devenir livreurs pour épouser le rythme de l’époque. Halim, quant à lui, veut y croire, Youssef semble être d’une autre trempe et mû par un vrai désir d’apprendre. Mais peut-être y a-t-il autre chose, et le scepticisme de Mina ne tarde pas à se muer en franche hostilité…

L’homosexualité de Halim nous a été révélée d’emblée, d’abord indirectement dans son entière passivité au lit (on voit Mina le prendre dans une étreinte qu’il subit sans plaisir), puis plus explicitement lors d’une scène de hammam, filmée comme un rituel : là encore, la mise en scène joue avec virtuosité de l’organisation des espaces, plus amples mais rendus oppressants par la moiteur étouffante qui baigne les corridors, les salles communes et les cabines individuelles.

L’arrivée de Youssef dans la vie du couple, qui coïncide avec l’aggravation de la maladie de Mina, agit comme un catalyseur. Une timide romance entre Halim et Youssef, à peine suggérée par un rapprochement, une étreinte ou une tâche accomplie en commun, permet une échappée hors du sexe sans amour pris à la sauvette dans les espaces privés du hammam. La douceur de leur caractère les unit aussi dans une complicité amusée face à la fermeté affichée de Mina.

L’histoire se lit aussi dans les corps des personnages, en particulier sur leurs dos qui révèlent leur force ou leurs faiblesses. Le dos vigoureux et bronzé de Youssef quand il se change dans l’échoppe, s’attirant les regards de Halim et les remontrances de Mina (« La prochaine fois tu te changes chez toi, on n’a pas le temps pour ça. »). Le dos osseux et hâve de Mina, sur lequel la maladie exerce son emprise – elle n’est plus capable de manger autre chose que les quartiers de mandarines que Halim lui prépare amoureusement. Celui enfin de Halim, encore solide mais maculé de taches de vieillesse.

Le film suit son lent cheminement pour nous montrer les liens qui s’établissent entre les trois protagonistes. Mina résiste tant bien que mal à la maladie, tenant à rester jusqu’au bout l’épouse vaillante, malgré les protestations de Halim dont l’affection pour sa femme transpire dans chacun de ses gestes et qui la supplie de se ménager. Sa méfiance initiale envers Youssef se mue bientôt en indulgence – n’est-ce pas celui qui apporte à Halim la vitalité qu’elle n’est plus capable de lui donner ? Malgré sa conscience de le perdre, elle conserve à son époux sa pleine estime et le défend face aux exigences absurdes des clientes, qu’elle oblige à se plier au rythme du maalem – c’est lui le patron qui dicte le calendrier. Quand viendra le temps des aveux, elle le libérera de sa honte en affirmant qu’elle ne connaît pas plus noble que lui, lui restituant d’une certaine manière sa dignité d’homme.

Cette cellule familiale et amoureuse se soude progressivement contre les intrusions extérieures, vécues comme des agressions. Les clientes pressées, qui voudraient la qualité du travail fait main mais la vitesse des « machines », et qui, face à un délai jugé trop long, agitent la menace d’aller à la concurrence. Le fameux caftan bleu qui donne son titre au film concentre les attentes : la cliente vient sans cesse s’enquérir de l’avancement des travaux, quand une autre se dit prête à payer davantage pour l’arracher à sa commanditaire initiale. Mais les intrusions sont également le fait des voisines qui passent leur temps à épier et se piquent de régenter la médina : l’une d’elles hurle sur le barbier de rue pour qu’il baisse le son de sa radiocassette – le même son sur lequel danseront les trois protagonistes dans une des plus belles scènes du film.

La réalisatrice, inspirée par une rencontre faite il y a quelques années dans la médina, déclare avoir voulu ouvrir le débat sur la question de l’homosexualité. Nul doute que ce film tout en délicatesse, avec son choix avisé de ne pas heurter le public à travers des scènes trop explicites et son jeu d’acteurs tout en nuances, y contribuera. Mais c’est peut-être du finale en forme de tragédie que vient la véritable subversion, quand Halim décide, passant outre la tradition, de donner à sa femme le seul hommage qu’il juge digne d’elle…

Khaled Osman

A Romance Sewn With Gold Thread: A Review of “The Blue Kaftan.”

Presented at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival in the “Un Certain Regard” section, The Blue Caftan, a film by Moroccan director Maryam Touzani, was released in theaters in France in Spring 2023 after having been released in Morocco in February (with age restrictions). In Cannes, the movie won the prestigious Critics’ Prize and has since made a great journey, winning numerous awards and an Oscar nomination.

It is a work that will certainly be a milestone in Arab cinema, both for its perfectly mastered staging and for its audacious way of tackling the theme of homosexuality. The director developed the script and the dialogues with Nabil Ayouch, who is also the movie producer, the couple (they are married in real life) have worked according to a collaboration pattern already experienced and proven by their previous films (Adam for her, Much Loved for him).

The film is immediately striking for its use of space, taking place largely in the confined volume of an embroidery shop in the heart of the medina of Salé, which itself forms a labyrinth of tortuous and intricate alleys.

Over the years, Halim (Saleh Bakri) and his wife Mina (Lubna Azabal) have been making kaftans for Moroccan high-society clients. Even though they have divided up the roles well – he is the maalem (master craftsman) who patiently works with the fabrics, while she manages relations with customers and suppliers, firmly negotiating prices and deadlines – the small place struggles to contain them. This cramped space conditions their behaviour (it is impossible to find any intimacy) and movement (you have to step aside to make room for the other). The same constraint applies to their apartment located nearby, which appears to have only one bedroom and a recess where Halim takes refuge to smoke. All these spaces, lit by natural light or by candles, give the film its sumptuous photography, all in chiaroscuro.

In this workshop, they work exclusively by hand, with a very high standard of quality, high value, and uniqueness of these pieces. The film is a true ode to this demanding and meticulous art, each step of which is important: the choice of fabrics, appreciated in their shades, textures, and suppleness, the beauty of the gold thread that must be wound and unwound around the spools… But it is also an art that is disappearing. To a woman who brings a sumptuous kaftan made using techniques that are no longer in use, Halim replies dreamily: “I knew a craftsman who made them, he had learned from the Jews… I am not sure.” However, this high standard comes at a price, and it imposes extremely long delivery times, especially since Halim copes by himself with the immensity of the task. Each kaftan is custom-made, and embroidered according to the client’s specific needs and according to the occasion on which it will be worn.

Hence the idea of bringing in an apprentice: Youssef (Ayoub Missioui), with the film showing his recruitment by the couple in detail. Despite the young man’s natural talent and obvious goodwill, Mina is cautious, convinced that he will end up leaving like so many others before him who did not have the patience or rigor for this thankless job and preferred to become delivery drivers to keep up with the rhythm of the times. Halim, on the other hand, wants to believe he will stay, aware that Youssef seems to be of a different caliber and driven by a real desire to learn. But perhaps there is something else, and Mina’s skepticism soon turns into outright hostility…

Halim’s homosexuality was revealed to us from the outset, first indirectly in his complete passivity in bed (we see Mina taking him in an embrace that he receives without pleasure), then more explicitly during a hammam (public bath) scene, filmed as a ritual: here again, the staging plays with virtuosity on the organization of the spaces, which are larger but made oppressive by the suffocating humidity that bathes the corridors, common rooms and individual cabins.

Youssef’s arrival in the couple’s life, which coincides with the worsening of Mina’s illness, acts as a catalyst. A timid romance between Halim and Youssef, barely hinted at by a rapprochement, an embrace, or a task accomplished together, allows an escape from loveless sex taken on the spur of the moment in the private spaces of the hammam. The sweetness of their character also unites them in amused complicity in the face of Mina’s displayed firmness.

The story can also be read in the characters’ bodies, especially on their backs which reveal their strengths or weaknesses. Youssef’s strong, tanned back as he changes in the shop, drawing Halim’s glances and Mina’s remonstrance (“Next time you change at home, we don’t have time for that”). Mina’s bony, haggard back, on which the disease exerts its hold – she is no longer able to eat anything other than the mandarin wedges that Halim lovingly prepares for her. Finally, Halim’s back is still solid but stained with age spots.

The film follows its slow path to show us the bonds established between the three protagonists. Mina resists the disease as best she can, insisting on remaining the valiant wife until the end, despite the protests of Halim, whose affection for his wife transpires in his every gesture and who begs her to take it easy. Her initial distrust of Youssef soon turns into indulgence – isn’t he the one who gives Halim the impetus she is no longer able to give him? Despite her awareness of losing him, she protects her husband’s right to respect and defends him against the absurd demands of the clients, whom she forces to comply with the rhythm of the maalem – he is the boss who dictates the schedule. When the time comes to confess, she will free him from his shame by affirming that she knows no nobler than him, in a way restoring to him his dignity as a man.

This family and love unit gradually welds against external intrusions, resented as aggressions: Customers in a hurry, who would like the quality of the handmade work but the speed of the “machines,” and who faced with a delay deemed too long, threaten to go to the competition. The famous blue caftan that gives the film its title is highly coveted. The client who ordered it constantly comes to inquire about the progress of the work, while another says she is ready to pay more to snatch it from its initial orderer. But the intrusions also come from the neighbours who spend their time spying and taking pride in ruling the medina: one of them yells at the street barber to turn down the volume of his boombox – the same sound to which the three protagonists will dance in one of the most beautiful scenes of the film.

The director, inspired by an encounter she had a few years ago in the medina, declared she wanted to open the debate on the issue of homosexuality. There is no doubt that this delicate film, with its wise choice not to offend the audience through overly explicit scenes and its nuanced acting, will contribute to this. But the ultimate subversion perhaps comes from the finale, staged like a tragedy, when Halim decides, ignoring tradition, to give his wife the only tribute he deems worthy of her…

Khaled Osman

Editor’s note: To honor the writer’s preferred language for this piece, it has been published in French, with an AI-generated English translation. Edits to the AI-document were discussed with the author to ensure fidelity to the meaning of the original text.