by Khaled Al-Qershali

After October 2023, I followed the news only from behind my phone screen, hesitant to write or share anything that’s happening around me.

After being displaced, my friend Khaled used to urge me and insist that I should start writing.

“If you don’t feel like writing for yourself, at least write about others and convey other people’s stories in Gaza,” Khaled would tell me.

But I didn’t listen despite having strong English and many things to share.

I enrolled in English literature in 2020 at the Islamic University of Gaza despite my parents wanting me to study nursing.

I thought learning English would enable me to learn new cultures of the world using the world in its most dominant language.

Khaled kept urging me to start writing, but I always refused, blaming the circumstances I was having. There was not any internet network where I was displaced and the electricity was out.

When Israel assassinated Dr. Refaat Alareer on 6 December 2023, I was beyond devastated. Despite the circumstances, I did not want Dr. Refaat’s voice to fade.

I reached out to Khaled and asked him to help me publish a tribute piece about Dr. Refaat, honoring his impact on me and my personality.

From that point on, I began writing—reading countless articles every day and seeking Khaled’s help to publish the truth of what was happening.

Although the occupation killed Dr. Refaat, I wanted to carry on his voice. I wanted to be like him—amplifying the truth he lived and died for.

I believed that if people around the world truly understood what was happening here, something would change—that the genocide would end soon. Very soon.

Writing was never easy. I’m the eldest son in my family, with a younger brother and sister. Most of my daily routine revolved around taking care of them while my father went to work as a pharmacist at Al-Aqsa Hospital.

Each morning, I would spend more than an hour filling parable water in our six jerry cans and 120 liters tank of water for washing.

I would then head to the market to look for anything we could afford. Most days, I came back with a few pieces of vegetables—just like every other displaced person.

Hygiene, medicine, cooking gas and even electricity were scarce. But somehow life continued. Basic human rights—things that should be easily accessible—had become distant, difficult luxuries.

Still, neither did I give up on writing nor on continuing my bachelor’s degree through online classes whenever I could.

I believed in the power of the English language—as a tool to tell our story, to help the world understand our struggle.

By the approaching of the so-called ceasefire 19 January 2025, although people were enjoying it at first, but soon after that joy vanished. No one in the Strip did not lose a friend or a family member.

Mohmmed Hamo and Abdullah Al-Khaldi were two close friends of mine whom I had lost on 24 November 2023.

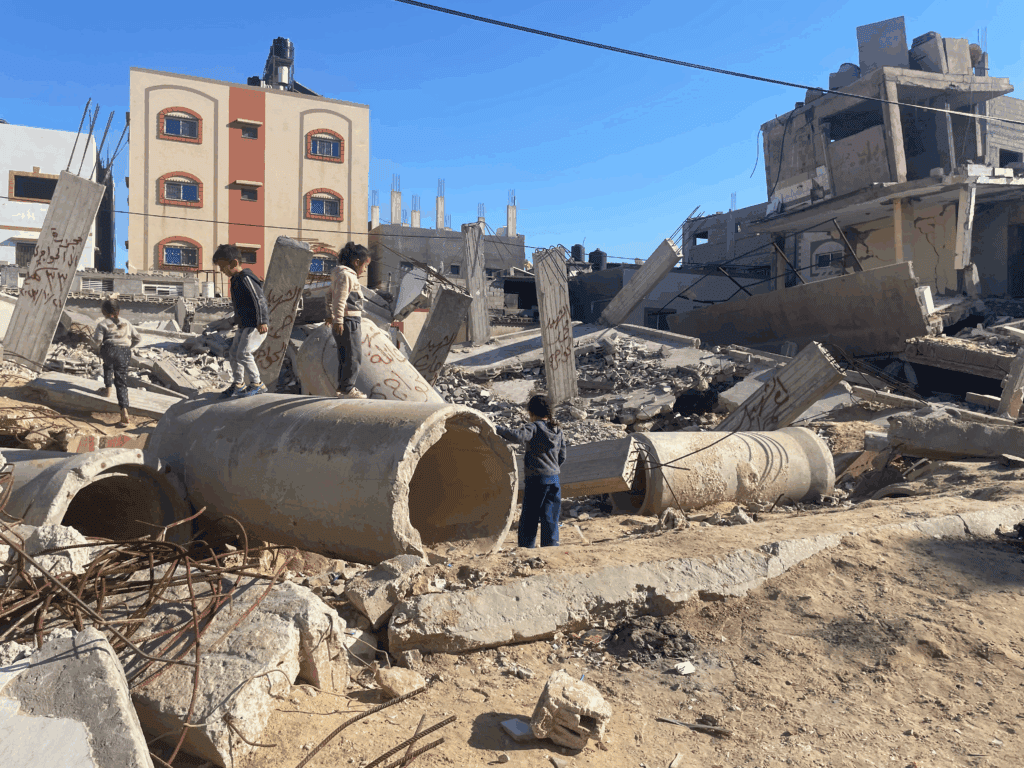

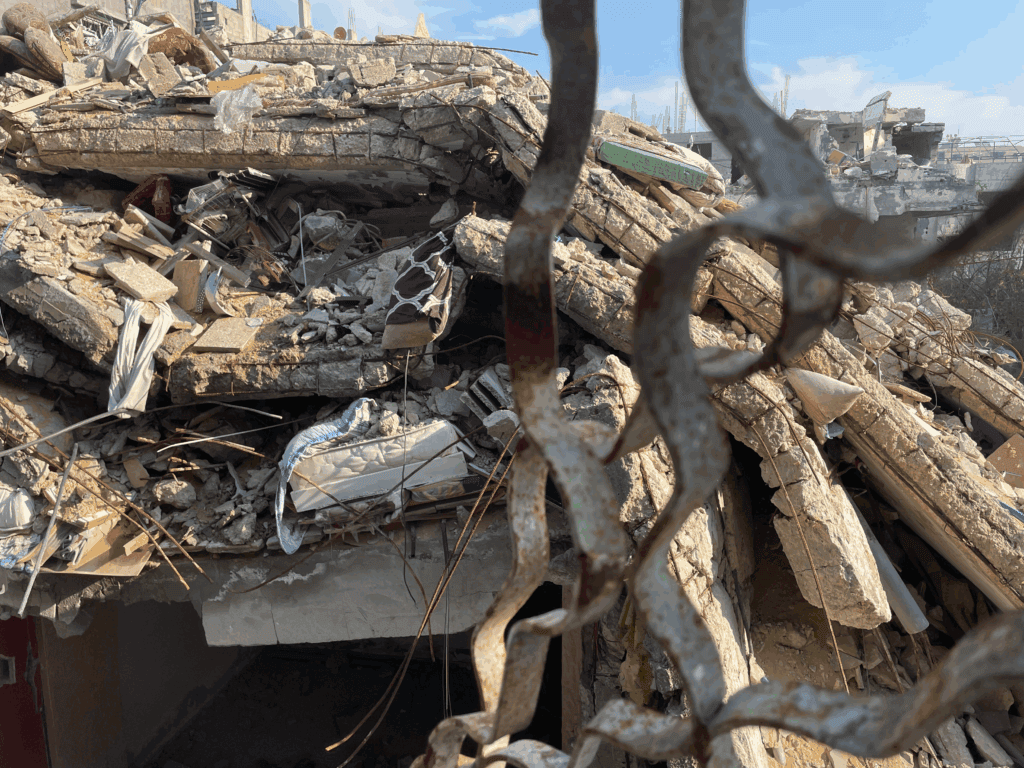

When the road between the northern and southern parts of Gaza was opened on 27 January 2025, I had the chance to return, but there were nothing to return to. My home was destroyed, my university was bulldozed, and my friend’s body still under the rubble.

On 18 March, the Israeli occupation shattered the ceasefire agreement and my life was upended – again.

My daily routine returned—but even worse. There’s nothing to find in the market as the crossing border was closed two weeks earlier on 2 March.

When available, prices are unbearable. A packet of coffee that once cost 15 now sells for 40. Cooking oil went from 8 to 45. Sugar, from 6 to 80.

Vegetables, if found, are sold at outrageous prices and can’t even be stored.

We had managed to save some wheat, rice, and cheese packets, but they ran out—and we don’t know what to do.

I could not even find a stable electricity source to charge my computer—to write, work, study, or simply read. Charging points had become dangerous, potential targets at any moment.

This is all in southern Gaza, where I am now—and where conditions are still considered better.

But my relatives in the north in al-Nasser neighborhood can barely find anything to buy at all.

They can’t store food as well. They’re too afraid to—worried that if they do, they’ll be forced to evacuate again, leaving it all behind.

My uncle had stored a bit of food and a gas tank in case of further shortages. They weren’t given any evacuation order.

On 3 April, their house was bombed without warning. It collapsed on top of them. They remained trapped under the rubble for hours before neighbors managed to pull them out.

Maybe I can’t charge my computer—but at least I still have it. My cousin’s computer is still buried under the rubble. It’s probably destroyed.

My uncle’s family were then taken to Al Ahli Arab Hospital for treatment and shelter. Thank God we convinced them to flee again to the south — had they stayed, they might have been killed in the latest attack on the hospital.

On 7 April, my friend Khaled sent me a message, casually asking if it was cold where I am.

Although we are in spring, the weather was truly freezing that night.

I couldn’t tell Khaled that I gave my blanket with my cousin because everything they had was under the rubble.

Instead, I replied, “No, it is warm inside the tent and I have my fleece blanket.”

I lied, not because I wanted to hide the truth, but because I knew Khaled was already burdened—fighting his illness, carrying more than enough on his shoulders. I didn’t want to add to it.

But Khaled’s reply caught me off guard.

He wrote, “I’m freezing too. I put on some simple clothes and went outside—just to feel, for a moment, what you’re going through right now.”

I told him to stop the nonsense and go back inside—only to receive even more devastating news.

“Pray for me,” he wrote. “Doctors now suspect I might have another type of malignant cancer—melanoma.”

Khaled had already been diagnosed with blood cancer in October 2023 and travelled to Jordan to receive chemotherapy.

I wanted so badly to call him, to offer some comfort—even if just through words. But the place I was sleeping in had other limits.

I was cramped in a corner beside my father and other family members.

One call would have woken everyone.

I prayed for him and told him to stay strong. But later that night I couldn’t stop thinking. I lay awake for hours, trying to understand why all of this was happening.

Sleep eventually came, but the same question stayed — why is all of this still happening?

On 12 April, it was my turn to stay overnight at the hospital and care for my uncle and cousin. In the middle of the night, the Israeli army bombed a tent inside the hospital grounds.

Just three days earlier, the occupation had targeted another tent in the same hospital.

Another question erupted within me: Why am I even writing and to whom?

We have documented, recorded, photographed, reported, broadcasted, exposed, narrated, shared and bore witness to every atrocity happening on the ground.

The whole world watched as we in Gaza were shot, maimed, burned alive, buried beneath rubble, extracted from graves, starved, displaced, amputated without anesthesia, left to die without medicine, bombed in hospitals, massacred in schools and denied even the dignity of mourning.

We were crushed under the weight of our homes, bombed in our sleep, shot as we fled, starved in UN shelters, suffocated under tents and silenced while calling for help.

On May 2025, the Israeli occupation came with new idea to kill more Palestinians.

The Israeli occupation created Gaza Humanitarian Foundation to distribute aid hazardously by dropping aid supplies in unsafe zones where desperate civilians became easy targets.

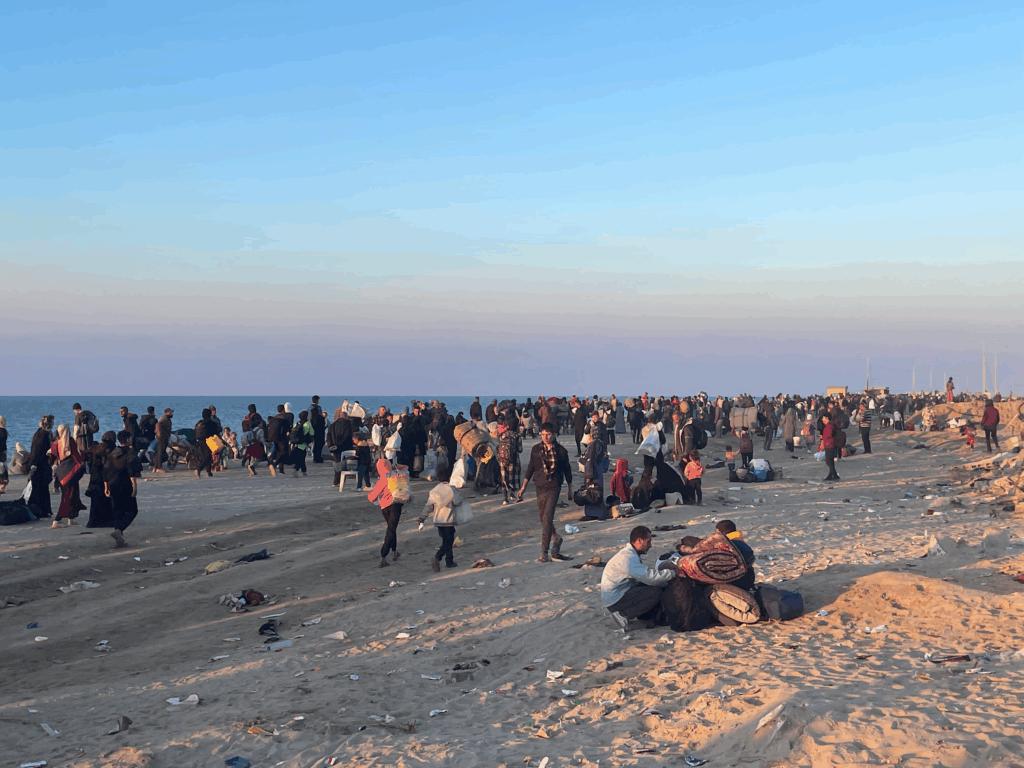

After seeing many neighbours and relatives returning with aid packages, although they said that they had seen death there, I went.

All food essentials were out of the market. I had to go hoping I might return with something.

On 24 June, I went to Nitzarim distributing point, but instead of aid, I returned with fear as the most that was distributed was death.

Israel bombed ambulances, targeted aid workers, shelled bakeries and water tanks, turned hospitals into graveyards and wiped out entire families in a single airstrike.

We were denied food, water, and medicine. We were left to dig mass graves with bare hands. Mothers wrote their children’s names on their legs in case their bodies were never identified.

Israel bombed us while evacuating, shot us while searching for bread, sniped at children playing near tents, and erased entire generations in seconds.

Our voices were buried beneath collapsed buildings, our stories erased from headlines, our names reduced to numbers—yet we kept writing, filming, shouting, refusing to disappear.

We were hunted in our streets, in our shelters, in our schools. No space was safe. No pause was real. No ceasefire was honored.

The genocide never stopped, and Israel kept bombing wherever, whenever and whatever it desired. Israel still bombs Gaza with full immunity because the whole world allows so.

The Israeli occupation claims that they are negotiating in a ceasefire, but that is the biggest lie.

They had negotiated for weeks and still negotiating everyday without any results. Thousands of innocent civilians are being killed while the Israeli occupation still negotiating for a ceasefire.

This is not state terrorism, this is not a two-sided war, this is even far beyond the definition of genocide.

Khaled Al-Qershali is an English graduate working as a journalist in Gaza.