“We are fighting human animals.” — Yoav Gallant, Israeli Defense Minister, October 2023

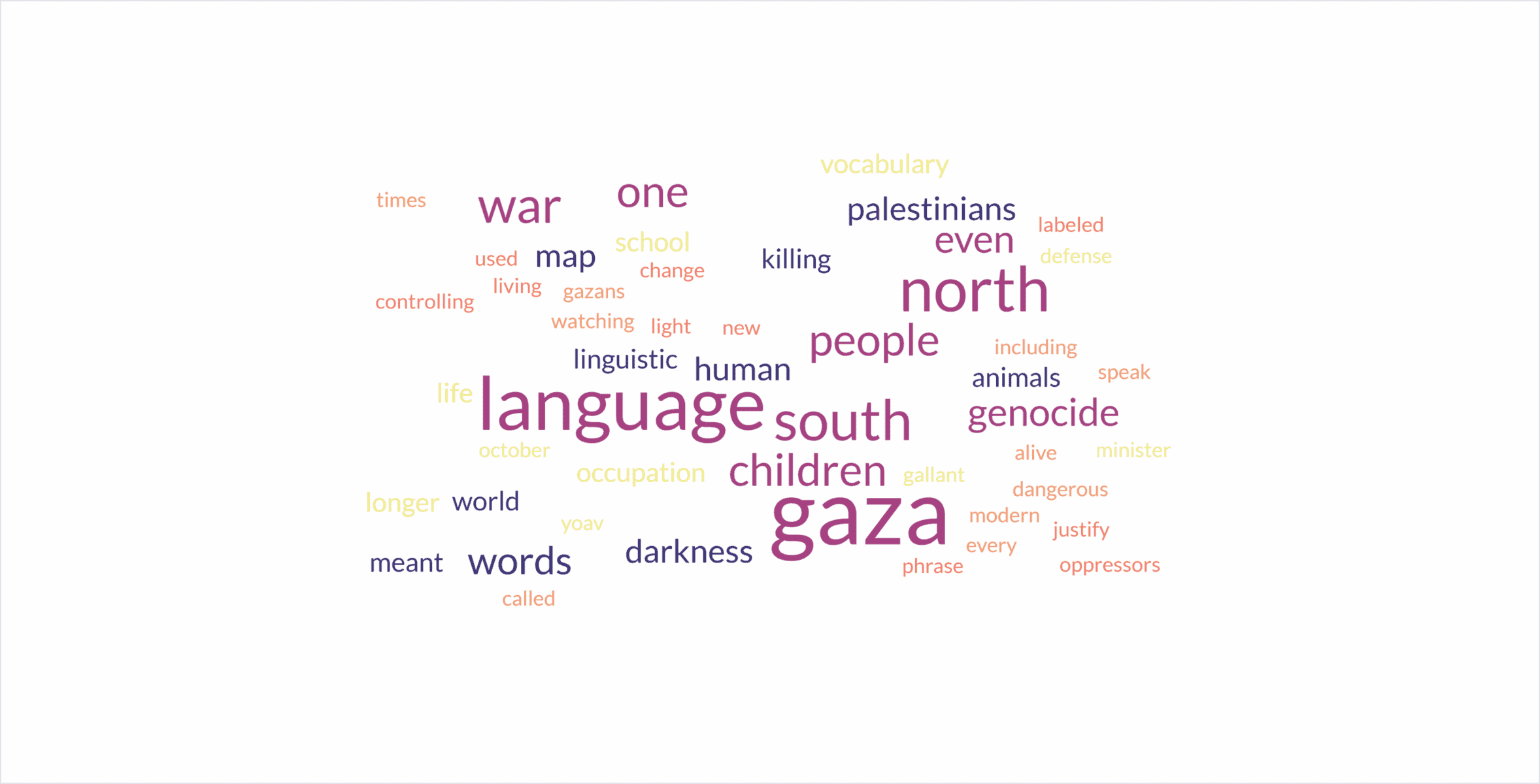

Since October 7, 2023, the world has watched Gaza burn alive under one of the most brutal genocides of modern times. But what many observers fail to realize is that this is not just a war of bombs and bullets. It is also a war on language — a linguistic invasion far more dangerous than one might think.

This genocide is not merely about killing as many Gazans as possible. It is an attempt to erase us on every level — including how we speak, how we name ourselves, how we dream, and even how we describe our pain.

“Human Animals” – The Language of Dehumanization

When Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant called Palestinians “human animals,” it was not a haphazard description that came from nowhere. It was a deliberate, calculated phrase meant to justify the unjustifiable: injustice and mass killing. By stripping a people of their humanity in words, the Israeli occupation prepares the world to accept their erasure in action — and, in many ways, to occupy the global perception of Gaza and its people.

I have always said: words are dangerous — they can change and alter narratives in favor of the oppressors.

This tactic is not new. Throughout history, oppressors have used animalistic language to legitimize violence and normalize it: African slaves in the United States were called “beasts”; Jews in Nazi Germany were referred to as “vermin”; Black Americans were labeled “brutes.” Palestinians are now enduring the same linguistic weaponization — because once a people is declared “less than human,” their suffering becomes easy to ignore and to be marginalized.

Children of Darkness vs. Children of Light

Another chilling phrase used by Israeli officials describes this war as a battle between “the children of light” (Israelis) and “the children of darkness” (Palestinians). And they did so in order to justify the killing our of babies. This language evokes a religious war — casting one side as divinely righteous and the other as evil incarnate.

It’s a narrative that echoes dystopian literature and fascist ideologies. We are literally living under the shadow of George Orwell’s 1984, where controlling language was key to

controlling thought. In Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, entire regions were labeled as primitive and dark — justifying colonization slaughter, and imperialism . Gaza has become the modern “heart of darkness” in the eyes of the all colonizers across the world — where genocide is romanticized.

Gazan Language: From Life to Survival

Before the genocide, Gazans spoke the language of the living. People discussed school, weddings, careers, dreams, love, and hope. The vocabulary was wide and full of possibility.

Now? The daily lexicon has been reduced to:

“Is there food today?”

“Do we have clean water?”

“How many martyrs?”

“Is there a ceasefire?”

“Did aid reach our area?”

“How long will we survive?”

The genocide has not only killed people — it has killed the very words that gave meaning to their lives. Children no longer learn vocabulary from school books — they no longer even go to school. More significantly, they now speak the language of war without being fully aware of it.

The other day, I was watching my relative’s children playing a car game, and one of them said, “See my car! It’s moving like a rocket!”

Even the way people identify themselves has changed. Gaza is officially divided into four governorates: Gaza, North Gaza, Middle, and South (including Khan Younis and Rafah). But during the early days of the genocide, the Israeli military published a map instructing civilians to evacuate “from north to south.”

By “north,” they meant North Gaza and Gaza City; by “south,” they meant the Middle Area and beyond. The map erased our official divisions — and, tragically, that new framing is forced to enter into our language. Since that evacuation map appeared, even Palestinians have begun to echo its labels. Scrolling through social-media threads, I now see casual barbs like:

“You’re from the north, I’m from the south.”

The first time I read a comment like that, two strangers in a public group were arguing. One, still trapped in Gaza City, scolded the other for being “safe” in the south—as if displacement were a choice. He insisted that the north suffers heavier bombardment “most of the time.”

A few lines later I saw:

“Aid reached the south but not the north.”

“The famine in the north is worse than in the south.”

Envy slips in, resentment takes root—and no one pauses to ask who taught us these words.

Beyond Gaza’s four governorates, we now talk only of north and south—terms invented by the Israeli army, not by us. Their map has done its job: turning ordinary speech into a fault line.

It entered our language like poison in water.

Language Under Occupation

Words are not free in Gaza. Our minds are directed to repeat a narrow range of expressions, mostly related to survival. It’s as if we’ve been programmed — like robots — to process war-related terms, while the vocabulary of life has been locked away.

I no longer ask my friends:

“What are your plans for the future?”

“Where do you want to travel?”

“What are your dreams?”

I graduated in 2022. Back then, the future filled every corner of my mind: mastering languages, finding work, building a life.

Now, all of us count sacks of flour and whisper about medicine.

This is more than a change in diction; it is a psychological occupation.

Despite all this, Gaza still resists.

And yet, beneath the rubble and the scent of death, sentences still form.

Gaza cannot be deceived.

Gaza is educated, stubborn, and alive.

We still hold on to hope, even when it thins into the air like smoke.

We did not choose this.

We simply want to live.

To report.

To remember — and, at times, to forget.

But never to forgive.

Lubna Ahmad Abu Dahrouj is a student of the late Dr. Refaat Alareer. She says, “I believe in the power of writing, and I find solace in it during this genocide. Writing serves as both a testimony and a powerful form of resistance. I write for the sake of my people—the people of Gaza. I love my people deeply, and so it is my duty to write.”

Even words have been ridden rough by the entity. This piece is a whole other angle on the cruelty inflicted – and the courage and intelligence of those resisting genocide.