His boys, excited about their first successful hunt, knew they shouldn’t make a sound. Slowly and quietly, they dragged their wet boots over the narrow, cracked concrete ground and walked by the remains of the collapsed wall, listening to the sound of their own shallow breaths and the wild, loud screams of the birds. The heavy, crooked load of their backpacks hunched their backs. They walked carefully, hoping to deliver their fragile cargo to the camp in one piece. The man stopped to take a breath.

He turned his head towards the sun setting behind the scarlet rocky hills that spread across the horizon. A shallow black sea stretched before him, from the cement by-way to the rocks, disrupted by the ghostlike magnitude of the giant birds roaming in the waters and flying in the sky. When he was the same age as his sons, he thought that the birds would seem smaller as he grew up. But the birds, the only other creatures who inherited the drowned earth alongside men, had rapidly grown in size, getting bigger every season.

He went ahead to open the camp fence for his sons. He knew that their hands were sore from the freezing moisture. The worn-out and threadbare clothes passed down to them from previous generations were no match for the cold moisture of the sunset that crept into their skins and made them shiver. He, too, like his sons, was weary of the day’s journey and all he wanted was to rest his tired and shaking legs on dry, warm land. They had set out early in the morning, walked along the concrete path, crossed the black sea, climbed the rocks, and waited for a bird to leave its nest so they could grab the eggs and head back. They were always careful, hiding and escaping from the wild, enormous birds.

The boys followed him down the broken concrete stairs, covered at every turn with layers of metal nets used as fences. The nets separated their hiding place from the never-ending sky-the realm of the birds. As they reached the lower stairs, the campers, scarce in number, came to welcome them back. His wife proudly hugged her sons and the boys gloriously took out the giant and intact eggs from their backpacks and placed them on the feathered racks.

The campfire was running. Unlike the birds, which had snowballed in number, the campers’ population had decreased over the years. Everyone was busy doing something. A group of three young men who had gone out that day to gather firewood unloaded the logs in the designated dry place. Two campers joined to help them segregate the logs by size and place the moist woods in the open air so they would dry up for the next day’s fire.

An older woman sat by the fire on a wooden stool, drawing out thread from worn-out fabrics to use for sewing the old pieces of cloth and making a quilt. Two young women sat beside her on the floor, sorting the feathers by size. Small feathers were piling up to fill the new quilts and large ones were tied together to make waterproof linings to cover the floors, the walls, and the fence in the rain season. The freezing moisture of the rain season took the lives of many campers each year, mostly the children and the old; all they had to fight the cold, humid weather were the enormous wings they gathered from the forest floors every week.

The man gazed at the piles of different-sized feathers and turned his head towards the firewood. They only had three weeks before the rains started and neither the firewood nor the feathers seemed sufficient to last the rain season. He had checked the stored dried insects the day before, and he was confident they could survive the whole rainy season, eating the stored insects. But they had to gather as much feather and firewood anyway and they could go for a few more rounds of egg hunting.

He walked towards the fire. The young bride of the camp was nursing her baby by the fire. They hadn’t named the baby yet. They would wait until after the rainy season and if the baby survived the cold, wet weather, they would give him a name. The man thought of the two babies that he and his wife had lost to the rain season. He remembered the horror, the pain, and the devastation when the fevers started. But there was nothing he could do. Still, he was lucky to have two more sons, surviving and growing up. He tried not to think of what the young bride was going through, her worries and hopes and her never-ending fear of losing a child. She must have heard the bitter and horrifying stories of babies getting sick, and must have been warned constantly of the danger lurking in every corner. The man shut his eyes, pressing his eyelids tightly, and wished in his heart to see that baby grow up, the only baby born to the campers that year.

He took off the wet cloths he used to cover his head and hung them on a rope by the fire. He stood there a little longer, allowing the warmth of the flames to pass through his half-grey beard and reach his face. His oldest son was bragging about the day’s journey to the younger children of the camp, adding daring scenes and excitement to his first hunt story. The man dragged himself to the corner of the egg storage area, sat down and leaned his back against the coarse cement wall. His youngest son sat beside him and soon fell asleep on his arm. He caressed his son and let him rest.

The man remembered his own first hunts and how he became exhausted after a day’s trip. At the time, they didn’t just hunt eggs; they would chase the chicks with spears and nets. Nowadays, the bird chicks were bigger and stronger than the full-grown birds of their childhood. If they had given up hunting the chicks ten years ago and settled for eggs sooner, they wouldn’t have lost so many lives on hunting trips. He shuddered, trying to shake off the memories appearing before his mind: the last image of his father’s body, torn apart by a bird’s bloody beak… He didn’t want to return to the memory of that bitter dusk where he lost his father to a wild bird and returned to the camp empty-handed and alone.

His old mother came to fetch the eggs for dinner.

“Which bird’s egg is this?” She asked curiously.

“I couldn’t tell… the nest was empty. We didn’t see the mother bird. Does it matter?” He replied, annoyed. His mother always asked this question, as if in her realm of knowledge and logic, she still wanted to cage the identity of the birds that had evolved beyond human understanding.

The man carefully laid his son on the floor, trying not to wake him up. He stood up and went to help his mother. She seemed puzzled. He kissed his mother’s grey hair, but his mother looked at the egg, frowning.

She scanned the egg’s shell with her coarse palm and asked again: “This one has a different color shell… slightly different… and a wired shape! What bird did you say you fetched it from?”

Before he was able to answer, the egg started to hatch. The small cracks spread throughout the cluster and the egg cap broke with the pressure of the chick’s head trying to get out. The man excitedly gazed at his mother and the egg. A newly born chick could make an easy hunt and a delicious meal for the campers. But his mother stepped back in horror. The man looked again at the egg and the creature trying to escape it. He quickly turned around, looking for a sharp object, anything that could kill the newly born creature before it left the egg. The world with giant birds was dangerous enough for them. These new creatures, if they survived, would kill both the humans and the birds and no number of fences and nets couldn’t keep them away.

The newborn that had no legs or hands finally slid out from the egg hole and quickly slithered away from the egg, crawling and pouncing forward. The man finally grabbed an iron bar and swung it over the creature, trying to crush its head and long hissing tongue.

But it was too late.

The newborn had already jumped on the leg of his son as he calmly slept on the floor.

Notes:

“The Hatching” was originally published in Farsi in Time Rider, A Collection of Speculative Short Stories by Zoha Kazemi, Tandis Books, Iran.

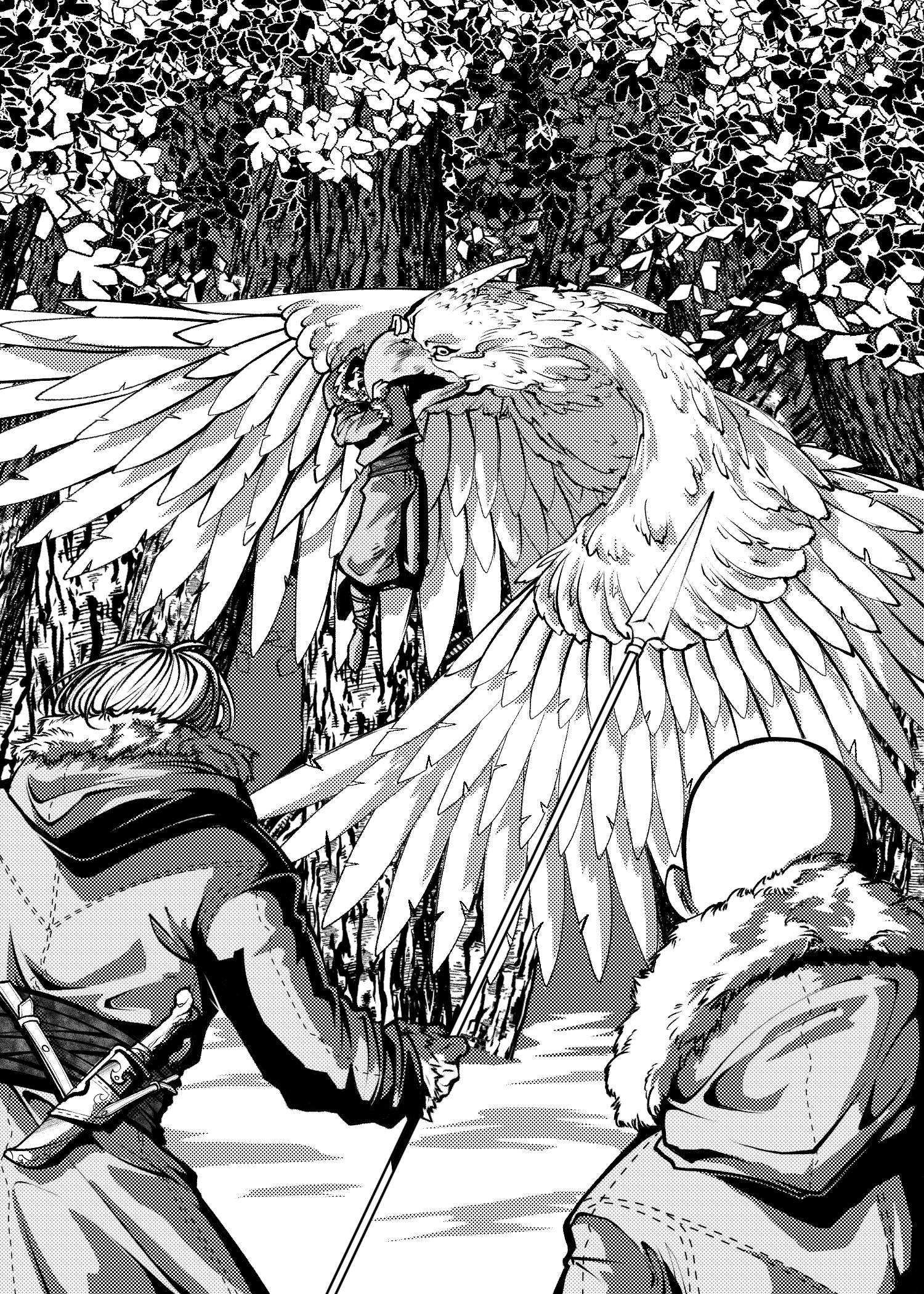

“The Hatching” illustration is by Mahour Pourghadim.