In my work as a professor of creative writing and literature, I am always looking for artfully written books to share with my students. I am intrigued by Mohammed Said Hjiouij’s 2019 novel, Kafka in Tangier (Kafka fi Tanja in phonetic Arabic) because of the characters, narrative style, and literary references. I am equally intrigued by his decision to serialize the novel on substack, which drew a wide audience and resulted in a good amount of discussion on social media. In a December 2021 article on Arablit.org, translator Phoebe Carter explained that the idea to serialize was Mr. Hjiouij’s and that she was “excited by the idea of experimenting with the way translation and publishing is carried out.” I am also excited by this step forward in methods for authors to engage readers. Serializing a compelling piece of literature invites readers into a social experience where conversations and enjoyment of the story become one.

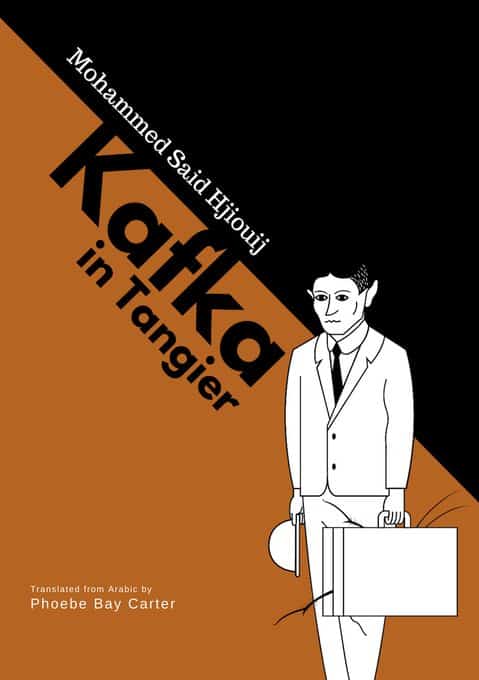

Kafka in Tangier (KafkaInTangier.com) is a retelling of Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, a story whose protagonist transforms into a repulsive thing. Hjiouji’s retelling infuses the original story’s framework with socially relevant details of Moroccan society. The result is a novel that at times is both humorous and troubling while being subtly relatable to many readers because of Hjiouij’s deft portrayal of aspects of universal human experience.

I was curious to learn more about Hjiouij’s specific literary choices so that I could better inform my classroom discussions. Recently, I contacted Mr. Hjiouij and he generously agreed to this interview about his inspiration for writing Kafka in Tangier and his creative approach to developing the novel.

LG: Inspiration and Adaptation: What inspired you to reinterpret Franz Kafka’s “Metamorphosis” in a Moroccan setting, and how did you approach integrating elements of Moroccan culture and history into this classic story?

MSH: I don’t exactly remember how I came up with the idea of writing “Kafka in Tangier,” unlike my other novels. Knowing that memory can be unreliable and prone to narrative fallacy, I cannot claim that the idea struck me like a bolt of lightning. Rather, it might offend some to admit that I was motivated to write the novel because I did not like Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis.” After hearing so much praise for it, I finally read it and found it unimpressive. I thought to myself, What’s so special about this story that everyone admires? I believed that I could write something better than that, and so I began writing my own novel. Only later did I discover that I read a poor Arabic translation of Kafka’s work, and after I had published my book, I read a better Arabic translation directly from German.

Despite admitting that my impulse to write this novel was born out of a desire to write a better book than “The Metamorphosis,” I cannot explain how the details of the story, such as the Moroccan setting and the characters, came to be. While I believe that my subsequent novels are far better than this first one in many ways, I still find myself, somewhat in admiration, astonished by my debut for how it came to me effortlessly and flowed from my subconscious mind to the page. However, this, too, may be a narrative fallacy.

LG: Character Development: The protagonist, Jawad Al-Idrisi, is a complex character with shattered dreams of becoming a literary critic. What challenges did you face in developing his character, especially after his transformation into a monster?

MSH: Indeed, the character of Jawad is intricate, so much so that it still haunts me to this day. It asserted itself in greater detail in my novel “By Night in Tangier” and then in my novel “Labyrinth of Illusions.”

However, in my debut “Kafka in Tangier,” it’s not necessary for the reader to agree with me on this, Jawad’s character is not the primary focus. Instead, he serves as a plot device, and he is not an independent character. Or perhaps this is the true essence of the novel: The novel is about the powerless hero (The anti-hero), the crushed one with no hope of achieving his own dreams, just like Kafka’s protagonists.

Overall, in the novel, we have the character of the father, who has a significant space to reveal his story, contradictions, and the transformation he underwent. Also, we have the sister, to whom the narrator granted the authority to tell her story in her own voice through her diaries. Who is the real protagonist in the novel, truly? Is it the father, or is it Hind, the sister? Perhaps they are intertwined, or perhaps it’s the city itself, the city of Tangier. Yes, it’s a novel about transformations—the transformation that affected the city of Tangier and the transformation that affected the Moroccan family. Thus, to me, the transformation that occurred to Jawad was the spark that made the other transformations prominent, and that’s the essence of the novel.

I did not focus much on developing Jawad’s character post-transformation because I wanted to highlight the other transformations that affected the family members

LG: Themes and Motifs: “Kafka in Tangier” explores themes of transformation, alienation, and power. How do these themes reflect the contemporary societal and cultural issues in Morocco?

MSH: The Al-Idrisi family, in essence, represents a microcosm of Moroccan society. “Kafka in Tangier” is indeed a novel about the transformations that affected both the city and the community. Tangier transformed into a big industrial city, changes that completely altered its face and its population structure.

Similarly, globalization caused a complete transformation of Moroccan society. It shifted from a conservative, closed-off society (at least, that’s how the cities in northern Morocco were) to a completely open one, not much different from European or American societies. Although Islam remained present in the consciousness of the people, there was a decline in ethical values.

This is what I attempted to express (or uncover) in the novel by comparing the status of women from previous generations, represented by Jawad’s mother, to the current generation, represented by Hind, his sister. It shows the family disintegration in contrast to Jawad’s sacrifices for his family and the focus of his sister on her own personal means, as well as the adultery that Jawad experienced on the other hand.

LG: Narrative Structure and Style: Your novel employs a unique narrative structure with multiple perspectives and a blend of magical realism, absurdity, and postmodernism. How did you decide on this structure, and what impact do you think it has on the storytelling?

MSH: As I always say, the form of a novel, the structure and style, is inseparable from its content, from its story. If I were to sit down now and rewrite “Kafka in Tangier” from scratch, I believe I wouldn’t deviate much from the artistic form and structural framework in which I initially wrote the novel. What I mean to say is that during the planning process of the novel, both the thematic elements and the structure are considered together until the novel’s theme matures well in my mind. At that point, the style of writing and planning the novel naturally accompanies the story and the plot.

Literary text, for me, is the fusion of form and content. The form’s significance is what gives the novel its strength and the writer’s unique style. In my three novels, after “Kafka in Tangier,” the reader will find a deeper dive into experimental styles and postmodern formats. I cannot truly answer how I decided to construct each one of them in the manner I did because each one imposed its thematic expression’s form.

For instance, in “By Night in Tangier,” there’s an emotionally unstable character, somewhat suffering from schizophrenia and another organic illness, with limited time left in life. What’s the most appropriate way to express that? Embracing a stream of consciousness without a censor, delving into the protagonist’s mind with all its contradictions and delusions without the intervention of an external narrator.

In my second novel, “The Riddle Of Edmond Amran El Maleh,” the protagonist is haunted by a past he’s not entirely content with. How can the novel reveal this? With a complete loss of memory, the protagonist finds himself in a closed room, driven by the desire to dig into his memory to write down everything he remembers. The pen races between his fingers rapidly before all memories vanish, resulting in a narrative flowing incessantly without order, and he doesn’t even know if he’s a real person or a character in someone else’s novel. Yet, prior to that, in the initial experiment of writing this novel, the narrator was death. However, the novel didn’t surround itself to that “form.” It resisted flowing and defied until many waters ran under the bridge of writing, and the idea transformed multiple times before finally surrounding itself in the form it was released in. Although I “wanted” to write a novel narrated by death, I resisted succumbing to that wish and forcing the text into a cesarean birth, allowing it to come out as I wanted, exerting control over it arbitrarily. Ultimately, after multiple experiments, the most suitable form came with surrendering the novel to the voice of Edmond Amran, trapped in a limbo, and then the narrative flowed smoothly.

As for “Labyrinth of Illusions,” it’s about the writer, a novelist, and the worlds spinning in his head. Therefore, the most suitable format was to write the novel in the form of three books, presenting three apparently separate narratives that represent a musical counterpoint revealing to a large extent what’s going on in the writer’s mind—interlocking and conflicting thoughts.

And so, with each novel, the appropriate artistic form emerges. If it doesn’t, I don’t go beyond the first chapter, continuing to rewrite it until the form harmonizes with the content. At that point, the idea of the novel has matured, and the writing continues smoothly.

LG: Family Dynamics and Social Commentary: The relationships within Jawad’s family, especially between him and his father Mohammed, are central to the narrative. Could you elaborate on the significance of these family dynamics and how they contribute to the broader social commentary of the novel?

MSH: Perhaps the situation has begun to change in recent years, but during the years in which Jawad grew up, Moroccan families, in general, were subject to absolute dominance by the father. The father was the sole authority figure, and no one could challenge him or even make suggestions. This was a common custom in many societies, including Europe in the past, and even Kafka suffered from the dominance and persecution of his father.

In the story, the father is the kind who doesn’t work, sits at home, and forces his children to work while providing for the household. This applies not only to the boys but also to the girls, as seen with Jawad’s sister Hind, who was pushed by her father to work as a waitress in a café. Though girls engaging in this kind of work have become more common in recent years, it was considered questionable and subjected them to suspicion just a decade ago.

The novel touches on many other themes, such as adultery, the beliefs of mothers in superstitions and magic, and the oppression of authority over citizens.

LG: Literary Influences and References: “Kafka in Tangier” is rich in literary references and plays with different narrative forms. Could you discuss some of the literary works or authors that influenced your writing of this novel?

MSH: I guess that my adoption of a thin layer of magical realism was directly influenced by Salman Rushdie, and I don’t think I can pinpoint all the writers who directly influenced the writing of “Kafka in Tangier” by myself. Perhaps critics can do that better than me. What I can say, in general, is that elements of influence from various writers can be found in my novels: Paul Auster, Salman Rushdie, Umberto Eco, Roberto Bolaño, to some extent Milan Kundera, as well as Haruki Murakami.

LG: Response to Adaptation: How do you feel about the response from readers and critics to your adaptation of Kafka’s work? Were there any reactions that particularly surprised or intrigued you?

MSH: According to Goodreads and NetGalley, it appears that Western readers have a more favorable opinion of the novel compared to Arab readers who are somewhat undecided between liking and disliking it. However, it is important to note that the Arabic reading market is quite limited, and the novel was originally published poorly in Arabic, which may have influenced the reader’s perception.

Overall, I am pleased with the novel’s reception, which turned out to be better than expected. I was recently amazed and gratified to read a paper presented by a Syrian critic at an academic seminar. Furthermore, the first chapter of the novel has been translated into Hebrew and Italian. The novel has also gained the trust of a Greek publisher and is expected to be released in Greece next month.

LG: Which languages has your book been translated into and who is the audience those translators and publishers hope to reach?

MSH: Before the English translation, a Kurdish publisher in Denmark decided to publish the Kurmanji translation. Although the translation was ready months ago, the publication date is yet to be determined. The Greek translation may be released next month or even before. The first chapter of Kafka in Tangier has been translated into Hebrew, and a publisher has shown interest, but the situation in the region is not conducive to such luxuries. The Spanish translation is expected to be released in February.

As for the target audience, I don’t have much information. However, I assume that the publisher is targeting readers who are interested in literature translated into their local language and are curious about Arab culture. Additionally, the academic audience, including Arabic language scholars and critics, is always a target.

LG: Future Projects: Following “Kafka in Tangier,” do you have any upcoming projects or novels that you are currently working on or planning?

MSH: I have published three novels in Arabic after “Kafka in Tangier”. The fourth one is ready and I have already signed a contract with the publisher. However, I am not very excited about publishing it. I had asked for a few months’ delay in its publication earlier and I might request another delay. The state of readership in the Arab world is not very encouraging and it is quite disheartening.

I used to love writing the novel, but now I am not sure. I don’t know why I write and for whom, especially when the readership is small and is influenced by the power of a few publishers and the award lists. This situation is quite disheartening.

أثناء عملي كأستاذة للأدب والكتابة الإبداعية، أبحث دومًا عن الكتابة المكتوبة بحرفة لأشاركها مع تلاميذي. لقد أثار اهتمامي رواية “كافكا في طنجة” تأليف محمد سعيد احجيوج الصادرة عام 2019، بسبب شخصياتها، وأسلوب كتابتها، ومراجعها الأدبية. كما أثار اهتمامي أيضًا نشر الرواية في حلقات متسلسلة على موقع substack لجذب جمهور أوسع، مما أدى لإثارة نقاش حول الرواية على مواقع التواصل الاجتماعي. في مقال نُشر في ديسمبر 2021 على موقع Arablit.org أوضحت المترجمة فيبي كارتر أن نشر الرواية في حلقات كان فكرة السيد احجيوج وأنها كانت “متحمسة لفكرة تجربة هذه الطريقة في الترجمة والنشر”. وأنا متحمسة أيضًا لهذا الأسلوب الجديد في التفاعل ما بين المؤلف وجمهوره. إن نشر عمل أدبي متقن في حلقات متسلسلة من شأنه أن يؤدي إلى تجربة اجتماعية جديدة تجمع ما بين الاستمتاع بالقصة ومناقشتها.

كافكا في طنجة هي إعادة لسرد رواية “التحول” تأليف فرانتس كافكا، القصة التي يتحول بطلها إلى شيء مثير للاشمئزاز. إن رواية احجيوج تضفي على إطار القصة الأصلية تفاصيل اجتماعية متعلقة بالمجتمع المغربي. والنتيجة هي رواية تكون في بعض الأحيان مرحة، وفي أحيان أخرى مثيرة للاضطراب، ويشعر العديد من القراء بشكل غير مباشر بالارتباط بينهم وبين الرواية بسبب تصوير احجيوج البارع للتجربة الإنسانية العالمية.

كنت مهتمة بمعرفة المزيد عن اختيارات احجيوج الأدبية المميزة لكي أثري مناقشات طلابي بشكل أفضل. تواصلت مؤخرًا مع السيد احجيوج وقد تكرم بالموافقة على إجراء هذا الحوار بشأن مصادر الإلهام وراء كتابته لرواية كافكا في طنجة، ومنهجه الإبداعي في كتابة الرواية.

LG

الإلهام والاقتباس: ما الذي ألهمك لإعادة صياغة رواية فرانتس كافكا “التحول” في بيئة مغربية، وكيف تعاملت مع دمج العناصر الثقافية والتاريخية المغربية مع هذه القصة الكلاسيكية؟

MSH

عكسَ رواياتِي الأخرياتِ، لا أتذكّرُ بالضبطِ كيفَ قررتُ الانطلاقَ في كتابةِ “كافكا في طنجة”.

لولا أنَّني أعرفُ أنَّ الذاكرةَ هشةٌ لا يمكنُ الوثوقُ بها، وأعرفُ إغراءاتِ المغالطاتِ السرديةِ وكيفَ يحبُّ الكتّابُ اختراعَ قصصٍ خياليةٍ لبداياتِهمْ، لولا ذلكَ، لقلتُ إنَّ الأمرَ جاءَ على شكلِ إلهامٍ سماويٍّ. هكذا، بينَ لحظةٍ وأخرى: انبثقتْ في عقلِي فكرةُ الروايةِ.

لكنَّ هذا مجانبٌ للصوابِ.

ربما الحقيقةُ التي قدْ تبدو للبعضِ مستهجنةً هيَ أنَّني قررتُ كتابةَ روايتِي لأنَّ روايةَ كافكا لمْ تعجبْني؛ فبعدَ سنواتٍ منْ سماعِ المديحِ المُتكرِرِ لروايةِ كافكا، قرأتُ أخيراً “التحولَ” ولمْ تعجبْني. فكّرتُ آنذاكَ: ما المميزُ في هذهِ القصةِ التي أعجبتِ العالمَ كلَّهُ؟ يمكنُني أنْ أكتبَ أفضلَ منها. وهكذا انطلقتُ في كتابةِ روايتِي. إنَّما علمتُ لاحقًا أنَّ حظي أوقعَني في ترجمةٍ عربيةٍ سيئةٍ لروايةِ كافكا، وقرأتُ لاحقًا، بعدَ أنْ نشرتُ روايتي، ترجمةً عربيةً أفضلَ لروايةِ كافكا، مباشرةً منْ الألمانيةِ.

معَ ذلكَ، رغمَ هذا الإقرارِ بأنَ دافعَ كتابتِي لـ “كافكا في طنجة” هوَ نوعٌ من التحدي لكتابةِ روايةٍ أفضلَ من التحولِ، إلا أنَّني لا أملكُ أيَّ تفسيرٍ لكيفَ ولدت التفاصيلُ اللاحقةُ في الروايةِ، مثلَ البيئةِ المغربيةِ وتركيبِ الشخصياتِ. الحقيقةُ هيَ: رغمَ أنَّ رواياتِي الأخرياتِ أفضلُ منْ روايتِي الأولى، منْ نواحِي كثيرةٍ، إلا أنَّني أجدُني أقفُ، بشيءٍ منْ الإعجابِ، مندهشًا أمامَ روايتِي الأولى، القصيرةِ جدًا والمتواضعةِ، كيفَ أنَّها كتبتْ نفسَها، وتدفقتْ منْ عقلِي الباطنِ إلى القلمِ. حسنًا، أعترفُ: هذهِ أيضًا مغالطةٌ سرديةٌ.

LG

كتابة الشخصية: البطل جواد إدريس شخصية معقدة بأحلام محطمة لأن يصير ناقدًا أدبيًّا. ما التحديات التي واجهتها في كتابة شخصيته، وخصوصًا بعد تحوله إلى وحش؟

MSH

فعلاً، شخصيةُ جوادٍ مركبةٌ، وبالغةُ التعقيدِ، إلى درجةِ أنَّها ما زالتْ تلاحقُني حتى الآنَ، وفرضتْ نفسَها بتفصيلٍ أكبرَ في روايتِي “ليلُ طنجةَ”، ثمَّ في روايتي “متاهةُ الأوهامِ”.

في روايةِ “كافكا في طنجةَ” لمْ أركزْ حقيقةً على جوادٍ. بالنسبةِ إليَّ، وهذا أمرٌ ليسَ ضرورياً أنْ يتفقَ معي القارئُ بخصوصِهِ؛ شخصيةُ جوادٍ ليستْ هيَ الشخصيةُ الأساسيةُ في الروايةِ، بلْ هيَ أداةٌ لتحريكِ الحبكةِ أكثرَ مما هيَ شخصيةٌ مستقلةٌ. أوْ ربما هذا هوَ جوهرُ الروايةِ الحقيقيّ: إنّها عنْ البطلِ مسلوبِ القوةِ، المطحونِ الذي لا أملَ لهُ في تحقيقِ أحلامِهِ الخاصةِ. تمامًا مثلَ أبطالِ كافكا.

عمومًا، لديْنا في الروايةِ شخصيةُ الأبِ التي حصلتْ على حيزٍ كبيرٍ لإظهارِ حكايتِها، وتناقضاتِها، والتحولِ الذي طرأَ عليها. أيضاً لديْنا الأختُ، التي منحَها الراوي صلاحيةَ أنْ تحكيَ قصتَها بصوتِها هيَ، منْ خلالِ يومياتِها. منْ هوَ البطلُ، حقًا، في الروايةِ؟ هلْ هوَ الأبُ أمْ هيَ الأختُ هندٌ؟ ربما هما معًا، أوْ ربما هيَ المدينةُ نفسُها؛ مدينةُ طنجةَ. نعمْ، هيَ روايةٌ عنْ التحولاتِ، التحولُ الذي طالَ مدينةَ طنجةَ، والتحولُ الذي طالَ الأسرةَ المغربيةَ. لذلكَ، بالنسبةِ إليَّ، التحولُ الذي ظهرَ على جوادٍ كانَ الشرارةَ التي جعلتْ التحولاتِ الأخرى بارزةً، وهذهِ هيَ الروايةُ.

لمْ أشغلْ نفسِي كثيرًا بتطويرِ شخصيةِ جوادِ ما بعدَ التحولِ، لأنَّني ركزتُ على إبرازِ التحولاتِ الأخرى التي طالتْ أفرادَ الأسرةِ.

LG

التيمة والموتيف: تستكشف “كافكا في طنجة” تيمات التحول والاغتراب والسلطة. كيف تعكس هذه التيمات القضايا الاجتماعية والثقافية المعاصرة في المغرب؟

MSH

تمثلُ أسرةُ جوادٍ الإدريسيِّ نسخةً مصغرةً من المجتمعِ المغربيِّ. “كافكا في طنجةَ” هيَ فعلاً روايةٌ عن التحولاتِ التي طالت المدينةَ والمجتمعَ. تحولتْ طنجةُ إلى مدينةٍ صناعيةٍ كبيرةٍ؛ تحولاتٌ غيرتْ وجهَ المدينةِ تمامًا، وتركيبتَها السكانية.

كذلكَ، وبالنظرِ إلى انفتاحِ الحدودِ أمامَ هيمنةِ العولمةِ، تغيّرَ المجتمعُ تمامًا، دفعةً واحدةً، منْ مجتمعٍ محافظٍ منغلقٍ على نفسِهِ (على الأقلِّ هكذا كانت مدنُ شمالِ المغربِ) إلى مجتمعٍ منفتحٍ كلّيًا، لا يختلفُ عنْ المجتمعِ الأوروبيِّ أوْ الأمريكيِّ، حتى وإنْ بقيَ الانتماءُ الدينيُّ إلى الإسلامِ حاضرًا في الوعيِ، إلا أنَّ الانفتاحَ الأخلاقيَّ، أوْ إذا أردت التعبيرَ بحكمٍ قيميٍّ؛ الانحلالُ الأخلاقيُّ، فرضَ نفسَهُ.

هذا ما حاولتُ التعبيرَ (أو الكشف) عنهُ في الروايةِ، منْ خلالِ المقارنةِ بينَ وضعِ المرأةِ منْ الأجيالِ السابقةِ ممثلةً في أمِّ جوادٍ، والمرأةُ في العصرِ الحاليِّ ممثلةٌ في الأختِ هندٍ. إظهارُ التفسخِ العائليِّ بالمقارنةِ معَ تضحياتِ جوادٍ لأجلِ عائلتِهِ وبينَ تركيز الأختِ على أحلامِها الشخصيةِ، وكذلكَ الخيانةُ الزوجيةِ منْ جهةٍ أخرى التي تعرض لها جواد.

LG

البنية والأسلوب السردي: توظف روايتك بنية سردية ذات وجهات نظر متعددة وتمزج ما بين الواقعية السحرية والعبثية وما بعد الحداثة. كيف قررت اختيار هذه البنية، وما تأثيره على السرد القصصي من وجهة نظرك؟

MSH

كما أقولُ دائمًا، شكلُ الروايةِ لا ينفصلُ عنْ مضمونِها. إذا أردتُ أنْ أجلسَ الآنَ، وأعيدُ كتابةَ “كافكا في طنجةَ”، منْ الصفرِ، أعتقدُ أنَّني لنْ أبتعدَ كثيرًا عنْ الشكلِ الفنيِّ والبناءِ الهيكليِّ الذي كتبتُ بهِ الروايةَ أولَ مرةٍ. ما أريدُ قولَهُ: إنَّه خلالَ عمليةِ التخطيطِ للروايةِ، فإنَّ التفكيرَ والتخطيطَ يشملانِ الشكلَ كما الموضوعِ، معًا، إلى أنْ يختمرَ موضوعُ الروايةِ جيدًا في ذهنِي، آنذاكَ فإنَّ طريقةَ كتابتِهِ وتخطيطَ الروايةِ تأتيانِ تلقائيًا معَ الموضوعِ.

النصُّ الأدبيُّ عندِي هوَ تمازجُ الشكلِ والمضمونِ. أهميةُ الشكلِ التعبيريِّ هيَ ما يمنحُ الروايةَ قوّتَها والكاتبَ بصمتَهُ. في رواياتِي الثلاثِ، بعدَ “كافكا في طنجةَ”، سيجدُ القارئُ غوصًا أكبرَ في الأساليبِ التجريبيةِ، وصيغَ ما بعدَ الحداثةِ. لا يمكنُني حقًا أنْ أجيبَ عنْ سؤالِ كيفَ قررتُ بناءَ كلِّ واحدةٍ منها، بالشكلِ الذي كتبتُها بهِ، لأنَّهُ وببساطةِ كلُّ واحدةٍ منها فرضَ موضوعُها شكلَ التعبيرِ عنهُ. مثلاً، لديْنا في “ليلِ طنجةَ” شخصٌ غيرُ مستقرٍّ نفسيًا، يعاني الفصامَ إلى حدٍّ ما، معَ مرضٍ عضويٍّ آخرَ، وأيامه المتبقيةِ في الحياةِ معدودةٌ. ما هيَ أنسبُ طريقةٍ للتعبيرِ عنْ ذلكَ؟ اعتمادُ تيارِ الوعيِ المتدفقِ دونَ رقيبٍ، حتى نطّلعَ على ما يدورُ في عقلِ البطلِ، بكلِّ تناقضاتِهِ وأوهامِهِ، دونَ وساطةٍ منْ راو خارجيٍّ.

لديْنا في روايتي الثانيةِ “أحجيةُ إدمون عمرانَ المالحِ” بطلٌ يلاحقُهُ ماضٍ ليسَ راضيًا عنهُ تمامًا. كيفَ يمكنُ للروايةِ أنْ تكشفَ عنْ ذلكَ؟ فقدانٌ تامٌّ للذاكرةِ، والبطلُ يجدُ نفسَهُ في غرفةٍ مغلقةٍ مسكونٌ برغبةِ أنْ يحفرَ في ذاكرتِهِ ليكتبَ كلَّ ما يتذكرُهُ. يجري القلم بين أصابعهِ بسرعةٍ قبلَ أنْ تختفيَ كلُّ الذكرياتِ، فيأتي سردُهُ متدفقًا دونَ توقفٍ ودون ترتيب، وهوَ لا يعرفُ حتى إذا ما كانَ شخصا حقيقيًا أمْ هوَ شخصيةٌ في روايةٍ يكتبُها كاتبٌ آخرُ. لكنْ قبلَ ذلكَ، في التجربةِ الأولى لكتابةِ الروايةِ، كانَ الراوي هوَ الموتُ. لكنَّ الروايةَ لمْ تسلمْ نفسَها وفقَ ذلكَ “الشكلِ”. بقيتْ تقاومُ المخاضَ، وتعاندُ حتى جرتْ مياهٌ كثيرةٌ تحتَ جسرِ الكتابةِ، وتحولت الفكرةُ أكثرَ منْ مرةٍ قبلَ أنْ تسلمَ نفسَها بالشكلِ الذي صدرتْ بهِ. رغمَ أنَّني كنتُ “أريدُ” أنْ أكتبَ روايةً يرويها الموتُ، إلا أنَّني قاومتُ الرضوخَ لتلكَ الأمنيةِ وإكراهَ النصِّ على الولادةِ القيصريةِ ليخرجَ كما أريدُهُ أنا متسلطًا عليهِ بتعسفٍ. في نهاية الأمر، وبعدَ تجاربَ متعددةٍ، جاءَ الشكلُ الأنسبُ بتسليمِ الروايةِ لصوتِ إدمونِ عمرانِ المالحِ العالقِ في مكانٍ/زمانٍ برزخيٍّ، عندها تدفقتِ الروايةُ بسلاسةٍ.

أما “متاهةُ الأوهامِ” فهيَّ عن الكاتبِ، كاتبٌ روائيٌّ، عنْ العوالمِ التي تدورُ في رأسهِ، ومن ثم كانتِ الصيغةُ الأنسبُ هيَ كتابةُ الروايةِ على شكلِ ثلاثة كتبٍ، تقدمُ ثلاثَ حكاياتٍ منفصلةٍ ظاهريا، لكنَّها تمثّلُ طباقًا موسيقيًا يكشفُ إلى حدٍّ كبيرٍ عما يدورُ في رأسِ الكاتبِ من أفكار متداخلةٍ ومتصادمةٍ.

وهكذا، معَ كلِّ روايةٍ يأتي الشكلُ الفنيُّ المناسبُ لها. أما إذا لمْ يأتِ، فإنَّني لا أتجاوزُ الفصلَ الأولَ، وأستمرُّ في إعادةِ كتابتِهِ حتى يتجانسَ الشكلُ معَ المضمونِ، عندها تكونُ فكرةُ الروايةِ قدْ اختمرتْ وتتواصلُ الكتابةُ بسلاسةٍ.

LG

الديناميكية العائلية ونقد المجتمع: العلاقات داخل عائلة جواد ـ وخصوصًا ما بينه وبين والده محمد ـ تمثل محور السرد. هل يمكنك أن توضح أهمية هذه الديناميكية العائلية، وكيف تساهم في النقد الاجتماعي الموسع الذي تطرحه الرواية؟

MSH

ربما الوضعُ بدأَ يتغيّرُ خلالَ السنواتِ الأخيرةِ، لكّن خلالَ السنواتِ التي نشأَ فيها جوادٌ كانتِ الأسرةُ المغربيةُ، في العمومِ، خاضعةً لهيمنةٍ مطلقةٍ للأبِ. الأبُ هوَ صاحبُ السلطةِ الوحيدةِ، ولا أحدَ يمكنُهُ الوقوفُ أمامَهُ بأيِّ MSH: اعتراضٍ ولا حتى اقتراحٍ. أعتقدُ أن هذا أمرٌ معتادٌ في أغلبِ المجتمعاتِ، وحتى في أوروبا خلالَ العقودِ الماضيةِ، وكافكا نفسُهُ عانى منْ تسلّطِ الأبِ واضطهادِهِ.

الأبُ في هذهِ الروايةِ يمثلُ أحد نماذجِ الآباءِ الشائعةِ، وهوَ الأبُ الذي يتوقفُ عنْ العملِ، ويجلسُ في البيتِ ملزِمًا أبناءَهُ بالعملِ والنفقةِ على البيتِ، ولا يتوقفُ الأمرُ هنا على الذكورِ، بلْ حتى الفتياتِ، كما نرى معَ الأختِ هندٍ التي دفعَها أبوها للعملِ نادلةً في مقهىً. حاليًا بدأتْ ظاهرةُ اشتغالِ الفتياتِ بهذا النوعِ منْ العملِ في الانتشارِ، لكنْ قبلَ عقدٍ منْ الزمنِ فقطْ كانَ الأمرُ مثيرًا للريبةِ، ويعرضُ الفتاةَ لكثيرٍ منْ سوءِ الظنِّ.

هاذينِ جانبان اثنان منْ الجوانبِ الاجتماعيةِ التي تتطرقُ إليها الروايةُ، والمواضيعُ الأخرى متعددةٌ، مثلَ: الخيانةِ الزوجيةِ، اعتقادِ الأمهاتِ (النساءِ منْ الأجيالِ السابقةِ) في الخرافةِ والسحرِ، اضطهادِ السلطةِ للمواطنِ، إلخْ.

LG

مصادر الإلهام الأدبية والإشارات المرجعية: “كافكا في طنجة” ثرية بالإشارات المرجعية، وتوظف أساليب سردية مختلفة. هل يمكنك أن تذكر بعض الأعمال الأدبية أو المؤلفين الذين تأثرت بهم أثناء كتابة هذه الرواية؟

MSH

أعتقدُ أنَّ اعتمادِي لطبقةٍ خفيفةٍ من الواقعيةِ السحريةِ جاءَ بتأثيرٍ مباشرٍ منْ سلمانَ رشدي، ولا أظنُّني قادرًا على أنْ أحددَ بنفسِي كلَّ الكتّابِ الذينَ أثّروا مباشرةً في كتابةِ “كافكا في طنجةَ”. ربما النقادُ يمكنُهمْ ذلكَ أفضلُ مني. MSH: ما يمكنُني قولُهُ، بشكلٍ عامٍّ، أنّه يمكنُ العثورُ في رواياتِي المختلفةِ على عناصرِ تأثرٍ من: بول أوستر، سلمانَ رشدي، إمبرتو إيكو، روبرتو بولانيو، وإلى حدٍّ ما ميلان كونديرا، وكذلكَ هاروكي موراكامي.

LG

الاستجابة إلى الاقتباس: كيف تشعر حيال استجابة القراء والنقاد لاقتباسك أحد أعمال كافكا؟ هل كان هناك أي ردود فعل فاجأتك أو أثارت اهتمامك بشكل خاص؟

MSH

إذا اعتمدتُ على جودريدز لتلقيَ انطباعاتِ القرّاءِ، فإنَّ تلقيَ القارئِ الغربيِّ للروايةِ جاءَ أكثرَ احتفاليةً بالروايةِ، مقارنةً بالقارئِ العربيِّ الذي بقيَ متذبذبا بينَ الإعجابِ وعدمِ الإعجابِ. الحقيقةُ أنَّ سوقَ القراءةِ بالعربيةِ محدودٌ جدًا، ومنْ جهةٍ أخرى صدرتْ الروايةُ في الأصلِ العربيِّ بشكلٍ سيءٍ جداً (أقصدُ التصميمَ الداخليَّ للكتابِ) وربما يكونُ ذلكَ أثّرَ على القارئ في تلقي الروايةِ.

إجمالاً، أظنُّ أنَّ تلقيَ الروايةِ جاءَ أفضلَ مما توقعتُ. قرأتُ مؤخرًا دراسةً نقديةً شاركت بها ناقدةٌ سوريةٌ في لقاء أكاديمي، وحقيقةً أدهشتْني، وأعجبتْني كثيرًا. كما سبق أن ترجمَ فصلُ الروايةِ الأولِ إلى العبريةِ والإيطاليةِ، وَحصلت الروايةُ مؤخرًا على ثقةِ ناشرٍ يونانيٍّ ويفترضُ أنْ تصدرَ في اليونانِ الشهرَ القادمَ.

LG

ما هي اللغات التي تُرجم إليها كتابك، وما الجمهور الذي يأمل هؤلاء المترجمون والناشرون أن يصل العمل إليه؟

MSH

قبلَ الترجمةِ الإنجليزيةِ قرّرَ ناشرٌ كرديٌّ في الدانمارك نشرَها، ورغمَ أنَّ الترجمةَ جاهزةٌ منذُ شهورٍ، إلا أنَّ موعدَ النشرِ لمْ يتحددْ بعدُ. أما الترجمةُ اليونانيةُ، فربما تصدرُ الشهرَ القادمَ. الفصلُ الأولُ منْ الروايةِ ترجمَ إلى العبريةِ، وهناكَ اهتمامٌ مبدئيٌّ منْ أحدِ الناشرينَ، لكنْ للأسفِ الأوضاعُ في المنطقةِ لا تسمحُ بمثلِ هذا الترفِ. والترجمةُ الإسبانيةُ قادمةٌ خلالَ فبراير.

أما نوعيةُ الجمهورِ الذي يستهدفُهُ الناشرُ فلا أعرفُ عنْ ذلكَ شيئاً. يمكنُني الافتراضُ أنَّهُ جمهورُ القراءِ المهتمِّ بالأدبِ المترجمِ إلى لغتِهِ المحليةِ، ولديْهِ فضولٌ للاطلاعِ على الثقافةِ العربيةِ. وطبعًا يبقى الجمهورُ الأكاديميُّ (دارسي اللغةِ العربيةِ) والنقادُ مستهدفًا دائمًا.

LG

المشاريع المستقبلية: بعد “كافكا في طنجة” هل هناك أي مشاريع مستقبلية أو روايات تعمل عليها الآن أو تخطط لها؟

MSH

بالعربيةِ؛ صدرتْ لي ثلاثُ رواياتٍ بعدَ كافكا في طنجةَ. الرابعةُ جاهزةٌ، وفعلاً تعاقدتُ معَ ناشرِها، معَ ذلكَ لستُ متحمسا لنشرِها، وسبقَ أنْ طلبتُ منْ الناشرِ تأجيلَ نشرِها بضعةَ أشهرٍ، وربما أطلبُ التأجيلَ مرةً أخرى. وضعُ القراءةِ في العالمِ العربيِّ ليسَ مشجعاً. إنَّهُ محبطٌ.

كنتُ أستمتعُ بكتابةِ الروايةِ، أما الآنَ: لا أعرفُ. لمْ أعدْ أعرفُ لماذا أكتبُ ولمنْ أكتبُ، طالما أنَّ جمهورُ القراءِ صغيرٌ، ويبقى خاضعًا لتوجيهاتِ قوائمِ الجوائزِ وهيمنةِ عددٍ محدودٍ منْ الناشرينَ. الوضعُ محبطٌ جدًا.

Notes:

Kafka in Tangier was first published in the original Arabic in 2019 by Dar Tabarak for Publishing and Distribution.

See KafkaInTangier.com for more information.

Mohammed Said Hjiouij: The responses in English were originally composed in Arabic, then translated through ChatGPT, and edited with the assistance of Grammarly.

With appreciation to Ahmed Salah Al-Mahdi for assisting the editor with the translation of the opening paragraphs and interview questions from English to Arabic.