Even twenty-three years after his passing, the shadow of Edward Said—Palestinian by birth, American by experience, and humanist by conviction—still stretches across the global intellectual landscape. Debate surrounds him as passionately today as when he first unsettled the world with Orientalism, that seismic book which cracked open certainties and forced cultures to confront their reflections. To imagine his legacy limited to the Palestinian cause is to misunderstand the breadth of his vision: Said spoke to

humanity at large, to the ways power shapes stories, and to the fragile dignity of those whose voices history tries to silence.

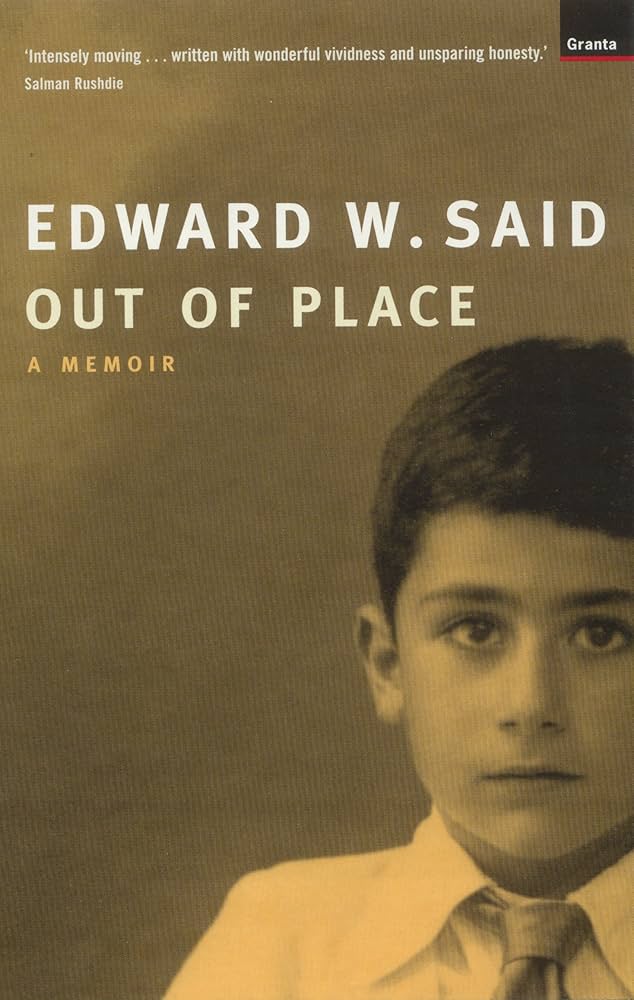

His complex identity—as an Arab-Palestinian Christian born in Jerusalem, raised and educated in Egypt, and later pursuing higher education before becoming a naturalized American citizen—has understandably been seen as a major force shaping his profound reflections on identity, displacement, and exile. It is not merely that he was, as he wrote in Out of Place: A Memoir, tormented by the question of belonging to multiple, and sometimes conflicting, geographies. Beyond this personal dimension, his early academic interests also reveal a professional preoccupation with the instability of identity itself, evident in his seminal work on Joseph Conrad and the fictionality of biography. For Said, the boundaries between life, narrative, and place were never fixed; they were always in motion, mirroring his own unsettled journey across cultures and continents.

In contrast to many others—both intellectuals and laypersons—Said refused to dissolve into the cultural and political norms of the West, although he belonged by way or another to it. Rather, he consciously maintained his position as a distinctly Palestinian voice articulated from within Western institutions. His identity, moreover, became a site of political contestation: it was scrutinized, interpreted, and at times instrumentalized in ways that intersected uneasily with his role as a prominent professor at Columbia

University. The cost of this position was considerable; Said endured threats to his life, a consequence of his steadfast and publicly articulated stance that challenged the dominant pro-Israeli orientations shaping much of the Western political and academic landscape.

Said has always maintained that the diversity of communities’ cultures is an untimely historical process, but by no means a means of subjection and oppression of others under different claims; this is what he forcefully argued in his book Culture and Imperialism. Culture has been viewed from many perspectives. Said’s thesis about how to understand the nature of some conflicts politically or intellectually, either as a pure ideological envisioning or as similar to Huntington’s theory of the Clash of

Civilizations, which Said vehemently rejected.

For Said, the Palestinian issue is not a mere academic debate being widely handled by a minor group of intellectuals; he further engaged politically in practice-informally- as a member of the National Council POL until his resignation in 1991. In this stance, he symbolically used rather than an active politicians do. However, he was present when the Palestinian State was established under the Oslo Accords between the State of Israel and the PLO. He criticized the negotiation process by which a new political turbulence had already erupted in semi-state form, emerging as the Palestine Authority, as a sort of limited democratic existence under Israeli control. Accordingly, he wrote a

book, Peace and Its Discontents, in which he fundamentally analyzes that it would not secure a lasting peace but was a way of political surrender.

What is the Palestinian Narrative?

As a people displaced and uprooted from their homeland, the Palestinians have faced the emergence of a new, eccentric state—one backed on the one hand by theological and historical claims, and on the other by the political support and sustained efforts of Zionism. In this context, the defeated nation—Palestinians and Arabs alike—has not only resisted in order to restore stolen land, but has also struggled to preserve its cultural heritage, which for centuries has embodied its linguistic and cultural identity.

This resistance is fundamentally a defense of an identity that has been historically formed and, despite relentless attempts at physical and spiritual eradication, has proven

its resilience and continued existence. Within this struggle, Edward Said’s perseverance and unique intellectual position enabled him to articulate the Palestinian cause on

numerous international platforms, giving voice to a people systematically silenced and dispossessed.

In essence, the Palestinian narrative is nothing other than the Palestinian cause itself—whether understood as the political and legal right to the land of its indigenous inhabitants, or as the right of a people to exist as a nation with a deep civilizational and historical heritage rooted in its regional sphere. Edward Said successfully interpreted,

through his expansive and unbounded knowledge, how the Palestinian narrative could be articulated and understood within the framework of Western values.

He forcefully interrogated the mechanisms that for a long time had constructed and depicted the “Other” in Western thought, of course including the issue of Palestine—across philosophy, literature, and institutional discourse—where myth and reality were often fused. These mechanisms deliberately produced a vague and obscured image, one that required critical dismantling and careful restatement.

If the Palestinian narrative means anything at all to the world, it is inseparable from the question of identity, which for Edward Said is neither a purely theoretical abstraction

nor merely a matter of legal or constitutional definition through which a state is formally recognized. Rather, Said argues in Culture and Imperialism that Western dominance

and conceptual authority have been shaped far more profoundly by cultural formations and representational practices than by military power alone.

Throughout his defense of Palestinian rights, Edward Said sought to dismantle the dominant stereotypes embedded in Western political and popular imagery that denied

the very existence of the Palestinian people. Amid ongoing turbulence and political upheaval, his mission was far from easy, as it required confronting deeply entrenched

representations that had been constructed and reinforced over centuries. What proved essential, however, was his sustained engagement in rigorous and laborious debate

aimed at challenging, deconstructing, and ultimately revising these distorted and fabricated images.

As a sharp critic of U.S. policy toward the Palestinian issue and its persistent bias in favor of Israel, Edward Said consistently challenged these policies, particularly in the

context of the so-called peace process that culminated in the establishment of the Palestinian Authority. In his seminal work The Question of Palestine, Said demonstrates how American policy has shaped and influenced broader Western governmental approaches to Palestine. Grounded in the strategic alliance between the United States and Israel, these policies, he argues, have had profoundly adverse effects on Western engagement in the region. Said further situates this imbalance within a historical and cultural framework, tracing the underlying cultural narratives that have long informed U.S. relations with Israel and with the Arab world as a whole.

Out of Place in the World

Edward Said’s preoccupation with Palestine—interwoven with his intellectual pursuits, multilingualism, and engagement with everyday life—can be clearly traced in his

memoir Out of Place. The work reflects not only his personal biography but also constitutes a monumental account of his formative years, revealing the emergence of a

thinker who consistently challenged conventional frameworks and thought beyond established boundaries. Within this intellectual trajectory, Said introduced and

rearticulated a range of critical concepts that later became central to postcolonial discourse and subaltern studies. Like many great thinkers, he remained persistently

marked by alienation and exile, while maintaining an unwavering commitment to human rights wherever they were violated.

Throughout his lifetime, Edward Said meticulously examined the complex interconnections between power, culture, and knowledge. He elaborated on the condition of exile as a profound existential experience, marked by displacement, loss, and a persistent sense of otherness under often unforeseen circumstances. This condition significantly shaped Said’s critical engagement with writers who themselves lived in exile or outside their homelands, particularly figures such as the English-Polish novelist Joseph Conrad, German critic Eric Auerbach, British writer T.E Lawrence and the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. In Said’s discourse, exile occupies a central place, positioning him among the most sensitive and perceptive intellectuals of his time—an insight he articulated eloquently through his wide-ranging interdisciplinary writings.

For Edward Said, the Palestinian narrative was never confined to slogans or rhetorical claims; rather, it constituted a concrete and courageous intellectual defense. The symbolic framework of Palestine that he constructed remains an indispensable reference through which the Palestinian issue and identity continue to be defined and

remembered. Said’s enduring legacy demonstrates the importance of principled intellectual commitment in ensuring that a cause is not only voiced, but also heard,

recognized, and taken seriously.

One enduring lesson is that Palestinians in the diaspora have carried their stolen land, people, and collective memories not merely as nostalgic sentiment, but as a sustained

and realistic vision actively maintained with the hope of eventual restoration. This vision is embodied in the right of return, a principle deeply inscribed in Palestinian collective memory wherever Palestinians may live in exile. This powerful claim was articulated with exceptional intellectual clarity by one of the greatest critical minds of the twentieth century, Edward Said.

Nassir al-Sayeid al-Nour

January 2026

Nassir al-Sayeid al-Nour is a Sudanese critic, translator and author.