Run my dear, from anything that may not strengthen your precious budding wings. Run like hell my dear, from anyone likely to put a sharp knife into the sacred, tender vision of your beautiful heart.

— Hafez

As an Arab sci-fi author, activist and journalist I’ve been ‘observing,’ and for quite some time now, the slow but steady development of science fiction written by Arabic women authors. My observations have been up close and personal in the case of Egypt, where I live and where I’m a member of both the Egyptian Society for Science Fiction (ESSF) and Egyptian Writers’ Union. Previously, I’d argued that women were very well represented in the other genre fields, fantasy and horror, but were still playing catch-up in science fiction. There is in fact a goodly number of female science fiction authors in Egypt, but they are mostly present in short fiction, and there thankfully isn’t any discrimination against them in this field. (Not more than anybody else, given the clear bias ‘against’ science fiction in Arabic literature).1

Then it finally happened. The bow broke on the swirling whirlpool of talent out there, evidenced by the plethora of novellas and full length novels by female authors at this year’s Cairo International Book Fair. (The resistance to science fiction is also on decline, evidenced further with the range of science fiction subgenres on display, along with fantastical book covers, at the 2026 book fair). I bumped into some of these authors at the fair, and they’re generally of the younger generation. Fresh out of college or still at college, and chaperoned by their mothers at the fair!

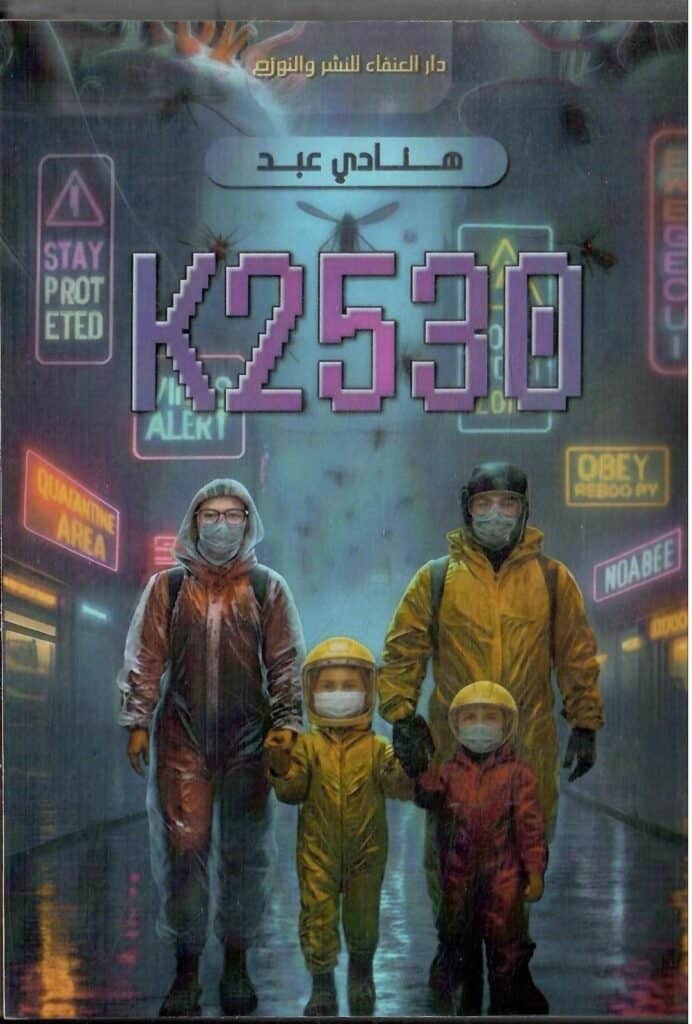

Another surprise at the fair was chancing upon a science fiction novel by a Palestinian female author, Hanadi Abd, and from Gaza no less. There are plenty of female Palestinian authors around in the diaspora writing in English but this writer wrote her first science fiction novel (ساعة زمن) in Gaza in 2019, making it the first novel of its kind written in Arabic by a Palestinian woman. Weirder still her next novel, which she began writing that same year, centers on a plague that breaks out in an imaginary Arab country in the year 2030, the result of the folly of ‘man.’ The story, K-2530 (2020), also has a cabal of corporate hacks secretly taking advantage of the outbreak to their own global benefit. That’s almost, to a word, what happened with Covid, and the novel saw it all coming. Even weirder than that, the cure for the potential pandemic lies in the veins of a poor, orphaned boy found out on the streets, covered in scratches and bruises – as if in anticipation of the cataclysm that would befall Gaza (and its children) in 2023.

There’s nothing quite like feminine intuition when it’s applied to future history. But, more to the point, writing on this topic poses the question of what is unique and distinct about women’s sci-fi in Arabic? The first thing to observe, to point out, is that science fiction written by men and women in Arabic is actually very similar – at least in Egypt. Men in the Arab world are as concerned with family and household concerns as women, and it comes out in our writing. Social drama and literary realism have been the norm for so long in modern Arabic history, and Arabic men are raised to get married and have children, and are judged on that basis by society and certainly by their parents. We can get away with a lot more as men, and have an irresponsibility streak in us a mile long, but nonetheless we are still pretty home-oriented. (A characteristic we share with Italians and other Mediterranean peoples; My Big Fat Greek Wedding might as well be an Egyptian movie). This is another plus point for Arabic science fiction since the rest of Egyptian pop culture has gone in a polarized, macho and misogynistic as well as jingoistic direction.2

Consequently there’s also no shortage of love stories and epic romances in Arabic science fiction written by men, along with the emphasis on a mother’s love as a key plot point. But women, they take it to a whole other level, with much more nuance, depth and urgency. I’ll list what I find distinctive about women’s SF at the end of this paper. But first, a summary of some of the new women’s lit I encountered at the book fair. Some other authors will be mentioned for comparative purposes.

Jannah Ismail – On the Extraterrestrial Embrace

Jannah Ismail is a very new author, first published in 2025, with three novels to date. I say novel but these works are very slim indeed, to the point that you can finish most in a single day. She’s difficult to categorize at the genre level too, skirting between the worlds of YA and children’s lit, but I’d say she’s a science fiction author at heart. Her novel The Planet of the Winged Beasts is graced with the illustration of a lion with wings, up against a lowly human astronaut in a space suit. (The sentient aliens on this planet look human and have butterfly wings, a clear allusion to angels; see below). You’re reminded straight away of griffins and other fairytale beasts, but nonetheless when you read an older novel,The Missing Part, it seems at first to be a ghost story with a boy and girl seeing each other in spectral form while both at the same graveyard. But while they’re in this spectral world, they chance on two old timers, Mr.s Ibrahim and Isaac, and the old timers look through their bookshelves to find that the two potential sweethearts are actually from another dimension.

In Winged Beast the erstwhile hero of the story, Mustafa, works in an observatory and is full of ambition and energy after they find a new planet. He intends to go there, alone, to get all the accolades, building a spaceship literally out of spare parts he purchased from a junkyard. Nonetheless, you can’t help but notice that he’s introduced to us primarily through the eyes of his dutiful sister Mariam. He’s more than a brother to her, since their parents died in a plane crash while heading off to Saudi Arabia for pilgrimage. And she’s practically a housewife herself, studying hard and doing ‘all’ of the household chores so he can focus on his mission in life. He goes to this far-off planet, which should take him 500 years given the distance, in five mere days. He finds a planet teaming with life and with breathable air, with the residents conveniently speaking Egyptian Arabic. He meets the king, Yaraqa (Larva), and he introduces the boy to his daughter Asifa (Storm) while explaining that the elite on this planet have special abilities, such as making storms. Mustafa is then invited to the royal palace, a magnificent building made out of blue diamond. He’s given a room with an electronic bed that’s designed for people with wings and then meets Storm’s tempestuous baby sister, Yaqoot (Ruby), who can disappear and make diamonds.

Mustafa is impressed with the planet. The people are peaceful and advanced and well off, although they are attacked from time to time by other humanoids from offworld, riding horse-like animals. (The residents of this planet ride the winged lions since their own wings can’t handle reentry and cosmic rays). Then something suspicious happens. The king tells Mustafa his spaceship is in the basement of the palace, but he won’t let his daughter go with him down there. He goes off to the basement but lingers outside and overhears the king talking to Storm about what he plans to do to Mustafa; he wants to remove his brain. They’ve become suspicious of outworlders thanks to the repeated attacks and need their help to fight back, which is why they have a collection of stolen brains.

Storm pleads with her father to no avail, saying she’s fallen in love with him from first sight, despite her father’s position on foreign marriages. She eventually confesses to Mustafa, professing her love and giving him a bracelet – a plastic tube with her blood in it. It’s the custom on their planet and he pretends to be surprised. He tricks her into his ship and traps her in a prison cell to head back to earth and become world famous. (Ruby agrees with her father and stows away in secret, but she gets captured as well). Mariam berates him for what he’s done while Storm begs him to let her go. He explains to Mariam, quite nonchalantly I might add, that Storm ‘loves’ him but she’s not human, so he clearly can’t marry her. In the meantime, his long distant uncle comes visiting, obviously bringing his son for Mariam, forcing Mustafa to hide his captives and the ship. (I won’t tell you how). Eventually he wises up and lets them go and promises to bring them back home, apologizing to Storm that he can’t marry her. Society won’t let him, and he’s not worthy anyway.

The story closes years in the future after he’s older and married. His little girl is named Storm and his wife Malak (means angel). He finally explains to the girl why he gave her that name. Meanwhile his wife is on the phone, ignoring him. This may seem cheesy but it’s actually very intelligent. Mustafa and Mariam are very religious names in Islam, associated with the Prophet Muhammad and the Virgin Mary, while this so-called hero clearly missed the opportunity of a lifetime to find true love with someone who is clearly of an angelic disposition – with wings to boot. He substitutes with a human girl with an angelic name, but she’s not nearly made of the same considerate and pristine stuff. As for his excesses, he’s obviously a bit spoilt, given his sister doing everything for him while he lazes away dreaming of his mark in the history books. His boss at the observatory is also portrayed like a wise old man.

Not coincidentally the observatory is built next to the pyramids of Giza, celebrating Egypt’s great history, with the institution itself build on the shape of a pyramid. The ‘fourth’ pyramid, it’s called. This imagery is unmistakable if you’re familiar with Egyptian science fiction and the symbolism of national unity. Ancient Egypt is the umbrella under which all the different cultural and religious contributions to Egypt reside, not least Islam and Christianity.3 Hence, Mustafa and Mariam. You see hints of this in Missing Part, with Mr Ibrahim (Muslim sounding) and Mr Isaac (Ishaak in Arabic) which is Jewish sounding. Arabs are the sons of Ishmail, after all, and the old-age duo comments on the excessively differentiated religious places of these human interlopers compared to this spectral world.

Egypt is the melting pot, as I’ve argued elsewhere, and our science fiction writers are positively eager to find life out there and often see it as more advanced – morally and not just technologically. They constantly find common ground with space aliens, even at the level of religion, and this is a predisposition our religious scholars, theologians and jurists had in the past.4 The same holds here, with journeys outwards really being allegorical journeys inwards. Hence the spectral world in her other novel, which is a form of benign escapism. The girl character is from a poor family and beaten by her father, journeying to her mother’s grave, while the rich boy is neglected by his own family, also going to visit his deceased grandmother. When they meet their respective families in this parallel world, they find them actually behaving themselves. A focal point in this netherworld is the sea, which is coloured purple, with a glass wall on the coastline. It’s the place where the young duo lose their restraint; she pushes him in then jumps in herself, with their clothes on of course. You almost feel it’s a reference to the river Nile, another symbol of national unity, a pairing of opposites.

The glass wall, which is so wide you can walk on, is a Quranic reference. The Prophet Solomon built his palace over water, with a crystal floor. (See below). The city they now reside in is populated with flower gardens and wide open spaces, our image of paradise as Muslims. And certainly our deep-seated desire as Egyptians, given how crowded, dusty and dry Cairo is. (I’d also wager the stolen minds is a reference to the ‘brain drain’ in Egypt, with our best minds going abroad). But that’s enough of the Egyptian imagination. Let’s see what Palestinians have to say.

Hanadi Abd – A Palestinian Ahead of Herself

K-2530 is a prophetic novel, and in more than one way. It begins with an idyllic scene that is almost too good to be true. A wife is busily cooking a sumptuous meal for her son, who is playing out in the garden with his smart toys – something like robot teddy bears who do educational instruction. She has a robot cook to help her and the sun is shining outside, and she also has a mechanical dog whose job is to monitor the boy and keep him safe from sharp edges while also taking the boy’s biometrics. The narrative voice tells us this portends badly and the mother hears her boy screaming. Turns out he’s been stung by a flying insect. She goes out and gets stung herself. She shuts down the place with a protective barrier and consults an online AI health expert for advice. Her husband, Iyad, comes homes later and they have a lovely meal – his wife has smart clothes that protect her from the odor of the food. (He even gets her a present, delivered by a robot. It’s a smart blanket that will help her sleep at night; she’s been having problems lately). But she develops a fever and their boy gets ill. He rushes them to the hospital but their condition continues to worsen, finding the hospital itself is overloaded with similar cases. In the meantime we are introduced to a Dr. Adnan and his own story arc. He’s a brilliant young scientist and went into medicine after his mother died from a fatal insect bite in the tropics. This put his original marriage plans on hold, courting a librarian, and he keeps returning to this forlorn sweetheart to prove himself to her. He tries to develop a cure to the disease that killed his mother, injecting the virus into flying insects, only for them to escape and spread a much more lethal version of the disease. Naturally, he doesn’t own up to this, and then he gets kidnapped by a mysterious cult of individuals who dress in black with the icon of an owl on their outfits. (The owl is a bad omen in Arabic culture, not a symbol of wisdom as in European culture).

Iyad now loses his wife and only child and returns to his home, defeated. He even gets rid of a lot of the machinery and eats out most of the time. He has to wear a rubber suit with a helmet to avoid being stung, just as everybody else. (A new electroshock system is also developed to kill the insects). He then finds a little boy out in the streets, as mentioned above, and takes him to a hospital. He hands the boy over to a new character, Dr. Faten, and she does tests and finds he is infected but the disease isn’t spreading. He’s developed antibodies. The doctor is Dr. Adnan’s assistant. That’s when Dr. Adnan interjects, has the boy transferred to a secret laboratory of his own, and threatens to kill Dr. Faten if she tells anyone.

Iyad has nightmares about the nameless boy, feeling he has abandoned him, not even asking the boy’s name. He checks on him and Dr. Faten tells him the boy is dead, as she’s been told, but he doesn’t buy it. He investigates, finding a way in, and is helped by a journalist who is later killed by the secret society, apparently a pharma corporation with grander plans for the world. Dr. Faten confronts Dr. Adnan and is almost killed by him. Iyad rescues her and gets her the cure, a vile labeled K-2530 and they use a live TV transmission to expose the good doctor – the colleague of the slain journalist helps them, a woman of course. The cure is mass produced and Dr. Adnan exposed to be profiting from the pandemic, since he has shares in the companies making the rubber suits and the electroshock killer.

Needless to say Iyad and Faten later marry and adopt the boy. The big loser here is the librarian love story of Dr. Adnan, shocked to see the news and refusing to believe it if not mount a defence for her man. (She was also angry at his mother for postponing the marriage indefinitely). Cheesy, I know, but then again, so was the work of Jannah Ismail. We can see the Palestinian notion of the good life here, with a garden and excellent education and open spaces – sunlight and air. But the real good life is family, and a responsible, caring and gentle husband. (Iyad and Adnan are very generic Palestinian names, incidentally. Faten means alluring in Arabic; the doctor wears contact lenses that change colour). The technology is nice, no doubt, but really a sideshow to the main attraction. Why else would Iyad dump most of the machines after his wife dies? And the author, from the preface onwards, warns about the arrogance of ‘men’ (not just human beings) in not respecting the natural balance. Being cooped up after the outbreak is the opposite extreme. Hence also the little hints that something is wrong, such as the wife’s problems sleeping – as if portending something bad is around the corner.

Dr. Adnan isn’t that different than Mustafa in Winged Beasts, to be honest. He was probably an only child himself while his mother was busy pursuing her global career, neglecting the home front so to speak. There’s no brain drain in this novel but nonetheless you do feel this imaginary Arabic country is meant to highlight how we can all benefit technically and materially if we keep our productive minds at home. Why else would you have a foreign cabal kidnapping a brilliant scientist? (Why else would the scientist himself be egotistical and make money on the side if all scientists got the respect they deserved in Arabic countries?)

The library is an allusion to the wisdom of ages, with a woman caretaker no less – almost a mother figure in her own right, like Dr. Faten. (Recollect Mariam from above?) The female characters here aren’t the heroes, or villains, but nonetheless they are proactive and in more than one way. The author clearly sees that woman have to bring up boys to be men, to be responsible and take the initiative; Iyad’s dream about the orphaned boy. Now to blend the Egyptian and Palestinian, which are already crosscutting before our eyes.

In Conclusion

From a masculine perspective, including that of my own, three things distinguish science fiction written by Arabic women compared to Arabic men. The first, of course, is the emphasis on drama, romance and family settings if not family feuds. As said above, male writers like to talk about these things too, to the point of shedding tears on happy or tragic occasions – myself included.5 Nonetheless, you feel these are just plot points meant to drive the story forward, in our unadapted hands. When you read women’s lit, it’s the real thing. With women authors, they’re using the sci-fi worlds they create to put the spotlight on the family, and with that the ‘prescribed’ roles of men and women. To be fair, the women in the above listed stories aren’t the heroes of the respective novels, but this is not a copout on the part of the authors. From speaking to an epic fantasy author, Asmaa Kadry, she explained that woman authors often like to have the protagonist be a man since it forces them as women to write from a male perspective, a challenge they eagerly welcome.

The works referenced above are also strictly speaking multi-perspective novels. They are written in the third-person and individual chapters tend to be looked at and driven by a specific character, male or female. That is certainly the case with K-2530 and Missing Part, with the female character in Missing Part doing most of the talking.

There are plenty of proactive female characters if not protagonists in other stories I have read but the commonality you find across the board is the emphasis on men having to live up to their designated roles as providers and protectors. Gentle, sweet and loving fathers and husbands and fiancés, no doubt, but responsible men who have to put their loved ones ahead of their careers and egos. With some tongue-in-cheek criticisms of women who let them get away with being self-centered. Sadly, I am not an expert on women’s lit but these moral considerations do seem to be a feature. The first time I came across it was in the novel Little and Good (1940) by Ruby M. Ayres, with similar vibes in the award-winning Belgian movie Young Mothers (2025). That movie has a series of jerks disowning their girlfriends and subsequent babies, except for one guy who is a good boy who is eager to be responsible. Not coincidentally, he has lots of support from the women in his family.

The second distinguishing characteristic of Arab woman’s science fiction is narrative innovation. This is another field that Arab women authors are way ahead of us men, at least in science fiction. We’re very wedded to the linear format of the novel or short story as Arabic men, for some reason. That doesn’t mean we don’t ever experiment or do things differently, with flashbacks or narrative leaps, but it feels forced on our part. With our female counterparts it is almost second nature. I found this out the hard way whilst reading The Result of a Change (2018) by Eman Nabil, an expatriate Egyptian living and publishing in Saudi Arabia, and in English no less. Straight away, I drew a comparison with the TV series Station Eleven (2021-2022), also adapted from a work of woman’s sci-fi; Emily St. John Mandel’s 2014 novel. Both works retrace themselves, going over the same events but from the differing perspectives of the various key characters. Eman’s novel is written in the first-person and single-fatherhood is a concern in Station Eleven too.

A novel I’d acquired from the previous installment of the Cairo International Book Fair, A Sheikh on Mars (شيخ على المريخ, 2025) by Hanan Al-Housini, is in the third-person true enough but keeps slipping from present to past throughout the text – even in individual chapters. The protagonist this time around is a woman, stranded without a memory on the red planet, but her male second half shows up shortly afterwards and suffering from the same problems. Flashbacks are either told from an all-seeing perspective to help fill in blanks or from the perspective of the various characters, to help them grow and face up to their memories. An even more innovative novel is We Were Created for the Dark (خلقنا للظلام, 2022) by Asmaa El-Yamany. The heroine of the story, Serine, is an investigative journalist in the present-day world doing some research on the side about an ancient Babylonian princess, Talin, only to see this woman in her waking hours and fuse with her and travel back in time. In reality, she’s just remembering, being this immortal princess, with adventures ensuing involving vampires and werewolves in the past and present; sometimes literally, sometimes metaphorically.

These modes of narrative ‘folding’ connect to the first point of distinction of Arab women’s science fiction, since it forces characters to confront themselves – male and female. Consequently, both storytelling and world-building in woman’s science fiction is morally driven. Another older novel I’d reviewed before, Sandra Serage’s What If (2023), is another example since the protagonist in it, Shams (or Sun), finds a way to travel through wormholes to an alternate or parallel reality. While there he meets himself and is not impressed, since his alternate self made some wrong decisions in his life that seemed rational at the time. Then both are confronted with a third version of themselves who found his own way from his world. They fight and bicker only for Shams to wake up. He’d been conducting an experiment involving a dream machine that gave him three versions of himself based on his subconscious – the ID, Ego and Superego. Needless to say, he goes home to a wife and happy home, content that he made the right decisions after all in his life and isn’t missing out on anything. And he was given the romantic name Shams, by his mother, after the great Sufi mystic and poet Shams Tabrizi – fusing science with morality again, as in K-2530.

A final and praiseworthy characteristic is, how should I put it, ‘embroidery.’ Arab women authors love decorating their worlds as if they are items of jewelry or, quite literally, accessories. I say this because of A Sheikh on Mars, where the author explicitly uses the word accessories to describe the wondrous world she’s created at certain points of the story. The capital city on Mars, occupied by the eponymous Sheikh (or patriarch) is built like old Cairo, with domes and mosques and palaces, but with the central palace being made of white pearls. The palace dome is made of red pearls. And then you see a spaceship also covered in such jewelry. Earlier in the story the heroine is locked in a room in the palace of the villain and the walls and floor are made of crystal, with water traveling through them. Recollect Missing Part from above, in reference to the Prophet Solomon, and also the blue diamond palace in Winged Beasts? Not to forget the aptly named Ruby. As for Hanadi Abd, she decorates her characters. Iyad is broad-shouldered and handsome, with strong but sensitive eyes while Faten has her contact lenses. Iyad’s original wife has nutmeg-coloured eyes that match her brown hair and artificially enhanced rosy cheeks, while another woman character has almond-shaped eyes, etc.6 (The first alternate world Shams travels to in What If is a romantic haven, with a larger moon and spaghetti sauce that is purple; red is too ‘violent’). All these colours, they stand out at you.

Jannah Ismail’s Missing Part also relies on colour to communicate meaning. The colour of the sky and sun matches twilight in our world and the gardens are full of brightly coloured butterflies. More significant still are the flowers, all of whom are blood red, expect for one which is white. The boy plucks it and gives it to the girl, and magically the flower never withers. When he plays a guitar later on, it opens up. It’s a clear indicator of her – the unique one among the multitude that needs someone to recognize her to fully bloom.

My goodness, science fiction written by Arabic men is bland by comparison. We’re either too utilitarian and describe hardly anything in our stories, or populate our worlds with grim grey or beige constructions full of urban decay. I exaggerate of course, but there’s something to be said here about narrative borrowings and genre blending. Female authors are much more comfortable borrowing from fantasy motifs and storylines than us guys, which explains the opulence and decorations. The only colourful male equivalents I can think of are Dr. Hosam Elzembely’s novel The Half-Humans (2001), which has a noble King in opulent robes and a magnificent palace on the Planet of the Seven Hills, and Ammar Al-Masry’s Atlantis novels. They’re loudly coloured and explicitly reference Tolkien while borrowing heavily from both Arabic fairytale traditions and Japanese computer games. The rest of us are either content to have a squeaky clean chrome-lined future or a post-apocalyptic reset of civilization backwards to dusty chaos and collapse. Again I exaggerate but it is a problem for us ‘hard’ science fiction writers, and both Dr. Hosam and Ammar are avowed fans of The 1001 Nights.

It could be that girls gravitate even more to the fantasy worlds of yonder, finding them more relatable and attractive, or they are more attuned to colour and fashion than us men ever will be. I’ll let the readers fill in my blanks. Almost all of the science fiction I read, in English, is by men – to my dying shame. This brings me to my final observation which is that Arabic woman science fiction authors are filling key gaps in our literature, once and for all. Emotion, drama and social settings are a bit lacking in Western science fiction in general, written predominantly by men. It can’t be a coincidence that the first ever science fiction novel was about a family setting with a tragic ending. I mean, of course, Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein, with Victor as the wayward father who usurps the creationary role of woman. Did I mention that Dr. Adnan is explicitly called the mad scientist by the end of Hanadi Abd’s novel? And he was driven much like Doctor Frankenstein, by his inability to handle personal loss and so his desire to defy the laws of nature, if not the ultimate creator, God himself.

Sadly, another non coincidence is that Mary Shelly was obscured with time as men took over this fledgling genre from Jules Verne and H.G. Wells onwards. Novels and stories like those cited above are finally redressing the balance, at least in our part of the world. I said above the bow has broken. It could very well be the first sign of a deluge of female science fiction authors. Dudes beware!

Emad El-Din Aysha, PhD

February 2026

Footnotes

- Please see my now terribly outdated article “Egypt as a Test Case for Gender in Arabic Science Fiction”, SFRA Review, Vol. 51, No. 1, Winter 2021, https://sfrareview.org/2021/02/07/egypt-as-a-test-case-for-gender-in-arabic-science-fiction/?fbclid=IwAR3xLVfTiWB0GLF8wZDgGmjpmXC6Pn-EVe-DZmV86lhI4lS4QAcsv7qzYYM. ↩︎

- This was the overwhelming conclusion of the conference “Mainstreaming the Margins & Marginalizing the Mainstream in Contemporary Egyptian Culture”, held at the American University in Cairo but organized by CEDEJ (26-28 October 2025). Thank heavens Egyptian SF bucks the trend. Please see my chapter contribution “I’s & Others in Egyptian SF: Difference and Tolerance in the Alien Mirror”, Identity and the Dynamics of Border Crossing (2026), edited by Saad Boulahnane, IGI Global Scientific Publishing, pp. 315-338. ↩︎

- Please see my chapter in Islamic Theology and Extraterrestrial Life: New Frontiers in Science and Religion (I.B. Tauris, 2024), edited by Jörg Matthias Determann and Shoaib Ahmed Malik, pp. 205-230. ↩︎

- Here’s my subsequent review of the book – “Hotels in Heaven”, The Liberum, 16 January 2026, https://theliberum.com/hotels-in-heaven-reviewing-islamic-theology-and-extraterrestrial-life/. ↩︎

- Jörg Matthias Determann, “Emad El-Din Aysha on ‘Arab and Muslim Science Fiction’: ‘Our male heroes aren’t criticized for crying’”, Arabic Literature in English, 31 May 2022, https://arablit.org/2022/05/31/emad-el-din-aysha-on-arab-and-muslim-science-fiction-our-male-heroes-arent-criticized-for-crying/. ↩︎

- A small side note here. I got berated once for not describing my male protagonist while describing his love interest in excruciating detail. The editor, needless to say, was a woman. And her criticisms were well placed! ↩︎

Emad El-Din Aysha is an academic researcher, sci-fi author and freelance translator and journalist currently residing in Cairo, Egypt. He was born in the UK in 1974 to a Palestinian father and Egyptian mother, completed his PhD in International Studies in 2001 at the University of Sheffield and has taught at universities as diverse as the American University in Cairo and Heliopolis University for Sustainable Development. He has a regular SFF review column in The Liberum online newspaper and formerly wrote for Egypt Oil & Gas and The Egyptian Gazette. He has two books to his name, the nonfiction ‘Arab and Muslim Science Fiction: Critical Essays‘ (McFarland, 2022), and an anthology in Arabic that has recently been republished – ‘The Digital Hydra’ (2026) – see below. He also had the honour of publishing a story with the first ever anthology of Palestinian SF (Palestine+100) and the award winning Thyme Travellers, and is a member of the Egyptian Society for Science Fiction regularly represents Arab literature at forums like Balticon and WorldCon.

Special thanks to Gloria McMillan and the Tucson Hard-Science SF Channel.